Independent bookstore owners, including one in Haddonfield, look back at a year spent trying to stay afloat

Some independent bookstores prospered during Year One of the coronavirus pandemic. Others decided to call it a day. And for others yet, it's too soon to predict which way the plot might twist.

Some independent bookstores prospered during year one of the coronavirus pandemic — their stories silver linings that pop against so much darkness. Others decided to call it a day. And for some, it’s too soon to predict which way the plot might twist.

The owners of six indies were asked about how they weathered the year. What follows is an oral history of these shops’ highs and lows as the pandemic knocked life and business upside down.

March

Emily Powell, owner of Powell’s Books in Portland, Ore.: One of the first things to happen in Portland was that the public libraries closed down, so more people came into our stores than we normally would have seen. On March 15, we reached a tipping point. The store opens at 9 a.m., and by 10 we said, “We need to close. Everybody needs to leave.”

Michael Fusco-Straub, who runs Books Are Magic in Brooklyn with his wife, novelist Emma Straub: The week before the shutdown was a really weird week for us, because we had these two giant off-site events. One had around 800 people, and the other had 500, and it was nerve-racking. Within a couple days, we had turned on a dime and basically became a fulfillment center for online orders.

Malik Muhammad, who runs Malik Books in the Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza in Los Angeles with his wife, April: For us, it was devastating, because we got a memo that said, “The mall is gonna be shut down, and you have 24 hours to gather everything you need.” And that was going to be the only time you were able to have access to your business. All our inventory was locked up in the mall. It was horrifying. We in the underserved community, we don’t have months of resources sitting around, like savings and things like that.

April and May

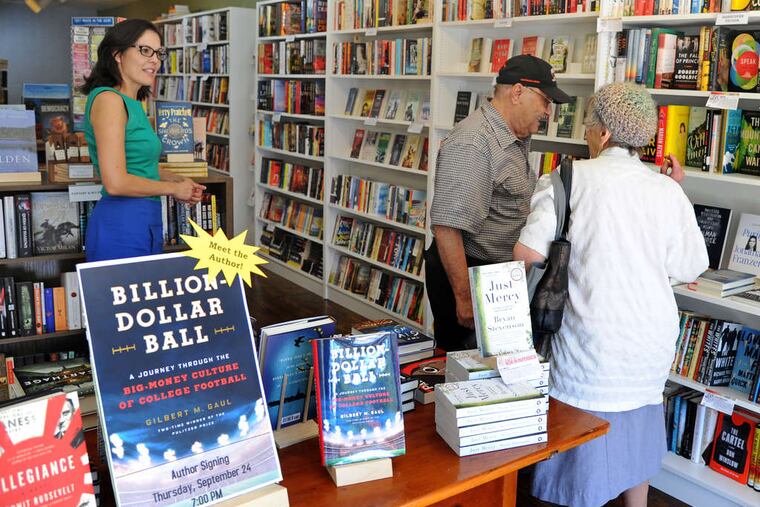

Julie Beddingfield, the owner of Inkwood Books in Haddonfield, N.J.: In November 2019, we had signed a lease to move into a new, bigger location so that we could expand everything we were doing. Once the pandemic started, I had to decide: Am I moving or not moving? And I’m looking at my husband like, I don’t know what to do. If we move, what if we don’t get to reopen? What if we shut down? And he said, “If you think you want to be there in a year, then just do it.”

Janet Berns, who owns the Book Nook in Monroe, Mich.: I work the store mostly by myself. We’re really small. You look at some local chain that has four or five big stores, and you say that’s an independent bookstore — no, no, no. I’m an independent bookstore. It’s just me. There’s an alley that runs behind the building, so I said, OK, this is going to be our curbside. You’re going to run through the alley, give me a call and we’ll come running out. I got my steps in on my Fitbit, running back and forth.

Muhammad: I learned a long time ago that the things you can’t control and can’t do anything about — you can let them bother you and worry, or you can figure out what to do. So we tried to find ways to market our website and grow our business online. I got in touch with some of my suppliers and had them divert books that were going to the store to come to our home instead. So we had some inventory and we, as a family, would package up the books and either ship them or, if it was local in Los Angeles, deliver them. We would jump in the car with our two children — we called them field trips.

» READ MORE: Betting on books, lawyer opens Haddonfield shop

Ramunda Young, who own MahoganyBooks in Washington with her husband, Derrick: We immediately created MahoganyBooks Front Row: programming that allowed people to attend dynamic conversations from the comfort of their own homes. And we started selling book bundles and mystery boxes and things like that online.

Fusco-Straub: The store basically got turned upside down. We had boxes of books all over the floor — at the height of it, we were getting 300 to 400 orders a day. But it was a lot more labor to get a book into somebody’s hands. There was a core group of three or four of us who would go in there every day, process online orders, and ship. I would pick everybody up in my car in the morning and then buy everybody lunch. That was my thing, seven days a week, for nearly all the 16 weeks we were closed.

Beddingfield: My husband and I would fan out in our two cars and drive all over tarnation delivering books. He made a really good point. He’s like, “I just drove 10 miles to deliver a $15 book. I’m pretty sure you’re losing money on this gig.” But the libraries were closed, and people needed their books. It felt like doing a community service. And it was lovely: People would leave notes taped to their door. Someone baked me cookies, and sometimes it was just people frantically waving through the window. Because I was one of the few people who was out. I had people tell me later, “I felt like I was living the pandemic through you because you were out in the community and we were all holed up at home.”

