‘Soulless’ by Jim DeRogatis: R. Kelly’s ‘problem’ — and injustice to black women

The longtime pop critic of the Chicago Sun-Times tells the story of a star with a reported predilection for underage females. The story is persuasive and angering -- especially the racially insensitive failure of the system to punish crimes against black women.

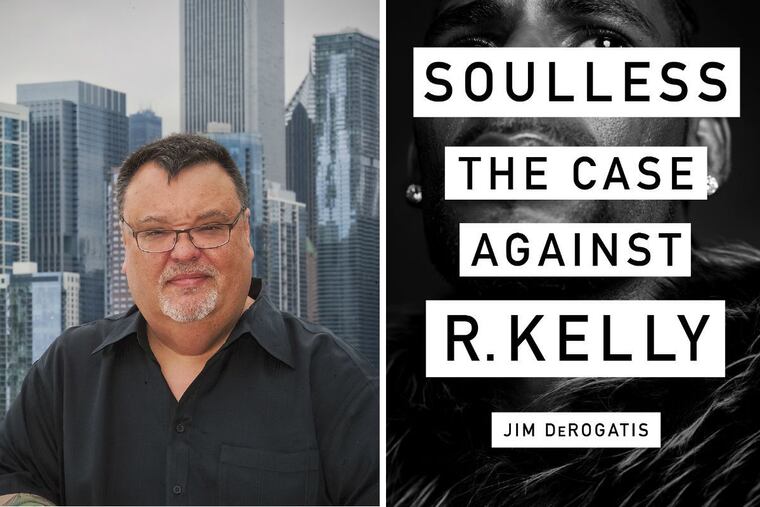

Soulless

The Case Against R. Kelly

By Jim DeRogatis

Abrams. 288 pp. $26

Reviewed by Solomon Jones

“Robert’s problem — and it’s a thing that goes back many years — is young girls.”

That line from an anonymous fax, sent to a music critic at the Chicago Sun-Times, is at the center of Jim DeRogatis’ Soulless: The Case Against R. Kelly. The book, gleaned from years of dogged reporting, is built upon names and dates, court documents and interviews, videotapes and faxes.

Using those time-honored tools, DeRogatis, longtime pop music critic for the Sun-Times, deftly illustrates Kelly’s alleged crimes against young girls, and does so while wielding facts with the mastery of a prosecutor.

However, the facts are not the most alluring aspect of DeRogatis’ work. The appeal of this book is the emotion that winds between the evidence, binding facts and feelings the way tendons bind muscle to bone. We empathize with Kelly as we learn of his rise from adversity. We experience his alleged victims’ pain as they share their horrifying stories. We internalize the rage of a community that couldn’t protect its most vulnerable members. But for those of us who know Kelly’s music, this story is one that transforms us, much as it did DeRogatis.

Through the mid-’90s, DeRogatis “followed R. Kelly’s burgeoning career with the pride of a hometown journalist and critic who’d been there almost from the start, as well as, I’ll admit it, a fan, albeit one with reservations.”

Then the fax arrived, and as DeRogatis and fellow reporter Abdon Pallasch uncovered documents and interviewed witnesses, DeRogatis moved from fickle fan to dogged detective.

Much of the resultant narrative is built on aspects of the story that are well-known, thanks to Surviving R. Kelly, the heart-wrenching six-part documentary featuring the singer’s accusers that aired on Lifetime earlier this year. However, as the author repeatedly reminds us — sometimes annoyingly — DeRogatis and Pallasch initially reported much of R. Kelly’s story in the Chicago Sun-Times.

The facts that DeRogatis and Pallasch discovered in their reporting bore out the assertions in the fax.

In 1994, Kelly married the R&B star Aaliyah, who was 15 at the time of their nuptials. And after videos emerged of Kelly’s alleged sexual exploits with underage girls, Kelly was charged with 21 counts of child pornography. Six years later, in 2008, he was acquitted on all counts. Those are the facts, but it is emotion that drives this book, and DeRogatis excels at finding the voices that evoke an emotional response.

One voice he comes back to repeatedly is that of Demetrius Smith, a former member of Kelly’s entourage, who explains in this passage how Kelly’s alleged sickness manifested itself:

Night after night, the studio or the green room backstage might fill with twenty beautiful women. Nineteen could be 21-year-olds, but Kelly consistently focused on the self-conscious teen standing alone in the corner, staring at her feet, too shy to talk. “He likes the babies, and that’s the sickness,” Demetrius Smith confirmed. “He can control her, and she don’t know no better.”

Tracy Sampson, one of Kelly’s alleged victims, delves deeper into the way Kelly allegedly manipulated underage girls. In an interview with the Washington Post that DeRogatis quotes, Sampson said:

“He makes you feel like he’s a wounded puppy, like he’s hurt so deeply, that there’s good there, he just can’t get it all out. Being so much older [now], I see how wrong stuff was and how ultimately gross and pedophile-ish it was, but that’s something you have to have your adult brain to process.”

As a reader, the quotes from Sampson and other alleged victims made me feel sympathy for the crimes they said they’d endured. But as a black reader, the stories of these black women moved me to anger. In my view, the allegations against Kelly could never have gone unchecked and unpunished for so long had Kelly’s accusers been white. Given that the vast majority of them were black and brown, the wheels of justice moved at a snail’s pace, even with video evidence of Kelly’s alleged behavior.

DeRogatis writes that he shared that anger, saying that it “infuriated and sickened” him that so many music critics gave Kelly a pass on the charges against him while fawning over his music.

“I believe we should always consider the context of the art,” DeRogatis writes, “and we can’t ignore or forgive significant moral wrongs at its core — racism, sexism, misogyny, homophobia or worse.”

I agree. But the failure of the system to punish Kelly’s alleged behavior is primarily about racism, not those other social ills. If DeRogatis’ book has a shortcoming, it is that it does not drive that point home forcefully enough.

However, Soulless does a marvelous job of giving voice to those who say they’ve lived this story. Perhaps, due to DeRogatis’ thorough reporting in this book, they will live to see the justice they seek.