Greta Thunberg’s family memoir sends an urgent message to us all | Book review

"Our House Is on Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis" focuses on the harrowing years that preceded the Nobel Peace Prize nominee's time in the spotlight as an environmental activist.

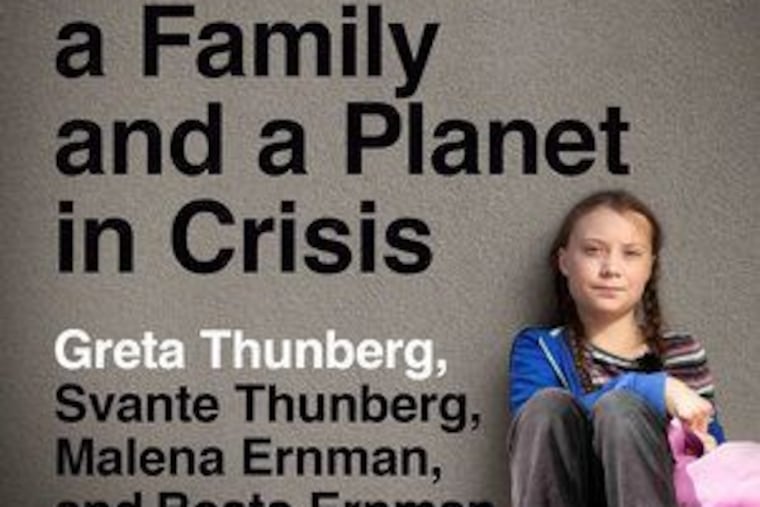

Our House Is on Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis

By Greta Thunberg, Svante Thunberg, Malena Ernman, and Beata Ernman

Penguin Books. 288 pp. Paperback, $17

Reviewed by Zibby Owens

I didn’t think I could feel more worried about the world. Turns out, I can — and we must.

Our House Is on Fire: Scenes of a Family and a Planet in Crisis is the story of Greta Thunberg’s family, focusing on the harrowing years that preceded the Nobel Peace Prize nominee’s time in the spotlight as an environmental activist. It’s both an intimate personal story and a call to action. Its message is hard to ignore.

"This story," Greta's mother, Malena Ernman writes, is "about the crisis that struck our family." But, she adds, "above all it's about the crisis that surrounds and affects us all. The one we humans have created through our way of life: beyond sustainability, divorced from nature, to which we all belong. Some call it overconsumption, others call it a climate crisis. The vast majority seem to think this crisis is happening somewhere far away from here, and that it won't affect us for a very long time yet. But that's not true. Because it's already here and it's happening around us all the time, in so many different ways. At the breakfast table, in school corridors, along streets, in houses and apartments. In the trees outside your window, in the wind that ruffles your hair."

The book, which came out in Sweden in 2018, feels portentous in so many ways.

The story is told in 108 quick scenes, each one a purposeful moment in the narrative that ends with Greta's groundbreaking role in the climate movement.

Everyone in the family — parents Malena and Svante Thunberg, Greta, and her younger sister, Beata Ernman — contributes, but Our House Is on Fire is mostly written from Malena’s perspective. And really, this book will hit mothers hardest. As a mother of four myself, I know all too well that nothing makes a parent feel more helpless than seeing a child in pain and being powerless to do anything about it. That’s what Malena experienced and what so many other parents continue to face today.

Malena, a renowned opera singer who says she unexpectedly won the American Idol of the Nordic countries, called Melodifestivalen, writes in depth about the chaotic and terrifying experience of taking care of Greta as she struggled with mental health issues. Greta, who for a time refused to eat and speak, was eventually diagnosed with an eating disorder, selective mutism, and Asperger’s. But the path to obtaining those diagnoses and treating them included moments when, her mother writes, “the gates of hell crack[ed] open” revealing a “heavy boundless darkness” of pure fear.

By the summer of 2016, it isn't only Greta suffering but Beata, too. Years later, Beata diagnoses herself with misophonia, which presents as an inability to cope with sound. But no one knows this for a while. Beata exhibits compulsive behaviors, can't be around other people, and only finds release in dance.

» READ MORE: The real dirt on Oprah Book Club's "American Dirt."

In the midst of the two girls' struggles, a summer renovation in their building causes the family to "lose its footing." Malena writes, "We scream. We kick down doors. We scratch. We pound walls. We wrestle. We cry. We ask for help and we somehow endure." Malena starts having panic attacks; she passes out before an opera performance.

By the time Greta starts crusading for action on climate change in August 2018, we’re rooting alongside Malena to just find something to bring the girl some relief. This is what does it. The only time Greta speaks to anyone outside of her immediate family or eats more than her limited repertoire of foods is when she goes on strike outside Sweden’s parliament and starts speaking to journalists, sharing the statistics and facts about the current climate emergency. Her brain can’t comprehend why, if this is the case, no one is reacting as they logically should be by mobilizing to solve the problem. She is at a loss. And in this confusion, she finds herself. She tries Thai noodles. She speaks in public. She even smiles.

When someone in the crowd asks her father if he's proud of her, he responds, "Proud? No, I'm not proud. I'm just so endlessly happy because I can see that she's feeling good."

For many people, sharing such details might be difficult, might even be a source of shame. But for this family, it is the opposite: “This story is way too humiliating for all involved — and that’s why I have to tell it,” Malena writes. The family’s decision to do so, she adds, came “after considerable deliberation.” Perhaps, she says, “it should have been saved for later. Once we had more distance. Not for our sake, but for yours.” But, she implores us, “we don’t have that kind of time. To have a fighting chance, we have to put this crisis in the spotlight right now.”

Greta’s parents don’t come off as puppet masters manipulating their daughter to fight their battles. They are like so many of us who would do anything to help our children feel better.

There’s a lot of discussion about the term “hope” in this book, that people won’t bother consuming facts and figures without some “hope” attached. Greta thinks hope is too optimistic in the midst of a catastrophe. First, we have to put out the fire, then we can draw on hope to cope. (Proceeds from the book’s sales will go toward a foundation that gives to environmental groups.)

Malena writes: “We can’t solve a crisis situation until we treat it as a crisis situation. ... It’s the crisis itself that is the solution to the crisis. Because in a crisis we change our habits and our behaviour. In a crisis we are capable of anything.”

Reading this book during the novel coronavirus outbreak, these words feel especially apt.

Owens is host of the podcast “Moms Don’t Have Time to Read Books.” She wrote this for the Washington Post.