‘The Three Mothers’ honors the women who made Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin | Book review

Anna Malaika Tubbs writes about about women who gave birth to extraordinary men and who “have been … presented as footnotes that are out of context."

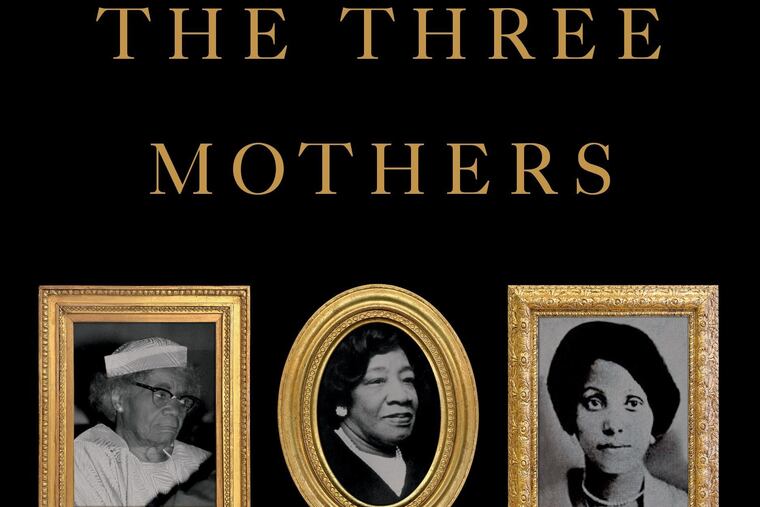

The Three Mothers

By Anna Malaika Tubbs

Flatiron. 229 pp. $28.99

Reviewed by Lisa Page

Motherhood is said to be its own reward. You learn to give of yourself, and this will stretch you, as a person. But you may also learn to put yourself in the background, which will shrink you — and even make you disappear.

History does this to us anyway, argues scholar Anna Malaika Tubbs. Black women in particular are largely erased from the American historical trajectory — marginalized, at best. Tubbs tries to remedy this with a new book about women who gave birth to extraordinary men, women who “have been hidden not only behind their sons but also behind their husbands, … presented as footnotes that are out of context.” In The Three Mothers: How the Mothers of Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, and James Baldwin Shaped a Nation, Tubbs resurrects these women and shows them to be players with agency and influence.

The three have much in common: They were born within a few years of one another; they all married men trained in the church; their lives spanned the 20th century; all three outlived their sons. And yet they were very different from each other.

Louise Langdon Little, who became the mother of Malcolm X, was Caribbean and biracial. Born in 1897, “the exact details of her conception have been lost to history,” Tubbs notes, but it is believed that her mother was raped by a white man. Sadly, this was not uncommon, Tubbs reminds us: “The effects of slavery … the constant control of Black women’s bodies through sexual violence, was universal, far after emancipation.”

Louise migrated to Canada in 1917. She met Earl Little, a Baptist minister, at a Universal Negro Improvement Association meeting. The UNIA was founded by activist Marcus Garvey, a fellow West Indian. Louise and Earl married and worked as field organizers, promoting Garvey’s call for Black independence in American cities. The Littles had seven children together. Louise served as branch secretary and wrote for the Negro World newspaper and spoke at least three languages: English, French, and Patois. Louise Langdon Little died in 1989 at age 92.

Emma Berdis Jones Baldwin, who became the mother of James Baldwin, was born on Maryland’s Eastern Shore in 1901. She left the Jim Crow South for Philadelphia, and later, New York, during the Great Migration. In 1924, she had a baby, out of wedlock, named James Arthur Jones. She married David Baldwin, a preacher in the Pentecostal tradition, and the two of them had eight more children together.

Of these three women, Emma “had the least in terms of money and education,” Tubbs writes. Her husband was paranoid and abusive and had trouble supporting his family. Emma committed him to a mental institution, while she was pregnant with their ninth child, and he died shortly thereafter, in 1943. Emma Berdis died in 1999 at age 95.

Alberta Williams King, who became the mother of Martin Luther King Jr., was born in Atlanta in 1904. Her family had resources. Her father, the Rev. Adam Daniel Williams, was one of the founders of the Atlanta chapter of the NAACP and the pastor of Ebenezer Baptist Church. Alberta was the most educated of the three mothers, attending Spelman Seminary, the Hampton Normal and Industrial Institute, and Morris Brown College. She married Baptist preacher Michael King, and they had three children together.

Alberta was not allowed to make the most of her education. “At the time, there was also a law that kept married women from teaching,” writes Tubbs. “This ‘marriage bar’ … lacked any logic; it was simply in place to restrict middle-class, educated women and it was not fully terminated until 1964 with the passing of the Civil Rights Act.” Alberta focused, instead, on tutoring her husband, establishing women’s coalitions, and directing the children’s choir. Alberta King died in 1974 at age 84.

All three women lived through the Harlem Renaissance, the Great Migration, the Great Depression, and the civil rights movement. They knew the consequences of the women’s suffragist movement, when white suffragists rejected Black women in 1920. They walked in the shadows of other great Black women, Tubbs asserts, including Harriet Tubman, Ida B. Wells, Rosa Parks, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Mamie Till, Emmett Till’s mother. They endured sociologist Edward Franklin Frazier’s assertion that Black women in the 1930s resisted subordination and male authority, “emasculating their husbands and failing to fulfill their womanly duties.” They were subject to insulting distortions of Black people, including the “Mammy,” the “Jezebel,” the “Pickaninny,” and the “Welfare Queen,” in popular culture. They survived white sociologist (and future U.S. senator) Daniel Patrick Moynihan’s 1965 claim that households run by Black mothers were inadequate compared to white families.

Each woman endured tremendous personal loss. The Little marriage was tumultuous, and Earl Little was fatally struck by a streetcar in 1931 under circumstances his son and others considered suspicious. Louise was forced to go on welfare, certified insane, and committed to the Kalamazoo State Hospital for more than 25 years. She was released just before the assassination of Malcolm X. Alberta lost not one but two sons: After Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination in 1968, her other son, A.D. King, drowned the following year. Emma’s son, James Baldwin, became an amazing artist and activist and lived into the 1980s but died of cancer of the esophagus.

In the face of racism, sexism, and tremendous violence, these three mothers survive. They are honored, in these pages, as the extraordinary women they were, in their own right. This ambitious book reframes African American history, supplying the female Black experience as a much-needed perspective.

Lisa Page is coeditor of “We Wear the Mask: 15 True Stories of Passing in America.” She is an assistant professor of English at George Washington University. She wrote this review for the Washington Post.