June through August

Ramunda Young: Throughout the climax of emotional events that were happening across the nation, there was this almost immediate outpouring of customers — white customers, to be frank — looking for books that pull back the veil on racism. There was a gentleman on social media who came out and said, “If you’re gonna go and look for Black books, don’t go just anywhere. Go to a Black bookstore.” And people did. If you had a website that was functioning and easy to use, people were coming from all across the nation.

Powell: The country had George Floyd, and the social justice movement that arose in the wake of that, and then we had huge wildfires in Oregon in August. Our operations were down for the better part of a week because people couldn’t leave their homes. It was very intense smoke. I mean, it was really awful. I continue to feel at this point in this whole ordeal that every six to 10 weeks, something else happens. I’d give my left arm for any kind of consistency or predictability to our work.

Ramunda Young: The biggest thing that was out of our control was the book industry. There was a paper shortage, and some of the printers were acting up. So we had all these customers saying, “I want these books.” And now we couldn’t fulfill the orders. And it wasn’t a MahoganyBooks thing; it was an industry thing. So the tenor kind of switched from, “I want to learn and educate myself about white privilege” to, “I’ve been looking for my book forever. Where is it? Give me my refund.”

Beddingfield: We were allowed to open with limited capacity. I was really worried about having to be the mask police. I can be assertive when I need to be, but the bigger thing for me was that as a manager of other people, I had to really step up. I had to be the one to set the example. So I told the staff, we will enforce the mask, and if you’re not comfortable — if you see someone not wearing a mask — I will say something to them. And I said, “You have my blessing to say whatever you need to say to people to feel safe.”

“I hired a bouncer — I call her the bookstore bouncer. She worked on Fridays and Saturdays, sitting at the door and counting people.”

Berns: The older I get, the less patience I have for nonsense. And if you’ve ever worked in retail, there’s a lot of nonsense. I love my books. I love selling books. I don’t want to talk politics. And the whole thing got political. I’m a breast-cancer survivor, and I didn’t want to deal with people who didn’t want to wear a mask. So we didn’t even try to open — we were strictly doing curbside.

Muhammad: We could do curbside delivery, but the mall was closed. And part of being in a mall is foot traffic. So we were devastated financially, of course. We were upside down. They were also trying to sell the mall — during a pandemic! It created a perfect storm because the community felt that the mall was closed, period. If you walked up to 10 people, nine of them would say, “I thought the mall was closed.” It was a ghost town. We spent all these years developing a clientele that came to our location, only for this to happen. So we started a GoFundMe to help assist us during these turbulent times. And so many people supported us that we’re just overwhelmingly grateful.

September through December

Beddingfield: We allow 10 people in the store at a time, and that includes us. We’re just constantly counting people. The holiday season was insanity. I have never worked as hard in my entire life, and I was an attorney for 12 years. We had lines down the street, and at one point the people at the coffee shop next door were like, “Is there a rock star in there?” So I hired a bouncer — I call her the bookstore bouncer. She worked on Fridays and Saturdays, sitting at the door and counting people.

Muhammad: I was already in debt, I couldn’t pay my debt, and I had to go in debt even further to put the store in a position where we could continue in the midst of this pandemic. It was a leap of faith. We’ve been biting our nails.

Berns: On Nov. 1, we announced that we won’t reopen. I have a lot of mixed feelings about this. I worked for the original owner out of high school, and then I took over in 1969. In November we celebrated our 51st anniversary.

Looking back, and forward

Fusco-Straub: It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do. It was backbreaking. I was gone from the house for 10 hours a day, and most days I was lucky if I walked in the door to say good night to [my kids]. The good thing is that we learned so much that the store right now, as a whole, runs better than it ever would have if we hadn’t gone through it. When things get back to normal, I think it’s going to be operating on a level I never even thought could exist.

Ramunda Young: It was hectic. It was tiresome. It was draining. It was exhausting. But, man, it was glorious. There’s a lot of pride and fulfillment. Going through a pandemic allowed us to reach our goal — to get Black books into people’s hands, no matter where they live — to a level we had not anticipated, and it was a gift.

Beddingfield: I had many moments of just losing it, and I could do that because I was there by myself. I could swear, I could curl up in the fetal position and cry. I was with my books, and they don’t judge. Still, at the end of the day, you run these reports and look at how many books you sold. And as a business owner, you’re like, “Oh, great sales.” But as a human, you go, “That’s how many books we put out there in the world.”

Muhammad: They still haven’t sold the mall. Two deals fell through. The damage is done — nobody is in this mall. It’s been sleepless nights, it’s been anxiety, it’s been horrifying as a father with teenagers. You’re thinking about your ability to provide, you know? I mean, if they sell this mall, they’re going to close it and we’re out. And I’m thinking, we’re in a pandemic, what are we going to do?

Berns: The store is sitting here full of thousands of books, and the door is locked. Once we move the rest of this inventory out, I’ll be strictly online. I just made the conscious choice that, you know what? We had a good run. It’s not worth it. I’m not going to let this disease take me out. It’s a killer, literally and figuratively.

Derrick Young: I miss talking with my customers, engaging with them. I miss having book clubs in the store. I miss having authors come into the store. We became booksellers to sell books. I didn’t become a bookseller to be a fulfillment center or ship books. I just want to talk to people about books.