‘Joan of Arc in the English Imagination’: Girl, warrior, witch, myth, and more

The author, a Maryland professor and expert on the young French warrior, uncovers four centuries of opinions on Joan, a messy collage of misogyny, nationalism, guilt, justification, inquisition, and awe surrounding her still-amazing legacy.

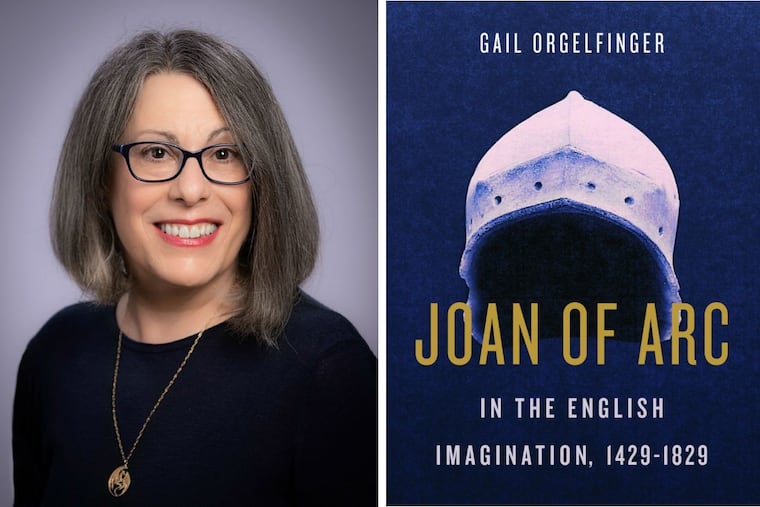

Joan of Arc in the English Imagination, 1429–1829

By Gail Orgelfinger

Pennsylvania State University Press. 248 pp. $89.95.

Reviewed by Scott Manning

The most prevalent image of Joan of Arc among Philadelphians is her gilded equestrian form near the Art Museum, which can also be seen on the side of our buses and in last summer’s Sand Sculpture Spectacular at Liberty Place. Those who recognize her likely share the reactions of English writers visiting her statue in Orléans during the 400-year period after this young warrior came onto the world’s stage: How did she accomplish so much at such a young age with so much stacked against her?

How, indeed, a teenage girl led men in battle, skillfully deployed gunpowder artillery, fought in at least 11 battles and sieges, liberated 30-plus cities, and survived three wounds — a resume that would impress today regardless of gender? And how did she endure months of interrogation from men trying to entrap her?

But what Philadelphians never have to ponder is their culpability in her execution, something the English grappled with immediately following her demise.

Gail Orgelfinger, senior lecturer emerita at the University of Maryland-Baltimore County and founding member of the International Joan of Arc Society, takes a detailed look at how the English viewed Joan in the four centuries after her death. The result is a work of panoramic scope that touches an array of perspectives, from that of an unidentified soldier present at her burning all the way up to Shakespeare. Predecessors attempted to paint an evolving English opinion, one that started out harsh but progressed over time. This book presents the messy collage of misogyny, nationalism, guilt, justification, inquisition, and awe surrounding Joan of Arc’s legacy across all periods.

Orgelfinger starts the book with the subject’s voice, dedicating the first chapter to how Joan viewed the English. After all, with a book dedicated to how the English viewed her across four centuries, it’s worth discussing how Joan viewed them during her brief 19 years. Following her childhood up to the Siege of Orléans and then skipping to Joan’s capture and trial, Orgelfinger concludes that “defiant words were part of Joan’s stock in trade, but profane or personally insulting ones were not,” even when faced with the most vulgar of insults. That is useful to a much broader audience, including military historians who seek to understand how a medieval commander viewed an opponent.

Turning to the English, Orgelfinger focuses on each writer’s predecessors, influences, and the times in which he or she wrote. Themes become immediately apparent, as chroniclers, historians, clergy, poets, and playwrights dismiss her as a witch, exclude her entirely from narratives, rearrange events, omit her triumphs, or give credit to her male counterparts. Then there are the seemingly endless attempts at painting Joan as promiscuous, to “demystify a heaven-sent virgin.”

Throughout this historiography, Orgelfinger compares how each writer also wrote of other female warriors; available examples included Ælfleda of Mercia (died 918) and the Empress Maud (1102-1167). This approach demonstrates that “consistent in all eras is an unwillingness to uncouple a woman’s leadership from her identity as a sexual being.” The “association of a woman warrior with unnatural magic,” Orgelfinger writes, “clearly did not originate in the career of Joan of Arc.” By the Enlightenment, writers may acknowledge Joan’s successes but cannot accept her cross-dressing or acting in a man’s role — behaviors opposed to more “suitable” roles for women in the military (e.g., laundry), demonstrating that the manifestations of sexism today and in the 18th century are not far removed.

Divergent opinions persist throughout, such as in the writing of Edward Hall (1497-1547), who compared Joan’s accomplishments with those of other historical women, proclaiming that he would never think of “this female warrior” as anything other than “a noble captain,” even if he “ascribed Joan’s virginity to her ugliness.” More progressive, John Speed (1551 or 1552-1629) believed the English would have spared her had she not been French. Peter Heylyn (1599-1662) defended Joan “not merely against witchcraft and sorcery but against those who would downgrade her achievements merely on account of her sex.” Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832) wrote the English burned her “to their eternal disgrace.”

Orgelfinger believes the most succinct summary of views comes from Thomas Fuller (1608-1661), who tells us, “Some count saint, and some count witch; Some count man, and something more; Some count maid, and some a whore.” Today, opinions on Joan still vary among saint, military commander, myth, or mere propaganda piece for the French. Readers may grapple with how 400 years of conflicting English perspectives influence our own beliefs on Joan as more than a golden statue.

Scott Manning (@warpath, scottmanning.com) from Upper Darby holds a master’s in history and serves on the board of the Mid-Atlantic Popular & American Culture Association.