‘Becoming Dr. Seuss’ by Brian Jay Jones: How Ted Geisel discovered his American imagination

He thought kids' lit spoke down to children and did not challenge them. So he created an entirely new kind of book for young people -- fanciful, full of crazy characters and wild and delightful language ... but also it addressed topics such as insecurity, racism, and environmental crisis.

Becoming Dr. Seuss

Theodor Geisel and the Making of an American Imagination

By Brian Jay Jones

Dutton. 496 pp. $32

Reviewed by David Silverberg

Imagine a world without the Lorax, the Grinch, green eggs and ham, or the word nerd. To be deprived of the imagination of children’s book trailblazer Dr. Seuss, born Theodor Seuss Geisel, would leave readers without the timeless tales and iconic characters that remain embedded in our collective psyche more than 80 years after the first Dr. Seuss book was published.

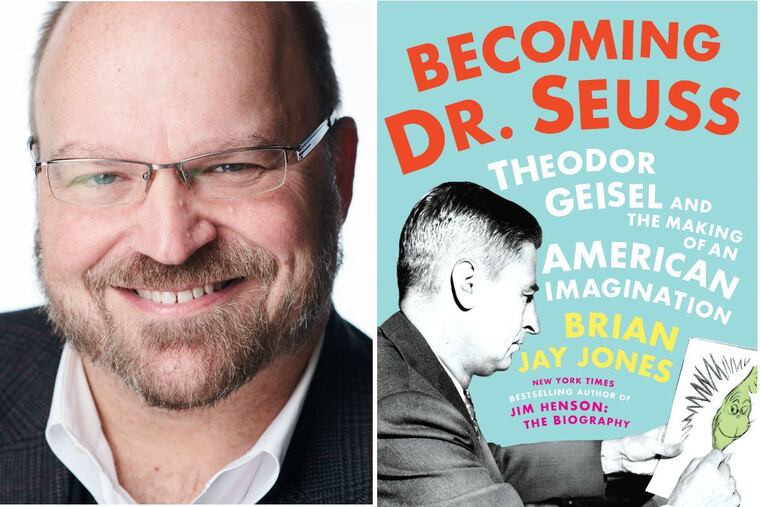

But who’s the man behind the couplets? Brian Jay Jones comprehensively answers that question in a nearly 500-page biography. Credit either Geisel’s amusing personality or Jones’ breezy writing, but Becoming Dr. Seuss never feels like a slog; rather, pages fly by, acquainting readers with Geisel’s work ethic, frequent pranks, and belief that children’s books should never be condescending or simplistic.

Born in Springfield, Mass., to German parents, Geisel read voraciously in his youth. He later claimed he read Jonathan Swift and Charles Dickens at 6 years old. His childhood was marred by anti-German sentiment during World War I: He would sometimes flee from high school with coals bouncing off his head. His fury at this kind of hate formed the backbone of The Sneetches.

At Dartmouth College, Geisel did cartoons for the college satire magazine, Jacko, and his art was used in everything from house ads to column filler. He knew he had talent, Jones writes, but he also needed to make a living a after college. Geisel brought his artistic skills to advertising, most notably for Standard Oil and the bug spray Flit. Certain ad illustrations featured creatures resembling characters any Dr. Seuss fan would recognize.

Moving to San Diego, Geisel pivoted to children’s books partly for financial reasons, but also because of a long-held frustration: "Dick and Jane" books talked down to kids and never challenged them, Geisel complained more than once. It was time to entertain and educate young readers, he thought, while wrapping the stories in playful language and invented words. (Geisel coined the term nerd in 1950 in his book If I Ran the Zoo.)

The more compelling portions of the book focus on Geisel’s tense relationship with his publisher Random House, whose editors appointed the author the president of their new Beginner Books imprint. Geisel not only had an issue with the “word list” — the 200 or so unique words authors were limited to using — but also with publication choices. His arguments with Random House brass over which books to launch were particularly telling, showing how passionate Geisel had become about advancing children’s literature.

What will undoubtedly satisfy Seussian scholars and casual readers alike is a portrait of his work schedule, which Jones chronicles as being so rigid his first wife Helen often had to pull the author out of his basement and into dinner parties where he would reluctantly socialize over cocktails. Don’t think children’s books are any easier to write than adult prose, Jones stresses. Geisel could spend days perfecting a single rhyme, lest it shine duller than the other gems surrounding it.

Pranks and jokes invigorated Geisel: He once slathered paint onto a canvas and convinced an art-loving friend it was the work of a “great Mexican modernist.” The man paid $500 for the slapdash work, but Helen persuaded Geisel to return the money.

When Jones turns to the amusing origin stories behind The Cat in the Hat and How the Grinch Stole Christmas, the book picks up in pace and intrigue. Jones writes that Geisel came up with The Lorax as a response to watching condo development envelop San Diego’s pristine coastlines. "It’s one of the few things I set out to do that was straight propaganda," Geisel says of his environmentally friendly anti-greed book.

Profiling cultural empires and their instigators is familiar territory for Jones, who also wrote Jim Henson: The Biography and George Lucas: A Life. It’s clear that Jones is experienced in extracting details from the most innocuous letter or interview, fleshing out the lives of cultural groundbreakers we’ve long admired. As all successful biographers should do, Jones doesn’t cheerlead his own writing style by adding unnecessary flourishes or similes; he lets the subject’s actions and quotes energize the book.

Thankfully, Ted Geisel is a hilarious and insightful character whose love of literature is almost as infectious as his timeless rhymes.

David Silverberg is a freelance journalist and book critic in Toronto who writes for BBC News, Vice, Ars Technica, and Now Magazine. He wrote this review for the Washington Post.