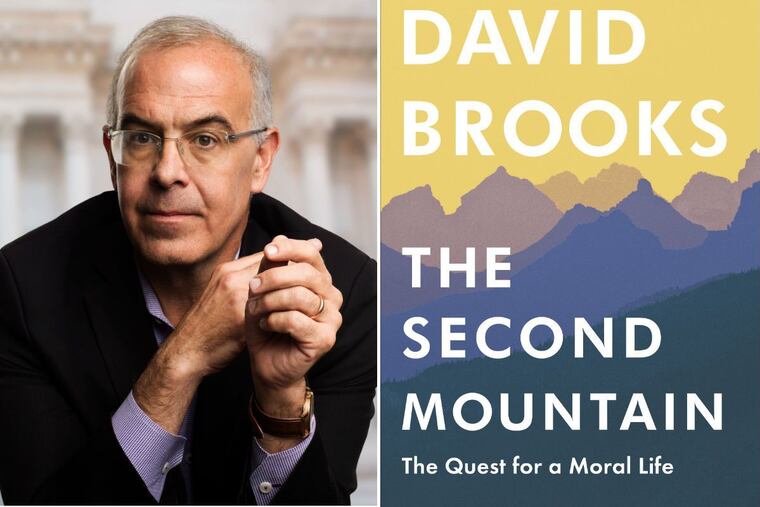

David Brooks’ 'Second Mountain’: A redemption story for self and society

The author, one of the most influential columnists in America, has traced his emotional and moral journey from his ambitious 30s to sadder days, and now to an emotional and moral upswing. He sees hope for this country in learning to cultivate our currently ailing human connections.

Marc Freedman

The Second Mountain

The Quest for a Moral Life

By David Brooks

Random House. 346 pp. $28

Reviewed by Marc Freedman

In his new book, David Brooks charts his path from the valley of despair to the heights of understanding. In the words of "Amazing Grace," "I once was lost, but now am found / Was blind, but now I see."

The Second Mountain continues the intellectual and personal exploration of his previous best sellers. He wrote Bobos in Paradise as an ascendant 30-something, chronicling the self-centeredness of bourgeois bohemians at the intersection of " ’60s values and ’90s money." In The Road to Character 15 years later, he was a quietly despairing 50-something, struggling to locate meaning and desperate “to save my own soul.”

The Second Mountain finds an older and wiser Brooks on the road to something beyond individual character improvement. Climbing the first mountain, he was in search of résumé virtues: "the skills you bring to the marketplace." On the second mountain, it’s time to secure eulogy virtues: "the ones that are talked about at your funeral." But now there’s a bigger story to tell and a bigger problem looming.

The personal transformation leading to the second mountain, Brooks observes, connects in essential and timely ways with our predicament as a nation. “The foundational layer of American society — the network of relationships and commitments and trust that the state and the market and everything else relies upon — is failing,” he writes. “And the results are as bloody as any war.”

The consequences of our rampant individualism — tribalism and social isolation reflected in an epidemic of suicide, addiction, and despair — have reached crisis proportions, he writes. But personal renewal, second-mountain-style, can do more than save our souls. It can rescue us from societal collapse.

Here Brooks joins another longstanding American tradition, extending back to Alexis de Toqueville, critiquing the excesses of “hyper-individualism” while urging salvation through purpose beyond the self.

Brooks isn’t waiting for a charismatic politician to deliver us. He pins his hopes instead on a growing band of innovators he believes hold the potential to create a new culture, revamp our civic institutions, and seed the ground for broader reforms. For Brooks, social transformation follows personal transformation.

He finds these paragons of “deep relationality” — what Father Gregory Boyle calls “radical kinship” — in every community. These activists, often with their own second-mountain stories, are making it easier for others to live lives of deeper connection. Brooks recounts how spending time with these trailblazers has made him a more committed, more caring person.

He tells the story of David Simpson and Kathy Fletcher and their Washington nonprofit, AOK (All Our Kids). Simpson and Fletcher have taken in dozens of teenagers facing adverse circumstances and formed a community. Brooks eats dinner with them on Thursday nights, observing how the communal table — the listening, supportive words, and sense of belonging — changes lives.

In Baltimore, social entrepreneur Sarah Hemminger has created Thread, an initiative that, Brooks explains, "weaves a web of volunteers around Baltimore’s most academically underperforming teenagers." The program connects community members, often across generations, to promote understanding and strengthen the social fabric. Thread’s participants support one another, making it impossible to distinguish between giving and receiving.

Inspired by such paragons of purpose, Brooks has moved from observer to activist. Last year, he launched a new initiative at the Aspen Institute to tell the story of “weavers” like Simpson, Fletcher, and Hemminger and strengthen the grass-roots movement they represent.

The Second Mountain is an ambitious volume, part sermon, part self-help guide, and part sociological treatise, replete with quotes and stories from Tolstoy, Moses, Orwell, and others. The book ends with a list of more than 60 numbered prescriptions. At times, it can feel overwhelming, even overstuffed.

Yet the book is deeply moving, frequently eloquent, and extraordinarily incisive. It is hopeful in the best sense. It’s not just what Brooks says but what he embodies. It’s very much a book about the second half of life from an astute social observer, himself closing in on 60 and part of the population explosion moving beyond midlife.

Researchers show that there is a U-bend of happiness in life — on average, we’re upbeat early on, then hit the skids in midlife before growing far happier later. Equally important, research from Stanford psychologist Laura Carstensen explains that as we realize there are fewer years ahead than behind, we are driven toward precisely the deep connections that Brooks places front and center. What’s more, relationship skills, including emotional regulation and empathy, blossom in later life.

As it turns out, Brooks and his second-half compatriots could be the very force to take us to the second mountain — and into the promised land.

Marc Freedman, chief executive of Encore.org, a national nonprofit mobilizing older Americans to create a better future, is the author of “How to Live Forever: The Enduring Power of Connecting the Generations.” He wrote this review for the Washington Post.