‘Hamnet’: Shakespeare’s greatest tragedy was personal | Book review

Irish writer Maggie O'Farrell's novel tells the story of the Bard's lost son with the urgency of a whispered prayer — or curse.

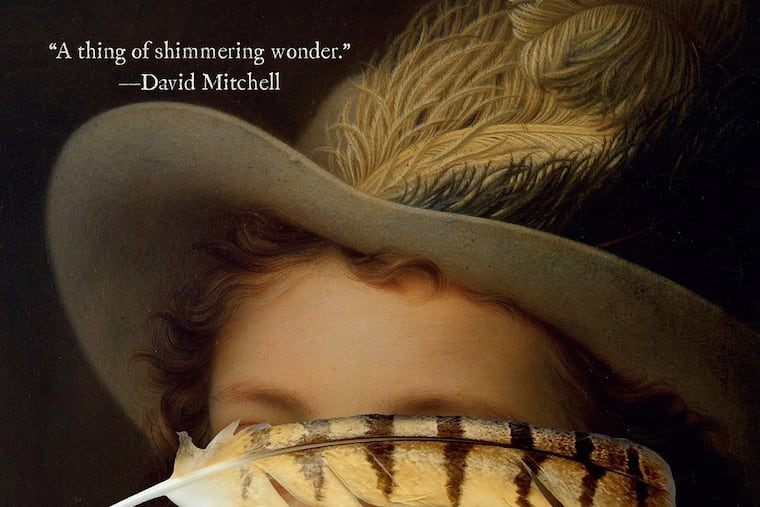

Hamnet

By Maggie O'Farrell

Knopf. 305 pp. $26.95

Reviewed by Ron Charles

On Aug. 11, 1596, William Shakespeare's only son, Hamnet, was buried. He was 11 years old.

Almost nothing more is known about the boy's brief life. Four centuries later, his death is a crater on the dark side of the moon. How it impacted his twin sister and his parents is impossible to gauge. No letters or diaries — if there were any — survive. The world's greatest poet did not immortalize his lost child in verse.

Instead, we have only a few tantalizing references in Shakespeare’s plays: the laments of grieving fathers, the recurrence of twins and, of course, a tragedy called Hamlet. But aside from the name — a variant of Hamnet — attempts to draw comparisons between that masterpiece and the author’s son are odorous. We’re stuck, as we usually are, projecting our own sympathetic sorrow on the calamities of others.

To this unfathomable well of grief now comes the brilliant Irish writer Maggie O’Farrell with a novel titled Hamnet that’s told with the urgency of a whispered prayer — or curse.

Unintimidated by the presence of the Bard’s canon or the paucity of the historical record, O’Farrell creates Shakespeare before the radiance of veneration obscured everyone around him. In this book, William is simply a clever young man — not even the central character — and O’Farrell makes no effort to lard her pages with intimations of his genius or cute allusions to his plays. Instead, through the alchemy of her own vision, she has created a moving story about the way loss viciously recalibrates a marriage.

The novel opens in silence that foretells doom. "Where is everyone?" little Hamnet wonders. He wanders like a ghost through the empty house and the deserted yard, calling for his grandparents, his uncles, his aunt. "He has a tendency," O'Farrell writes, "to slip the bounds of the real, tangible world around him and enter another place." But he's no spectral presence yet. His twin sister, Judith, has suddenly fallen ill, and Hamnet needs to find their mother. She'll know what to do. She's an herbal healer, equally revered and feared in the village. "Every life has its kernel, its hub, its epicenter, from which everything flows out, to which everything returns. This moment is the absent mother's," O'Farrell writes. "It will lie at her very core, for the rest of her life."

Between the hours of this fateful day, the story jumps back years. We see William's unhappy adolescence as the son of a cruel and disreputable glover. One day, while teaching Latin to bored children in a country schoolhouse, he spots a young woman gathering plants along the edge of the woods. History knows her as Anne Hathaway, but O'Farrell uses the name her father gave her in his will: Agnes. Neighbors whisper that she's "the daughter of a dead forest witch … too wild for any man."

That's your cue, William!

Soon, he and Agnes are acting out "hot blood, hot thoughts, and hot deeds" — including the hottest sex scene ever set in an apple storeroom.

This is a richly drawn and intimate portrait of 16th-century English life set against the arrival of one devastating death. O'Farrell, always a master of timing and rhythm, uses these flashbacks of young love and early marriage to heighten the sense of dread that accumulates as Hamnet waits for his mother. None of the villagers know it yet, but bubonic plague has arrived in Warwickshire and is ravaging the Shakespeare twins, overwhelming their little bodies with bacteria. That lit fuse races through the novel toward a disaster that history has already recorded but O'Farrell renders unbearably suspenseful.

Dead center in the novel, the author momentarily arrests the story of the Shakespeare family and transports us to the Mediterranean Sea. Here, in a chapter just a dozen pages long, we get a gripping lesson in 16th-century epidemiology. Then as now, commerce and travel are the engines of disease. A glassmaker in Venice, a monkey in Alexandria, a cabin boy from the Isle of Man — they all play small but consequential roles in the intricate chain of transmission as infected fleas jump from body to body, sowing illness across Europe. It’s a fascinating and horrific demonstration of the same forces now driving a different pandemic more than 400 years later. We may have better medical technology, but our frantic missteps sound like echoes of the Renaissance.

But O'Farrell isn't merely delaying the inevitable tragedy at the heart of her story; she's creating the context to help us feel its full impact on Hamnet's parents. Agnes is a skillful woman married to a restless man whose talents are more imaginative than practical. Constrained by the demands of motherhood and the limited opportunities of the time, she must exercise her influence indirectly and stealthily. The moves she makes to keep her children healthy and her spouse happy represent the hidden sacrifices that countless women have made, without thanks or credit, to support their husbands' ambitions.

That delicate negotiation grows far more perilous when the couple endures the death of a child. No two spouses respond to such a loss in harmony, and O'Farrell is at her most sensitive here, detailing the unspeakable anguish that strips Agnes of her confidence and propels William into the imaginary world of his comedies and tragedies.

The dark months and years of mourning that fall over the Shakespeare family would seem a slough of despair after the frantic efforts to save Hamnet’s life, but in O’Farrell’s telling, grieving is a harrowing journey all its own. The novel’s final scene offers a miraculous transformation — no, not a Winter’s Tale resurrection — but the revelation that love can sometimes spark.

From the Washington Post.