Exploring the legal world of Hamilton — and ‘Hamilton’ — in collection edited by a Drexel law professor | Book review

The book’s 33 essays take Hamilton (the man and the musical) to a new level, at once imaginative and informative.

Hamilton and the Law

Edited by Lisa A. Tucker

Cornell. 315 pp. $39.95

Reviewed by Ronald K.L. Collins

The past defines us, but only in the way we interpret it. For several generations Thomas Jefferson was the quintessential founding figure. Then came the story of Sally Hemings, his enslaved mistress, and his patina of glory faded. While Alexander Hamilton (the captain of commerce) has long been a towering figure in constitutional law, his cultural stock struggled to rival Jefferson’s. Then Ron Chernow’s widely read 2004 biography burst onto the historical stage, and the first treasury secretary’s popularity ticked up considerably. But the real bull market came with Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton: An American Musical, a Broadway blockbuster that artfully and profoundly reinvented Chernow’s biography.

We live by narratives. By that measure Hamilton the musical retold history in ways that invited us to rethink how we understood our heritage. That past was given new meaning as Daveed Diggs (as Jefferson) pranced around while engaged in sharp repartee with Miranda (as Hamilton); as Christopher Jackson (as George Washington) fretted over the future of the republic while Jonathan Groff (as King George III) confidently proclaimed, “You’ll be back.” In this inventive blend, history came alive as never before.

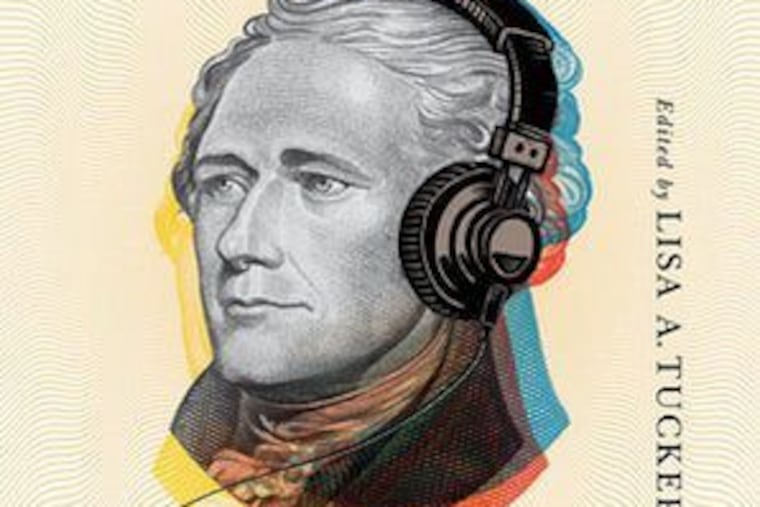

Against that backdrop comes Hamilton and the Law: Reading Today’s Most Contentious Legal Issues Through the Hit Musical, an engaging and impressive book edited by Drexel University law professor Lisa A. Tucker. Her creativity in conceiving this work finds like-minded artistic expression on the book’s cover: a pop-art, color-tinted sketch of Hamilton in headphones. Aided by a chorus of commentators — lawyers, law professors, former solicitors general, a Marine Corps University professor, and a novelist — the book’s 33 essays take Hamilton (the man and the musical) to a new level, at once imaginative and informative.

On the one hand, the test-the-limits narrative of Hamilton seems ill-suited for the law: too creative, too fluid, too debatable. After all, black-letter law is quartered in conventions that resist the retelling of an orphan’s multilayered story touching on themes of race, class, and immigration. On the other hand, there is Hamilton the lawyer, banker, statesman, and treaty-maker. Then there is Hamilton the Constitution drafter and Federalist Papers coauthor. Combined, they make for a perfect historical musical adaptation, the kind that begs for both a legal and a cultural interpretation.

In the musical and the book there is at least one constant: lucid, captivating cultural commentary. In the dramatic mix, consciences are pricked and ideas bloom as actors proudly proclaim: "Immigrants, we get the job done." Still, the cultural and constitutional jobs remain undone, which is a testament to Hamilton's elusiveness and Miranda's genius. His musical inspires us to return to Hamilton's world and consider it anew, first through his inventive lens and then ours.

While there is more than a dollop of Hamiltonian glorification in some of the book’s essays, taken as a whole they impressively link the musical to the legal side of Hamilton’s story, with contemporary relevance. Two noteworthy examples are the thought-provoking essays by Richard Primus, on the “operative” meaning of the “original meaning” of the Constitution, and Neal Katyal, on how Hamilton the musical captures “the essence of America and immigration” better than the Roberts court’s decisions do. Topics such as federalism and separation of powers are also portrayed with novel clarity in Miranda’s musical and with nuanced appreciation in Tucker’s anthology.

Of course, the book discusses dueling and Vice President Aaron Burr’s killing of Hamilton. Several essays discuss how that infamous face-off prompted anti-dueling laws while augmenting defamation law as a civil substitute. Additionally, the legendary gunfight led to new restrictions on gun ownership. Though largely detached from the musical, Ian Millhiser’s discerning essay uses the 1804 event to tease out the philosophical import of the constitutional duel between the two men over the meaning of the 1787 document.

The hip-hop musical and this anthology of legal essays also reveal the connections between two seminal dates: 1776 (the American Revolution) and 1619 (slavery comes to Jamestown). The scope of those themes is explored in the four essays organized under the heading “We’ll Never Be Truly Free: Hamilton and Race.” Christina Mulligan, for example, uses the play to examine an “alternative reality,” one “in which Alexander Hamilton, George Washington, and their associates actually were people of color.” The hoped-for result is a moment of reflection to reconsider how “Americans understand and relate to the Founding era.” That is, who are the “we” in the Constitution’s “We the People”? And why was there a need for a “more perfect Union”?

Ours is an age of shifting tectonic plates, realigning the history in which we are grounded. Tucker turning to Miranda’s musical rather than Chernow’s biography is a novel move. And yet Hamilton’s life in “musical-theater land,” as Miranda cast it, and Hamilton’s reincarnation in legal-literature land, as Tucker framed it, remind us that where we stand determines what we see. Perspectives change. As they do, so does our understanding of history. After all, what if, as reported by the Schuyler Mansion State Historic Site, Hamilton himself bought and sold enslaved people?

Collins is a retired law professor and co-director of the History Book Festival in Lewes, Del. This review was written for the Washington Post.