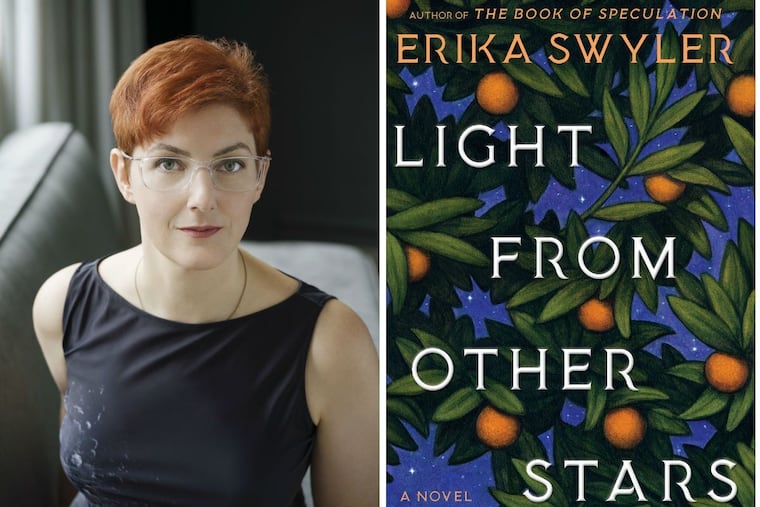

Erica Swyler’s ‘Light from Other Stars’: Sci-fi for the rest of us

The story -- of a resourceful young woman and her scientist father -- has familiar beginnings but takes very original twists and turns. And this is one science-fiction author who knows as much about the human heart as she does about entropy and space travel.

Light from Other Stars

By Erika Swyler

Bloomsbury. 304 pp. $27

Reviewed by Marion Winik

Newsday

One of the first books I ever fell in love with was A Wrinkle In Time by Madeleine L’Engle. The book was published in 1962; its staying power is illustrated by last year’s Hollywood film version starring Oprah, Mindy Kaling, and Reese Witherspoon. A pioneering work of young-adult science fiction, it tells the story of an bright little misfit girl whose parents are scientists. Her father disappears after falling victim to his own experiment, studying a tesseract that melts time and space; she is determined to save him.

Erica Swyler’s Light from Other Stars is also about a brilliant misfit girl with scientist parents whose father falls victim to his own experiment, the attempt to create a machine that alters time. It adds many other elements to the mix, but this moving premise is part of what will make Swyler’s second novel (it follows her well-received 2016 debut, The Book of Speculation) appeal to those who don’t usually read science fiction. There’s also plenty of science for faithful fans of the genre.

Light from Other Stars tells two stories in parallel. One is set some time in the future, aboard a spaceship called Chawla, where four astronauts — two women and two men — are on a deep-space journey to colonize a new planet. The urgency of their mission is created by "droughts, wildfires and Manila sinking," Swyler writes. "Climate change had at last caught and surpassed the rate of technological advances."

One of them is Nedda Papas, originally of Easter, a fictional Florida town of orange groves and NASA employees. The second narrative thread is set in her childhood, when her father, Theo Papas, laid off by the space agency and emotionally gutted by the death of a son, became obsessed with building a machine that slowed down entropy. Eleven-year-old Nedda was in the dark about her baby brother and about the fact that her beautiful mother, Betheen, was a scientist before she became a baker, but her ferocious precocity enabled her to grasp her father’s work and help her mother try to save him.

It also made her an obsessive fan of the space program, and when the Space Shuttle Challenger — carrying Nedda’s idol, astronaut Judy Resnik — blew up on Jan. 29, 1986, she was watching on TV in her sixth grade classroom. The shudder that shook her school at the moment of the launch also reached her father’s lab, and his machine, and a tragedy was set in motion.

Meanwhile, aboard the Chawla in some unspecified time in the future, Nedda and her colleagues are living the spaceship life, which Swyler has imagined in detail. As their bodies are monitored by medics on Earth, a futuristic “printer” spits out antidepressants, benzodiazepines, and other drugs they prescribe. Though put to sleep for weeks at a time to prolong their endurance of shipboard conditions, the space travellers all are going blind due to the lack of gravity. When something goes seriously wrong, Nedda has to try to fix it while she can still see. Her experience back in Easter will be crucial.

As a non-sci-fi reader, I found pleasure in Swyler’s writing as well as her story. At one point, she describes the quality of longing that all humans share: "Yearning for a lover, yearning for a houseboat ... for a baby, to finally be a mother; for fame; for sleep without nightmares; for one day without aching joints; for a job; for Missy to come back; for someone to actually listen, just once ... for the sweet orange soda they stopped making; ... for a father."

Only a writer like Swyler, one who understands the human heart as well as she understands entropy and space travel, can write a book like Light from Other Stars — science fiction for the rest of us.

Marion Winik reviews books for Newsday.