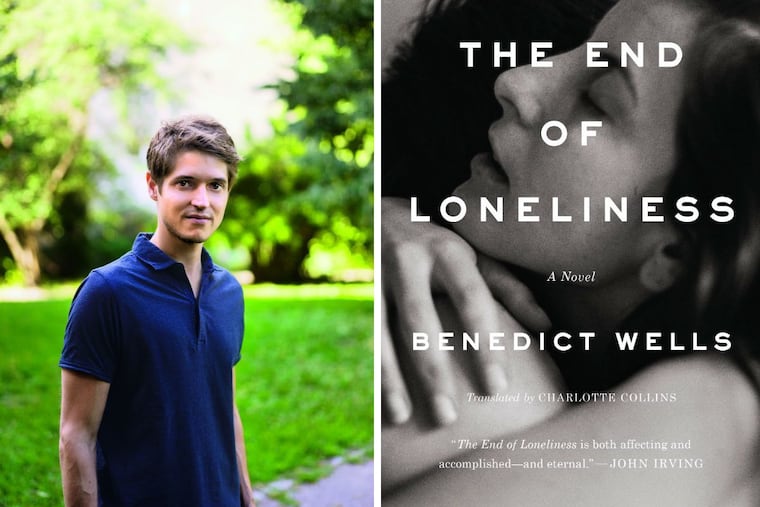

‘The End of Loneliness’ by Benedict Wells: Beginning of a fruitful solitude

Compact, smooth, understated yet passionate, this cherishable book is both a family story and a tale of a person in search of the self he is afraid to own. Despite the loss and sorrow that's coming, you have to call this a happy-ending book, in the most complex, adult, worldly sense.

This beautiful book — compact yet flowing, lovingly translated by Charlotte Collins, understated yet passionate — brings German author Benedict Wells, only 35, front and center among world writers. It’s both a family story and the tale of a man in search of the self he is afraid to own. When you reach the last words and set the book reluctantly down (you don’t want to leave the world it has woven), you have suffered and lost again and again, and you are smiling. In the most adult, complex, worldly sense, you’re experiencing that rarest of feats, a happy ending.

The End of Loneliness joins the world literature of solitude, including titles such as Gabriel García Márquez’s Hundred Years of Solitude, William Faulkner’s Light in August, Carson McCullers’ The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter, and Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. From birth to death, each of us is alone, and our essential solitude never wholly disappears. Though solitude can often be sweet, and we sure need it sometimes, it can also be painful, isolating, paralyzing. Contending with that double-sidedness is the work of a lifetime.

How, though, to contend? Wells’ tale seems to suggest that, because solitude never changes, it is we who have to change, in our attitude to our singleness, in our readiness to embrace what we really are. That can be hard and frightening. The triumph of this book is that its characters overcome monumental sadness to do this good, hard work. The story affirms the value of such spadework, even as it acknowledges how grinding and unavailing it sometimes is.

Jules Moreau and his siblings Marty and Liz grow up in a French German family. Perfect the family isn’t, and we get glimpses of the parents’ failings and frustrations, particularly a weakness in the father’s character, a fear of prudent risk-taking or change. It’s this weakness Jules must face up to, for he himself, as a loving son, has taken it on. But the family is fun and warm enough to draw us in.

When, as we know it must, misfortune blows them apart (and if the book has a failing, it’s the numerous portentous set-up sentences), the next years are hard. The author himself spent 13 years at state-run homes and schools, and the passages in which the three Moreau sibs live in such institutions are especially vivid. Liz is socially adept, magnetic, and bold; Marty is a mildly crazy, nihilist geek destined for success; Jules struggles.

None is really the person whose role he or she is acting; each must set off in search of the authentic. “There’ve been so many paths in my life,” Jules says, “so many possibilities of being someone else. ... What would be the immutable part of you? The bit that would stay the same in every life, no matter what course it took.” He’s talking to Alva, one of the book’s unforgettable creations. She, too, has sustained a permanent wound, the loss of a sister, and it pitches her into some hurtful choices. But she is also the great friend of Jules’ life, the very person his father has told him to find. In a story within the story that really constitutes a separate novella, we track these two over more than 30 years, from the 1980s to about the present.

Wells does not turn away from suffering, loss, or death. What’s not all right is not all right and can never be. Bad news unleashes in Jules “a force so archaic that I was instantly struck dumb; it robbed me of all feeling, and for a moment I didn’t know what to say or do.” Although certainly an emotional novel, The End of Loneliness is not sentimental.

A nice trick, as, again rare to find, the family members do work their way into a different life, the one they were living, or could have lived, had they only known.

Which is why I marvel at The End of Loneliness. Underneath its steady flow, there is a bedrock of kindness, of belief in the power of those we love to bear us up. They can’t and won’t solve our problems, but they can help, and they do. Jules needs his brother and sister, needs them to work back round to him; and he needs to work back to them, back through addiction, conflict, motorcycle crashes, lines going dead, simple refusal to see. He must free himself from longing for the feelings of childhood, leave behind the father’s legacy, accept that he is worthy and capable. I might add that he’s a dad, and that will help.

It “was only very late,” he says, “that I understood that I myself am the sole architect of my existence.” This coexists with the somewhat (and happily) contradictory “The only way we can overcome the loneliness is together.” Jules will always be lonely, but we feel he will seldom henceforth be altogether alone.