Emma Donoghue set her new novel, ‘The Pull of the Stars,’ in the 1918 pandemic | Book review

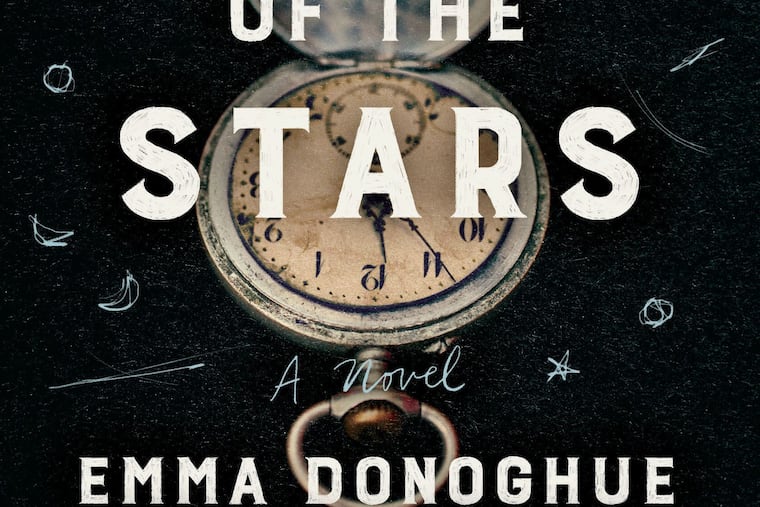

The Pull of the Stars

The Pull of the Stars

By Emma Donoghue

Little, Brown. 297 pp. $28

Reviewed by Wendy Smith

Set at a Dublin hospital in the grip of the 1918 flu pandemic, Emma Donoghue’s 11th novel, The Pull of the Stars, grimly foreshadows present-day circumstances. “If In Doubt, Don’t Stir Out” warn posters affixed to streetlamps; overwhelmed hospital staff are bedding patients on the floor, and stores have run out of disinfectant. Yet the pandemic is simply a backdrop for Donoghue’s searing portrait of women’s lives scarred by poverty and too many pregnancies in a society that proclaims, “She doesn’t love him unless she gives him twelve.” The Catholic Church is called to judgment as well, for its brutal treatment of unmarried mothers and their offspring. From these dark materials, Donoghue has fashioned a tale of heroism that reads like a thriller, complete with gripping action sequences, mortal menaces, and triumphs all the more exhilarating for being rare and hard-fought.

Her hero is Julia Power, a maternity nurse striving to save the lives of pregnant women at even greater risk than usual during labor and delivery because they have the flu. She has to care for them in a converted supply room barely big enough for three cots. Equipment and personnel are both scarce, due to the pandemic and the world war that has taken many doctors to the front. When Julia arrives at work on Oct. 31, 1918, she's saddened but unsurprised to learn that one of her patients died overnight. Flu-induced pneumonia is the immediate cause, but if she'd been completing the paperwork, Julia thinks bitterly, "I'd have been tempted to put: Worn down to the bone. Mother of five at twenty-four, an underfed daughter of underfed generations … this flu had only tipped her over."

Julia has little use for the pious resignation of sanctimonious night nurse Sister Luke, though she’s grateful when the nun grudgingly sends her a desperately needed aide. Bridie Sweeney is unqualified and uneducated but quick to learn, and Julia warms to her as they deal with three harrowing deliveries (sources of the aforementioned action, menaces, and triumphs). Squeamish readers may blanch at Donoghue’s graphic accounts of childbirth, with fatal results in two cases, but the messy particulars underscore Julia’s angry rejoinder to an orderly who argues that women shouldn’t be allowed to vote because they “don’t pay the blood tax” that soldiers do. “Look around you,” she snarls, indicating one patient in hard labor and another who has borne a dead baby. “This is where the nation — every nation — draws its first breath. Woman have been paying the blood tax since time began.”

Many novels depict the brotherhood of men at war. Donoghue celebrates the sisterhood of women bringing life into the world and those who help them along this perilous journey. She stacks the deck slightly by making the hospital’s only capable doctor female, but Kathleen Lynn was an actual person, a member of Sinn Fein released from jail after the Easter Uprising so she could combat the flu. As she has in such previous historical novels as Life Mask and Slammerkin, Donoghue makes deft use of real-life figures for her fictional ends. In addition to her crucial role in saving several patients, Dr. Lynn gives the novel its central metaphor when she explains to Julia that the word influenza comes from the medieval Italian belief that the influence of the stars made people ill.

“As if, when it’s your time, your star gives you a yank,” Bridie remarks when Julia passes on that information, with blunt lyricism characteristic of Donoghue’s eloquent, no-frills writing style. The two women are trading confidences on the hospital roof, getting some air after two grueling days have made them friends. Bridie is one of the abused “boarders” at Sister Luke’s convent, unwanted or illegitimate children left to be beaten, starved, and used as enslaved labor in the same repressive, patriarchal system that consigns married women to endless childbearing.

This system oppresses men and boys as well, Donoghue acknowledges. Julia's brother Tim returned from war shell-shocked and mute; the infant boy whose unwed mother died during delivery is judged by Sister Luke as "unlikely to thrive … his kind generally have more than one hereditary weakness." But the novel's focus is on the hard-won strength of its female characters, especially Julia's fierce dedication to her patients and Bridie's cheery enjoyment of each simple pleasure denied her at the "Motherhouse." Their tender relationship stands at the novel's heart and adds poignant satisfaction to Julia's final faceoff with Sister Luke.

As in her best-known work, the deservedly megaselling Room, Donoghue infuses catastrophic circumstances with an infectious — but by no means blind — faith in human compassion, endurance, and resilience. The Pull of the Stars closes with a final surge of plainspoken poetry, as Julia looks toward the future while walking “through streets that looked like the end of the world.”

Smith is the author of “Real Life Drama: The Group Theatre and America, 1931-1940.” She wrote this for the Washington Post.