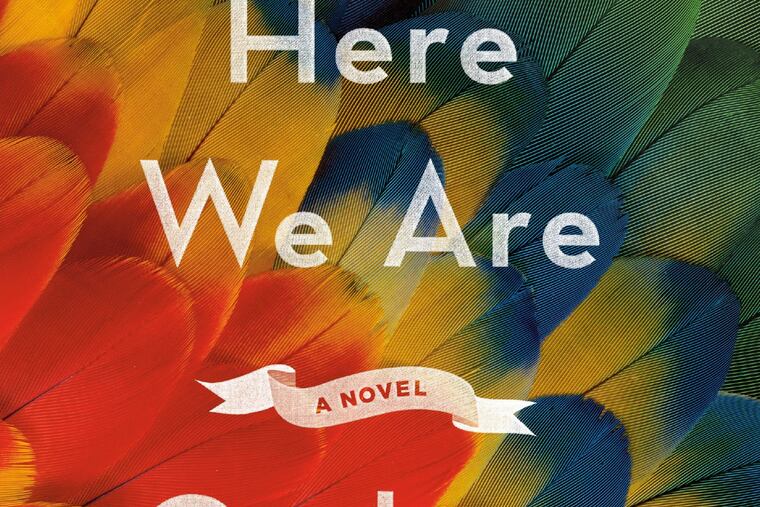

In ‘Here We Are,’ Booker Prize winner Graham Swift casts a spell | Book review

His slim new novel transports us to a seaside theater in Brighton, England, during the summer of 1959.

Here We Are

By Graham Swift

Knopf. 208 pp. $22.95

Reviewed by Ron Charles

Catching a bullet and making the Statue of Liberty disappear are awesome tricks, but the best magicians don’t need such extravagance. I learned that truth long after hanging up my cape and leaving the birthday party racket for good. Despite years of admiring David Copperfield, the only time I felt the disorienting amazement of actual magic was while talking with a street performer outside a Boston subway station. His setup couldn’t have been more modest, but when he made a card appear under my own hand, I stumbled around all day like I’d been in the presence of Merlin.

Graham Swift is no common street performer — he won the Booker Prize in 1996 — but he appreciates the transcendent artistry of small works perfectly performed. His slim new novel, Here We Are, transports us to a seaside theater in Brighton, England, during the summer of 1959. It’s about young love and the little acts of chance and villainy that realign lives.

The theater is nothing special, Swift assures us, just a variety show sporting jugglers and plate-spinners, singers, and ventriloquists. But the man who holds the reins is a dashing young emcee named Jack Robinson. The audience has the impression “that it was his show,” Swift writes. “They came to be taken under his wing and it wouldn’t have been the same without him. Your pal for the night, your host with the most. Off stage he’d say he was just the oil in the wheels — the oilier the better.” That’s not a bad description of this stylish narrator, too, who keeps the story sliding along so quickly that you’ll barely notice his sleight of hand.

It’s Jack’s idea to give his old army buddy, Ronnie, a break. Ronnie — known professionally as “Pablo” — has an impressive magic act. With his red-lined black cape, white gloves, and “bold fluid movements,” he looks like “Count Dracula’s little brother.” What he needs, though, is a sexy assistant, and as luck would have it, Evie is the only one who answers his ad. “They were a natural pair,” Swift writes. “The tricks were good, but she was the best trick of the lot.” He runs swords through Evie; he makes her levitate; he makes her disappear — and reappear. “The act had become a fluid phenomenon, yet full of thrilling tension. You never knew what might happen next. This in itself became part of the attraction.” The audience on the pier goes crazy for the two of them. The local paper says they’ve “taken Brighton by storm.”

Although they're all friends that summer — "a lopsided trio" — Ronnie and Evie's magic act might even be more popular than Jack himself. Of course, as emcee, Jack doesn't mind; the success of the show is all that matters. But poor Evie finds her affections sawed in half.

Starting with that ambiguous title, Here We Are is about the interplay of stage magic and life’s tricks. Like Anne Enright’s Actress, which was published earlier this year, Swift’s novel explores the tension between persona and character, the strain of maintaining public and private personalities. Actors, at least, have a professional excuse; the rest of us, he suggests, perform free, donning one costume and role after another. The trouble is we rarely admit it.

Five pages into Here We Are, Swift is already dropping clues about what’s ahead for these summer friends. “Ronnie and Evie,” he writes, “having had a remarkable debut, coming from nowhere to achieve summer fame and having secured for themselves, it would seem, future booking, even a whole career, never appeared on stage again. Ronnie never appeared again at all.”

If this were a tweedy English mystery, the magician’s body would wash up on shore on the last day of summer. But Swift is pursuing subtler crimes and larger mysteries. He has a penchant for long-festering secrets that warp lives. Indeed, his 2007 novel, Tomorrow, was a ridiculous fever dream of concealed information. Here, fortunately, Swift gets the tone just right, and the magician’s act provides a wry context for Ronnie’s disappearance.

But the real magic may be the way Swift moves through time. Flashbacks unveil young Ronnie’s magical childhood during World War II, when London shipped children out into the countryside for safety. And other sections leap ahead half a century to show Evie’s retirement in the early 21st century.

Then and now, so much depends on the alchemy of luck and desire. With a sigh, Swift captures the tragicomedy of human life in a single phrase: “The things that we do.” Before we know it, here we are, looking back on lives that will never give their secrets away.

From the Washington Post.