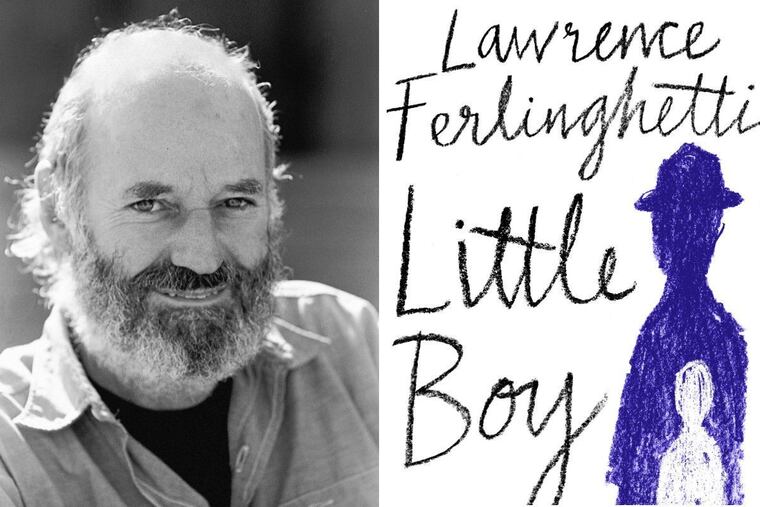

At age 100, Lawrence Ferlinghetti lets it rip in ‘Little Boy’

Wide-ranging, unbuttoned, this Beat Generation hero speaks of his own life and everything else, in jokey, crusty, often lyrical pages of reminiscence and wisdom. It's a wild ride but worth it.

Little Boy: A Novel

By Lawrence Ferlinghetti

Doubleday. 192 pp. $24

Reviewed by John Timpane

Little Boy calls itself a novel, but of course it’s not. Others are calling it an “autobiography,” and some of it is, but much else, well, who knows?

More certain is this: On March 24, poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti turned 100, and here we have Little Boy. Ferlinghetti has quite a place in American literary history. He cofounded the bookstore City Lights in San Francisco, a little store that has changed the course of both poetry and bookstores. For it was also a press, and in 1956, it published Allen Ginsberg’s Howl and Other Poems, the opening salvo of the Beat Generation. That led to Ferlinghetti’s arrest, charges of indecency, and a landmark First Amendment trial that Ferlinghetti won. City Lights also published Ferlinghetti’s own wildly popular A Coney Island of the Mind, one of the few American poetry collections to sell more than a million copies. (Another one by now is Howl, which still sits next to the cash register at City Lights. When you go there, pick up a copy.)

I am calling Little Boy a single, long prose poem. It does start autobiographically, with the emigration of his ancestors from the Virgin Islands, but soon it spools into a movie of the mind.

He pictures himself sitting in “this existentialist cafe on the left coast of this country, watching reality pass by with a wild eye to inscribe on my [hear all the long i sounds] brainpan a tale of sound and fury signifying everything.” Ferlinghetti lets it rip, going where he will go, in unpunctuated free-association pages of literary allusions, curmudgeonly grumbles, wisdom, and outbursts of beautiful language. In this wild ride, reminiscences of Sartre (of whom he thinks not much), Henry Miller, the 1960s, and lovers past collide with cosmic thoughts. “Yeah just think of it,” he writes with no commas, “isn’t consciousness itself the ultimate god of all of us for as long as consciousness lives we live and the only other god that rules everything is great god Sun.”

The often crusty author reminds us he is an old guy (“the inside gets harder and the outside gets softer”) near the end, as is our species and planet: “The world’s an ice cream melting down and we are tiny animals sprinkled on it.” Surrounded by folks plugged into cellphones at his cafe, he thinks: “[H]ow can I escape this boatload of somnolent cafe sailors on a cruise?”

In the meantime, those explosions can be lovely. Especially ineffable, especially bravura is a passage beginning “Oh Endless.” It runs for pages and is by itself worth the price of the book:

Oh endless the splendid life of the world Endless its lovely living and breathing its lovely sentient beings seeing and hearing and thinking laughing and dancing sighing and crying though endless afternoons endless nights drinking doping talking and singing with endless lively conversations over endless cups of coffee in literary cafes on rainy mornings

Read it aloud. It’s a hymn of love to life, which seems so big and permanent to us who live it, and does contain, for Ferlinghetti, the “crystal moments,” sweetest of the sweet, best of the best. All I can say is, Little Boy done good and is still doing it.