Philly’s Acori Honzo couldn’t find figurines of Black folks, so he started sculpting them

Cherry Street Pier artist Acori Honzo has created dozens of figurines of Black leaders like Malcolm X, Whoopi Goldberg, The Notorious B.I.G., and Marvin Gaye.

Shortly after the 2008 death of actor Heath Ledger, Philadelphia artist Acori Honzo studied the intricate details of a 12-inch figurine of Ledger’s Joker character from The Dark Knight. His wife had purchased the figurine while shopping at Comic Universe in Delaware County.

Inspired, Honzo decided to start collecting figurines. He wanted to include Black characters and celebrities in his collection, but when he searched for them, he couldn’t find any. So he bought sculpting supplies to create his own.

While working an administrative job, “I just started sculpting at my desk every day,” Honzo, 42, said. “As it evolved, I started to think, ‘What if we had pieces that were made based off our history?’ Everybody has had some type of toy or figurine when they were a kid. So when different generations see these pieces, they can connect. It also sparks a conversation about our race, our history, and our imagery.”

He has gone on to create figurines of dozens of noteworthy Black folks, from Maya Angelou and Jean-Michel Basquiat to Whoopi Goldberg and the Notorious B.I.G. Honzo was already a painter and graphic designer, but it is this sculpting work that now defines his artistic practice. Honzo’s figurines are considered artworks and cost at least $1,600. Each figurine is handmade and takes several months to complete.

Figurines are scattered on the shelves of his Old City studio: Angelou, wearing a floor-length kente print skirt; James Baldwin, clutching a cigarette between his lips; Basquiat in paint-spattered clothing. Some are a part of his personal collection, others are commissioned pieces.

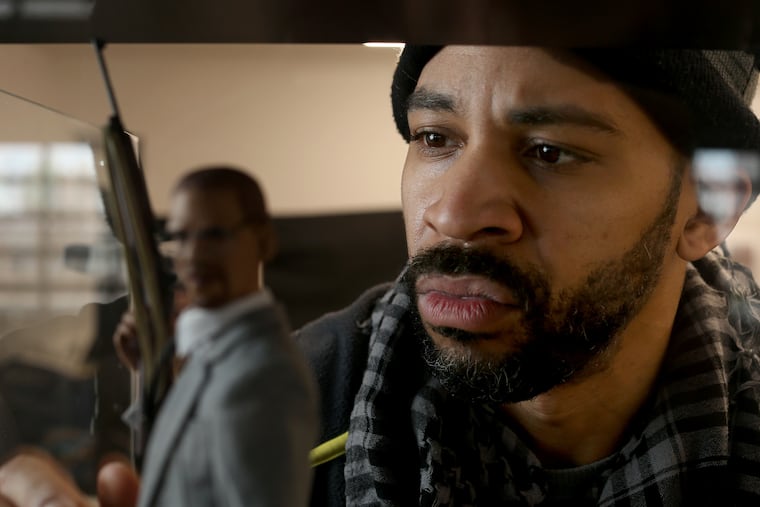

Here, too, are a suited Malcolm X holding a shotgun, Marvin Gaye dressed in a fur-collared coat and holding a microphone, and Jerome from the ’90s sitcom Martin, with his signature roller-set hair.

“I make what I think is cool, and people just buy what they like,” Honzo said.

The figurines are sculpted from polymer and oven-baked clay and then cast in a plastic resin, which prevents the figure from shattering and allows more malleability. To sculpt the facial expressions — furrowed brows, smile lines, and dimples — Honzo uses dental tools.

“There’s so much relatability to Acori’s work,” said Chezarea Brooks, who has known Honzo for over 20 years. “When we look at a rapper that Acori has done, we remember where we were in life when we first heard that song.”

The figurines are all hand-painted by Honzo. The clothes are hand-sewn by Honzo, his wife, and tailors based in Spain and China.

Honzo’s figurines were first exhibited at Moody Jones Art Gallery in Glenside in 2017. “The guy that owns the gallery was the first person to tell me that these [figurines] were pieces of art and that they should be in a gallery,” he said.

In 2018, Honzo was one of 12 artists to be selected for the Cherry Street Pier’s first residency program, which offers the artists subsidized studio space and marketing support for one year. Honzo’s residency was renewed in 2019, making him a member of the second cohort, which will have their terms extended because of coronavirus closures. Last year, prior to the coronavirus crisis, he held an exhibition, This is Our Story, at the pier, which is now open weekends only (noon to 8 p.m. Friday through Sunday).

“Acori’s work manages to make this really powerful statement, but still feels easy and comforting,” said Sarah Eberle, Cherry Street Pier’s general manager. “Everyone that walks by his studio just loves his work. Little ladies go in and love his work. André 3000 goes in and loves his work. [Honzo] creates really comfortable spaces to have difficult conversations.”

At any given moment, Honzo says he’s working on four or more figurines, most of which are commissioned. “It’s like I’m being whispered in my ear to work on this specific thing at this specific time,” Honzo said. “It’s like organized chaos. I’ll work on this one’s hair, jump and do this eye, jump and sculpt this nose. I just go with what I’m being told and let God guide my hand.”

Honzo has always had an artistic mind, a trait he said he inherited from his father. When he asked his father to teach him how to draw, his father drew a stick figure and instructed him to fill in the musculature. Honzo furthered his understanding of illustrating anatomy by studying comic book characters.

During the early stages of the coronavirus pandemic, Honzo didn’t have access to his studio, but the closures didn’t delay his production. He set a goal to make 15 head sculpts by the time his studio was scheduled to reopen, roughly three months.

“I took that time to evolve and hone in on my craft,” Honzo said. “I did all that work and when we reopened, I hit the ground running. And I had much more clarity in my vision and my purpose, making sure I knew how to execute it.”

Now that his tailoring skills have improved, Honzo wants to make more figurines of Black women. His latest project features figurines that depict the four little girls who died in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., in 1963. He’s also working on an Angela Davis piece.

“I just want to have my work seen by my people,” Honzo said. “I want to present my work in a way that uplifts and gives you a feeling of nostalgia without trauma.”