From 1985: Stand up, mayor

Thirty-six houses on fire, and this small, silly, expedient man ... says he takes full responsibility, as if he were somehow big enough to make what was happening in West Philadelphia all right.

This story was originally published on May 14, 1985.

The man on television just said there were 36 houses on fire. Thirty-six houses.

A few minutes ago, at the mayor’s press conference, a reporter asked Wilson Goode what the rest of the country will be saying about Philadelphia tomorrow. The reporter was concerned that the city’s reputation was damaged, now that it had responded to a neighborhood’s problem by burning down the neighborhood.

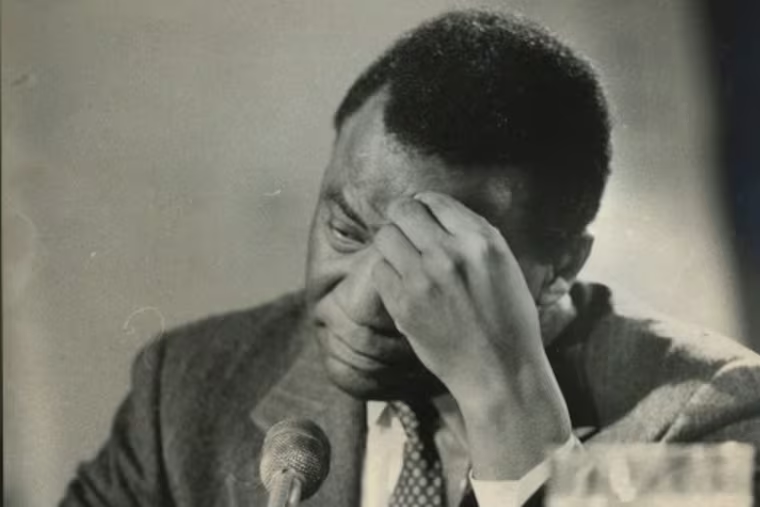

It was the last question Wilson Goode answered before he left the podium, and he made it count. He said the rest of the country would be saying that the city wasn’t afraid to deal with its problem. He said the rest of the country would be saying that Philadelphia had a “stand-up mayor,” who was not afraid to take responsibility for the actions of his subordinates.

Thirty-six houses on fire, and this small, silly, expedient man; this politician who has been standing in the shallow end of the pool so long that people never noticed he couldn’t swim, leans into the microphones at City Hall and says he takes full responsibility, as if he were somehow big enough to make what was happening in West Philadelphia all right.

Go tell them that on Osage Avenue, Mr. Goode.

Go tell them on Pine Street. Tell the people who worked for those houses, who paid city taxes, who grew flowers on the wood gratings of their porches.

Tell the cops sitting on the horses in Cobbs Creek Park, or the firemen in the street fighting this thing. Tell them you take responsibility for dropping a satchel bomb in a part of the city where people care about their houses and about each other, but didn’t think far enough ahead to figure out a way to put out the fire.

The mayor, of course, will not tell them anything on Osage Avenue. He won’t go near that street, or the people who used to live there.

In this, he is consistent. He has ignored them, and their problems with MOVE, for over a year. He would still be ignoring them tonight, except last month the people of Osage Avenue decided they had been ignored enough.

They decided they were tired of calling the police and the mayor’s office and License and Inspections and getting no help. They were tired of complaining about beatings and bullhorns and odor and obscenity, and being ignored.

And so they complained to somebody else.

They went to the papers and the television stations. They called a press conference and laid out what MOVE had done to them and the 6200 block of Osage Avenue. They described the way they had been forced to live, and they said either the city could do something about it or they would.

And that worked, where nothing else would. It is the one thing that does work with Wilson Goode - when so many people see something that he can’t ignore it.

In the next few days, of course, Wilson Goode is going to tell you that he was unaware of the seriousness of the problem. He has, as a matter of fact, already started minimizing the number of complaints his office got. He will probably deny that the police have been operating under a different set of orders when dealing with MOVE than they were for everybody else. He will deny he knew the extent to which MOVE was armed.

And if he says those things, he will be lying.

He will probably say that as soon as he became aware of them, he acted.

And if he says that, he will be lying again. He acted after the people who live on Osage Avenue called a press conference, and by then the physical problems of confronting MOVE were incalculably more difficult.

I stood in Cobbs Creek Park half of yesterday afternoon, then I walked up and down the streets that border Osage and Pine. The police had barricaded off any direct view of the MOVE house, but pieces of roof floated up off of it with the smoke, and blew over the neighborhood.

The smoke alternated gray and black, and the black carried some of the spray from the hoses a few hundred feet, and then dropped it like rain on the sidewalk. Children stood on porches, drinking Kool-Aid out of baby bottles.

Then the fire grew, and the pieces floated up from other houses in the block, and then it was 20 and 30 feet over the roofs, and the mothers brought their children inside.

Earlier in the afternoon, it occurred to me that I wanted to understand MOVE’s principle in this. That if a half a dozen adults were going to die in a war with the city of Philadelphia, you had to take the reasons seriously. That somebody ought to know why.

That has always been the trouble with MOVE - the principles are everything, and nothing. It is willing to fight a war with a city, and let the reasons - assuming there are reasons - die as obscure as the members themselves.

By the time the fire had taken most of the block, though, it was not MOVE I was wondering about.

I was thinking about the city, and what its reasons could have been.

What its explanations would be.

And later Wilson Goode would hold a press conference and say the city had not been afraid to deal with its problem, and that he was a stand-up mayor.

And the number of houses would keep going up - it’s 60 as I finish this.

And there are three dead men in the MOVE house, I don’t know how many babies, or what the final numbers will look like.

What I know right now is that this isn’t the day to be looking for reasons.

This story was originally published on May 14, 1985