Margaret Thatcher’s last stand | Book review

The third volume of Charles Moore's authorized biography covers the years from Thatcher's triumphant reelection in June 1987 to her fall, decline, and death in 2013.

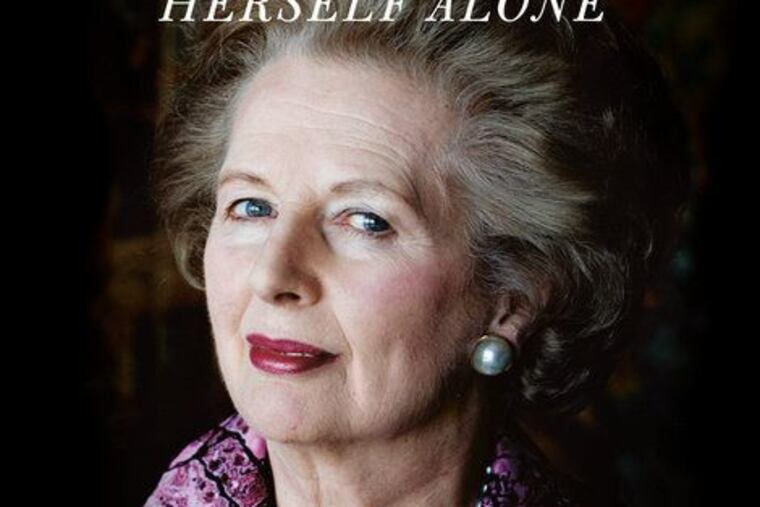

Margaret Thatcher: Herself Alone: The Authorized Biography

By Charles Moore

Knopf. 1,006 pp. $40

Reviewed by Elaine Showalter

When the second volume of Charles Moore’s biography of Margaret Thatcher came out in 2015, she had two indisputable claims to preeminence: She was the only woman to have been prime minister of the United Kingdom and the most reviled political figure of modern British history. Now Theresa May has joined Thatcher on that short list of female PMs, and Tony Blair, David Cameron, and a fast-moving Boris Johnson have knocked her off the top of the hate list. It seems long ago that she was wielding her symbolic handbag of power in Parliament and bestriding the world stage as the Iron Lady of a still-great peacetime Britain.

Yet Thatcher is one of a tiny number of women in history to deserve and receive the accolade of a three-volume biography. Moore’s massively researched, elegantly written, and admirably balanced book, covering the years from her triumphant reelection in June 1987 to her fall, decline and death in 2013, does justice to her courage and complexity. True, his minutely detailed account of Tory politics, with its Jacobean skirmishes and fraught cabinet reshuffles, will probably mean little to most American readers.

But Thatcher’s final term encompassed many events of trans-Atlantic and global significance. Despite her reputation as rigid and unfeeling, she took progressive, empathetic stands on many issues, often ahead of her party. Trained as a scientist, she took an early interest in discussions about AIDS and talked about the need for international conferences on climate change.

She supported free speech. Although Salman Rushdie belonged to a group of British writers ferociously opposed to Thatcher and had created a character in his novel The Satanic Verses called “Mrs. Torture,” when the Ayatollah Khomeini declared a fatwa on Rushdie for blasphemy, her government gave him full police protection, moving him among 57 safe houses in five months. After Khomeini’s death in June 1989, they helped him negotiate with the Iranian government to get the fatwa lifted. (Although never resolved, the threat became dormant, and after Thatcher’s death Rushdie expressed some gratitude that she had offered him unquestioning support.)

She worked with white South African leaders to end apartheid, and Nelson Mandela's release was a high point of her term. In his first official visit to Downing Street on July 4, 1990, they talked for so long that the press waiting outside started to chant "Free Nelson Mandela!" Although the Brexiteers claim her as their Euroskeptic patron, it's unclear how she would have voted. She was concerned about a centralized bureaucracy run out of Brussels and a European single currency, and she was strongly opposed to German reunification, but she also believed that "Britain was part of European civilization" and that its destiny was "in Europe, as part of the Community."

But Thatcher’s extraordinary run came to an end with a series of disasters and misjudgments at home, especially the hugely unpopular poll tax. On Nov. 22, 1990, she stood down. She was a vigorous 65, and the loss of status was an abrupt transition, Moore writes, for which she was “unprepared emotionally, domestically, financially and practically.” She had no permanent home, office or staff, and a meager income from government pensions. Her husband, Denis, had plenty of money but hadn’t paid a bill himself since they moved to Downing Street. Out of sync with modern technology, fuming about those who had forced her out, she had to make money, set up a household and find a new role. She made lucrative speaking tours, wrote her memoirs, and soon entered the House of Lords as Baroness Thatcher.

In 2001, she had a few small strokes, and some people noticed a mental decline. Denis died suddenly in 2003; her dearest ally, Ronald Reagan, died of Alzheimer’s in 2004, and, suffering from early dementia herself but superbly dressed and coiffed by her devoted household team, she attended the funeral, where her prerecorded eulogy protected her from embarrassing slips. Moore presents these last years as particularly sad, calling her “The Lioness in Winter.” Her adult children, Mark and Carol, gave her more worry than help, and she could never get the hang of country-house weekends. “She played no games or sports,” notes Moore, and “dressed with intimidating formality.” In her retirement, she was like a woman “unwillingly divorced” and “isolated in a man’s world.” These feminizing metaphors trivialize her strength and disregard comparisons to her male peers, including Reagan and French President François Mitterrand, massively protected in retirement and decline.

Moore is aware of the sexism and overt misogyny Thatcher suffered. He points out that her ability to establish solid relationships with world leaders was often described as flirtatiousness and infatuation, rather than thorough preparation. When she hosted Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev in April 1989, the Soviets said she looked at him with “sheer rapture and adoration.” Yet Moore himself too often casts her in a stereotypically feminine, besotted role, calling her “girlishly effusive about Reagan” and as awkward when she met with his successor, George Bush, as “a girl on a new date after many happy years with her previous boyfriend.” He tends to underestimate her self-confidence and exaggerate her dependence on male courtiers. In his epilogue, he calls her “an icon, without rival, of female leadership” but not, despite the controversies, a model of political leadership in general.

Thatcher died in April 2013 and chose not to have a state funeral to which heads of state were invited. President Barack Obama sent a message saluting her as “one of the great champions of freedom and liberty.” But an era of dignity and decorum was falling away. Donald Trump, then just a New York real estate developer, was not invited either, but he seized the opportunity to insult his perceived rivals, tweeting that it was terrible that Obama, Joe Biden, and John Kerry did not attend.

In the brawling pandemonium of Washington and Brexit, I hope Thatcher’s gifts of discipline, intelligence, and dedication may finally be recognized beyond the bounds of gender.

Elaine Showalter is a professor emerita of English at Princeton University. She wrote this for the Washington Post.