Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater opens its first tour in 2 years at the Academy of Music

“I think it’s very fitting [to open in Philadelphia] — and very close to New York,” the company’s home, said artistic director Robert Battle. “So that’s nice as a beginning."

On a snowy Friday night, the Academy of Music was mostly full for the opening of Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater.

It was not just a Philly opening but the launch of the company’s 2022 national tour as well as just its second set of live performances since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“I think it’s very fitting [to open in Philadelphia] — and very close to New York,” the company’s home, said artistic director Robert Battle by phone earlier that day. “So that’s nice as a beginning, you know, to not be on an airplane.”

It was fitting because both the company and Battle have many Philadelphia ties. Battle studied at Juilliard under Jeanne Ruddy, who owns the Performance Garage. He was awarded an honorary doctorate from the University of the Arts in 2014.

Several company dancers have performed with Philadanco, including Jermaine Terry, Jeroboam Bozeman, and Michael Jackson Jr. Another dancer, Kanji Segawa, has done a lot of choreography for the Metropolitan Ballet Academy in Jenkintown.

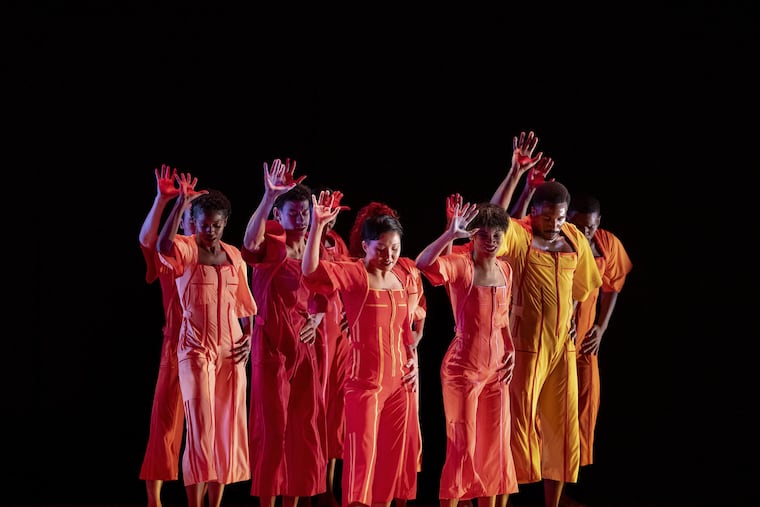

Friday’s opening program (which alternates with a second series of dances at the Academy) was a tasting menu of eight pieces, including many solos and duets, ending with its signature Revelations, which is practically required viewing when Ailey comes to town.

The program had fewer fireworks than many Ailey programs, but it was a delightful mix of all the company can do, all choreographed by Battle except for Ailey’s Revelations.

The company is smaller now, too. A number of dancers, including Hope Boykin, who previously danced with Philadanco and is now a choreographer, retired in early 2020, and the company did not replace them. It also furloughed all of the dancers in Ailey 2. Hiring has restarted again.

The newest work on this weekend’s program was For Four, which premiered in December in New York. It is something of a pandemic piece, in that Battle started working on it in early 2021, when dancers were just beginning to step out. At first, he had planned a solo but then wound up using four dancers who had been working in a cohort.

It was a breakout piece for Battle, too, who decided to step beyond his comfort zone for this piece set to music by Wynton Marsalis, since it was only meant to be shown once during a virtual benefit for the company.

“I’m not terribly jazzy in my choreographic nature,” Battle said. But thinking a single virtual viewing was a safe space, he decided, “I’m just going to do stuff that I normally wouldn’t do in terms of some of the movement choices. And so I think that kind of freed me up.”

The four dancers, however, would not touch.

“I’m not huge on partnering anyway,” Battle said. “Just the thing is that lifts make me crazy. I’m a nervous nelly. I’m like, ‘Oh my god put her down.’ It’s very funny. I’ve always been this way.”

As pandemic pieces go, For Four is an optimistic one, showing there is still joy to be found. That is a relief, considering how much recent work has been made about isolation and fear.

But if you know where to look in this short piece, there is a bit of that, too. At one point, a dancer falls to the floor, with a flag projected behind her. In the virtual version, Battle said, the red of the flag draped over the dancer looked like blood.

“I grew up as a Boy Scout,” Battle said. “You know, that symbolism? We said the Pledge of Allegiance and we looked at the flag. And to see the ways in which the flag has taken on different meanings for different people, who use it as a sort of weapon to say that their nationalism means that you don’t belong.”

But it’s just a moment in time, especially on stage. If an audience member doesn’t see it that way, it’s OK, he said.

“Most people may just see it as, ‘Oh, jazz. Jazz is American. Oh, the American flag. Oh, hot dogs and, and fireworks.’ And that’s OK, too. I like that people will glean from it what they will.

“But for me personally, having been brought up in Liberty City [Miami] as a kid remembering civil unrest, remembering the shootings of unarmed black people in my neighborhood. And so when we hit these inflection moments, even though I try to suppress that to keep going, it rears its head.”

Other pieces on the program also used iconic music, including In/Side, a solo to Nina Simone, and Ella, a solo to music by Ella Fitzgerald.

Excerpt from Love Stories, set to music by Stevie Wonder, is a fun celebration of Black dance and one of three parts of a work that also has sections choreographed by artistic director emerita Judith Jamison and Rennie Harris, both from Philadelphia.

The most delightful part was where lights come down from the ceiling and the dancers turn and bow toward the back of the stage, as though the audience was really there.

Perhaps we’d all been part of this return to dance celebration the whole time.