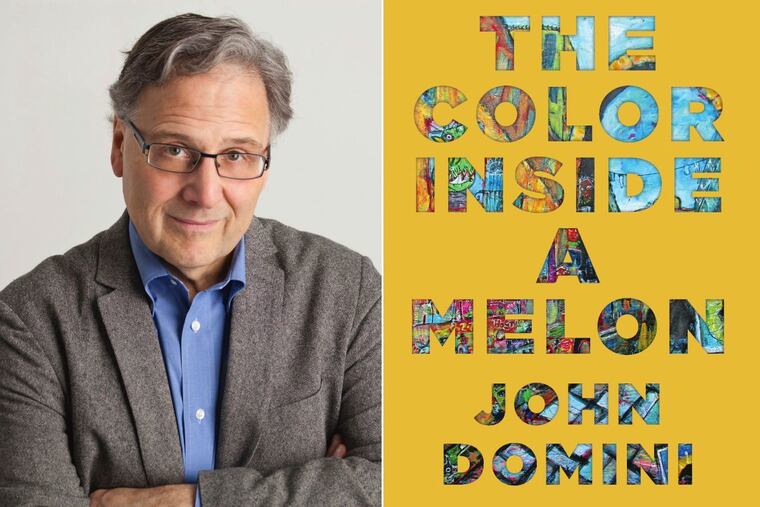

‘The Color Inside a Melon’ by John Domini: A genre-busting noir with trad roots

This spry, wise novel stretches the boundaries of crime fiction. Our central figure is a Somali emigrant to Naples, who assimilates but also plays detective to solve a murder. Assimilation, immigration, and cultural dissonance thus get folded into a very intelligent entertainment.

The Color Inside a Melon

By John Domini

Dzanc. 344 pp. $16.95

Reviewed by Mark Athitakis

John Domini’s sage, genre-tweaking fourth novel, The Color Inside a Melon, is in some ways an old-fashioned noir. It’s set in a city with a seedy underbelly — Naples. There’s a corpse, of course — in this case that of a Somali migrant. There’s a crime that speaks to the darker recesses of humanity — rumors of a snuff film made at a dance party. Most essentially, there’s a would-be detective who is out of his depth but who can’t leave well enough alone.

The ersatz gumshoe is Aristofano, aka Risto, another Somali refugee who’s planted roots in Italy after escaping his homeland’s violence 15 years earlier. That’s long enough to establish himself as the owner of a prominent gallery bearing the evocative, biblical name of Wind & Confusion. But he’s also been around long enough to know his existence there will always be suspect and provisional. “What did the police care about a brother cut to ribbons?” he thinks. If he wants the case of a dead black man solved, he’ll have to do some of the legwork himself.

The cross-cultural vibe is just one way Domini’s novel isn’t so old-fashioned. The narrative has its requisite share of mobsters, cops, and bloodshed, but for Domini these are mainly lenses through which to explore Risto’s sense of displacement and belonging. Anti-immigrant blogs agitate against African refugees as “the virus that could bring down all of Europe,” and anybody who wants to stay in the country faces, if not outright violence, at least casual bigotry and mountains of paperwork. (Risto escaped the problem, at least somewhat, by marrying an Italian woman.)

So Melon functions as much as an assimilation novel as it does as a noir. But it is rhetorically offbeat as well. Domini is an enthusiast for experimental and postmodern eminences like John Barth and Steve Erickson, writers whose every sentence was microscopically tweaked for meaning and resonance. In the wrong hands, postmodern paragraphs can read as though they require a pickax to penetrate, and the plot in Melon can get dense, as Risto experiences hallucinatory visions that put halos around the heads of people in photos, a “mystic Photoshop” he often noodles over.

But as postmodern crime yarns go, this one is pretty spry, and especially well-turned when it comes to Risto’s struggle to reconcile the crime he’s solving with the violence he witnessed in his youth. The "thug economics" of contemporary Naples evokes the worst of Mogadishu, where "Risto got to see what a skull looked like several days after the machete split it." The novel’s title is a deliberately queasy evocation of the image, a violent take on the romantic idea that we’re all the same on the inside.

Such Pollyannaish notions are worth attacking, Risto figures, because if we’re all the same on the inside, our insides could use some improving — especially when it comes to migrants. Naples is “a city that gets older but never gets anywhere,” he tells his wife at one point. “Everybody stays in the piazza. Everybody sits around the fire telling the old stories.” Domini’s novel is determined to wrench the noir — and us — out of well-worn ruts.

Mark Athitakis, a critic in Phoenix and author of “The New Midwest,” wrote this review for the Washington Post.