‘Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light’: Essays on art by a poet with a keen eye

Witty, engaging, without the hauteur assumed by so many art critics, this collection of essays on everyone from Bronzino to Picasso, as well as several modern and postmodern female artists, is an engaging, wondrous read, with attentive, sometimes thrilling accounts of what the artworks actually do.

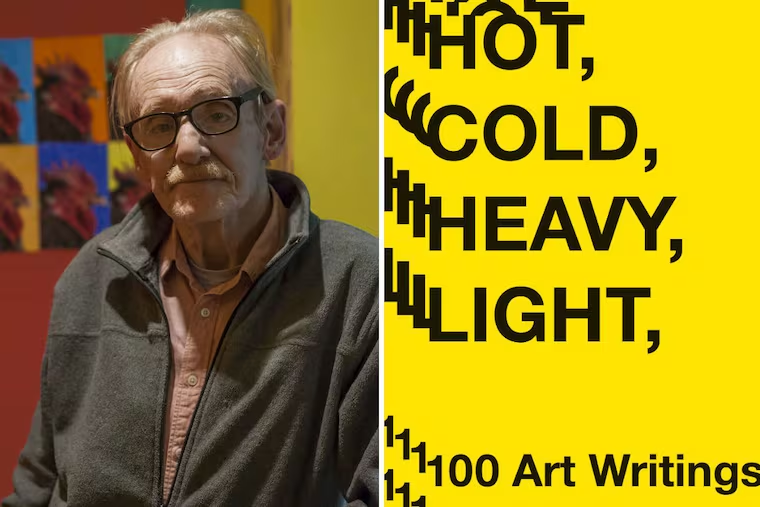

Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light

100 Art Writings 1988-2018

By Peter Schjeldahl

Abrams. 368. $28

Reviewed by John Timpane

Maybe you’ve enjoyed Peter Schjeldahl (pronounced SHELL-doll) as an art critic for the New Yorker, where he’s written since 1988, or before that, when he wrote for the Village Voice and 7 Days. He is a practicing poet, and the poet’s specificity and clarity are his biggest assets. He’s also witty, and mostly, or at least usually, without the unearned hauteur that so many art critics seem obliged to assume.

Hot, Cold, Heavy, Light assembles 100 essays from across three decades of writing. Begin with “Credo: The Critic as Artist: Updating Oscar Wilde,” in which Schjeldahl lays out his personal philosophy of criticism, one that “promotes intelligence and energy in culture … while making the exercise as little forbidding and boring as possible. It posits pleasures of the text as a rightful expectation of readers. It is autobiographical.” That means he often brings himself into the discussion; no fake objective stance here. In an early essay on Matisse, he snipes, “I still don’t like him,” and in a later one he admits, oh, heck, “now I succumb.” He tells us he never got the mystique of Greek sculpture — in an essay that ends up cheerleading for it.

But let’s go to the Barnes and look at The Postman (Joseph-Étiernne Roulin) by Vincent van Gogh. This calls forth from Schjeldahl one of his marvelous descriptions of the artist’s work: the painting

is keyed to a clash of fresh blue in the uniform and moody green in the background. Variously spiced browns in Roulin’s beard, forthright yellow-gold in the buttons, and rust-red pinks in the flower shapes keep your eye jumping. … Roulin’s flesh is rendered in medieval-ish green and red hatchings.

Makes you want to walk over to the Barnes and gaze at it again.

In a drawing by Venetian painter Agnolo Bronzino, “Within the lines, fabulously deft anatomical details, in hatched and smeared shadings, capture musculature and voluptuous flesh.” This is not only incredibly beautiful writing, but try reading it aloud — it breaks the jaw with pleasure. Stunned at Prophet, a 1435 or 1436 sculpture by Donatello, he writes: “You sense from the hands, arms, neck, and one bare shoulder, and the sandaled feet, the whole of a gaunt, sinewy body, which you all but smell.”

He also has much serious work to do. He wants to tell us exactly why Shepard Fairey is “energetic but unoriginal,” why Goya is a disappointment, why Degas is a misogynist and a sadist, and why Francis Bacon “is my least favorite great painter of the 20th century.” He also wants to share surprises, including that Picasso’s sculptures between 1927 and the mid-1930s “belong in the first rank of sculpture since ancient times.” He is terrific with the short summing-up that nails an essential aspect of the artist. Of Alice Neel he writes: “Art was not a refuge for her. … It was her life lived by other means, in which she enjoyed some moment-to-moment control.” “Seeing an unfamiliar painting by Rembrandt,” he writes elsewhere, “is a life event, fresh data on what it’s like to be human.”

One glory of this book is the way Schjeldahl writes about female artists. Essays on Neel, Laura Owens, and Laura Harrison are among the book’s best. In a very sensitive essay on Agnes Martin, a great artist and a troubled mind, her brilliance moves him to say: “The relation of Martin’s mental illness to her art seems twofold, combining a need for concealment and for control … with an urge to distill positive content from the oceanic feelings she couldn’t help experiencing.”

The best single thing in this book is “The Ghent Altarpiece,” in which Schjeldahl discusses the elaborate efforts to preserve and protect the masterwork (thought to be largely by Jan van Eyck), and in which he rises to some of his best description of “hands that touch and grip with tangible pressures, masses of hair given depth and definition by a few highlighted strands.” He then adds: “Overall, the pictures generate a sweet and mighty visual music.” Much the same is true of this gorgeously yet precisely written collection.