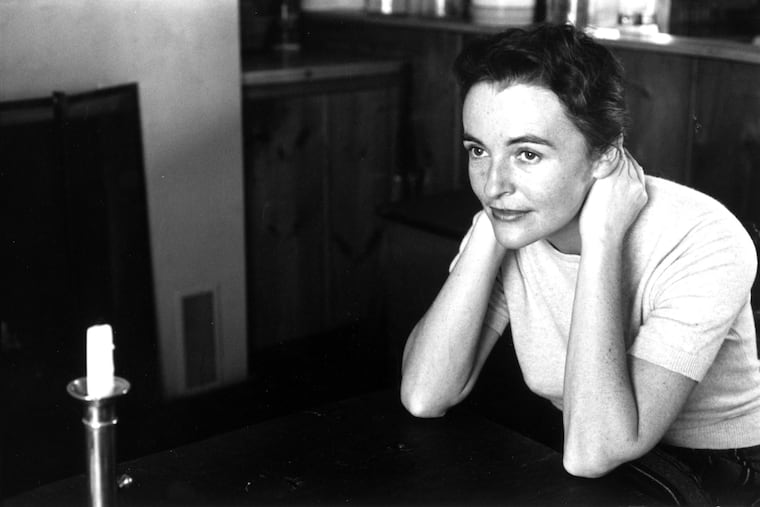

Betsy Wyeth: The woman who ‘created the worlds’ captured on canvas by her husband.

Andrew Wyeth is one of America's foremost artists who often drew the land and people of Chadds Ford, Pa. A lot of that would've remained unseen if not for his wife, Betsy Wyeth.

Only two images in the Brandywine Museum of Art’s “Home Places” exhibit of Andrew Wyeth’s paintings and drawings of local buildings include a human figure. One of them, 747 (1980), references an airplane’s slim, dissipating vapor trail.

The woman in the painting, seen from behind, is the artist’s wife, Betsy. Her left shoulder is thatched with shadows that match her raven-black hair. Wyeth evokes her soft felt hat and the seams of her barn coat. The painting’s dominant object is a home — its upper story window flung open.

The open window is in the couple’s bedroom.

This was not the first time Betsy inspired her husband’s art.

Within hours of meeting, Betsy James, then 17, drove Andrew, 22, to another “magnificent” house. The three-story clapboard belonged to Betsy’s friends — Alvaro Olson and his sister, Christina — and looked like a ship run aground. Wyeth stood on the roof of the car and painted a watercolor, demonstrating to his future wife (they married within a year) his affinity for preindustrial structures.

Wyeth later rendered Christina Olson from behind, kneeling in a field, leaning toward her home. Christina’s World (1948) is perhaps Wyeth’s most well-known piece.

“Home Places” features drawings and paintings of many houses and is the first organized exhibit of the artist’s work since Betsy Wyeth’s death in April 2020. All of the buildings, as curated by William L. Coleman, the Brandywine’s inaugural Wyeth Foundation curator, exist or existed within a “radius of just about two square miles” from where they now hang on the gallery walls.

By 1958, Betsy and Andrew Wyeth had been married for nearly 20 years, and were living in Chadds Ford, Pa., in a renovated schoolhouse owned by the artist’s parents. One day, while roaming a property close by, as her husband sketched, Betsy unearthed a “For Sale” sign “half buried by a recent flood” and purchased the place (asking her mother for help with the down payment).

According to Wyeth biographer Richard Meryman in his 1993 book, Andrew Wyeth: A Secret Life, Betsy restored Brinton’s Mill with its gristmill, granary, and a dilapidated miller’s house. She got the gristmill running with a 16-foot waterwheel. The landscape was her canvas.

The Wyeths began full-time occupancy of the property in 1963. Ten works in the Brandywine show — a fifth of the exhibition — depict this Brinton’s Mill property, including a study for Noah’s Ark and a watercolor study for Battleground. The finished Battleground — an egg tempera owned by the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Mo. — includes a portrait of George Heebner, one of the men Betsy hired to refurbish the old mill.

Brinton’s Mill also appears in two Betsy portraits: The Country (1965) and Outpost (1968). And in his much-loved work Night Sleeper (1979), featuring the slumbering family dog.

Betsy “created the worlds in which they lived,” says Maine photographer and Wyeth family friend Peter Ralston, by way of explaining Betsy’s understated yet enormous impact on her husband’s legacy.

In 1979, Betsy Wyeth hired Mary Landa to assist with her epic documentation efforts for Andrew’s paintings. The same year, she published The Stray, a novel for children, which isn’t mentioned in Betsy’s obituaries.

Published in the year Betsy’s only grandchild was born, and illustrated by her son, Jamie, The Stray is a 13-chapter story — a kind of “poor man’s Wind in the Willows,” as Ralston describes it. The book recounts a friendship between an animal-like narrator and their animal friend, a stray named Lynch. It begins the day Lynch arrives at “the Ford.”

Descriptions of the Ford are accompanied by a fictional map that bears a strong resemblance to (and can be overlaid with) the map of Chadds Ford visitors can see at “Home Places.”

Chadds Ford was, as Betsy described from her first encounters, “really just a crossroads with Gallagher’s General Store on the corner and a gas station on the other, Willard Sharpless’ blacksmith shop on the third and a marsh on the fourth.” Route 1, now a four-lane highway with a traffic light at the crossroad, she said, was easy to cross on foot any time. From the introduction she wrote for the book Andrew Wyeth: Close Friends (2001), it mirrored the sleepy quality of The Stray’s fictive “Ford.”

Betsy led a Brownie scout group; she became an authority on Pennsylvania antiques; she knitted dozens of sweaters, often for her husband. She hunted for yarns the exact blue of her husband’s eyes, says Landa, who continues to oversee the Wyeth archives. Betsy also almost always had a menthol cigarette in her hand.

Throughout, Betsy Wyeth continued to promote and educate the public about her husband’s art. She wrote the text to accompany Christina’s World: Paintings and Pre-studies of Andrew Wyeth (1982), coproduced Snow Hill, the 1995 documentary about three generations of the Wyeth family, and worked with an IBM executive in 1987 to facilitate one of the first digital art archives.

In 747, Betsy Wyeth’s back is to the mill, near where she built a studio for her husband. In 1985 this is where he would set 15 years’ worth of clandestine paintings of neighbor Helga Testorf.

The first Helga painting dates to 1971 when Betsy, potentially unaware, was selecting and editing a crate of 1,200 letters penned by her late father-in-law in preparation for publishing The Wyeths: The Letters of N.C. Wyeth 1901-1945.

The same year, a nearby museum opened; Betsy “was the energy behind” it. She assured the museum’s founder, George “Frolic” Weymouth (an artist married to Wyeth’s niece): “You build the buildings and we’ll put pictures in it.”

It’s now known as the Brandywine Museum of Art.

“Home Places” is on view at the Brandywine through July 30. brandywine.org/museum