Two accounts of Watergate remind readers: No one knew how it would end | Book review

Tom Brokaw and James Reston Jr. separately recall their experiences during the scandal that brought down Richard Nixon.

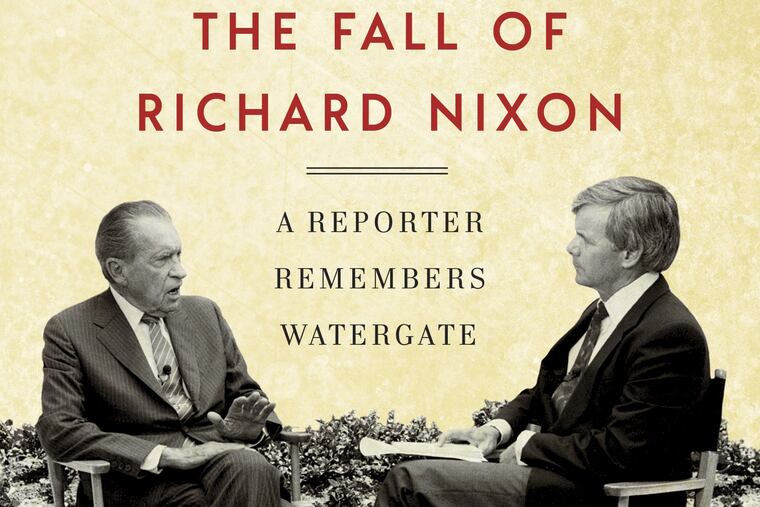

The Fall of Richard Nixon: A Reporter Remembers Watergate

By Tom Brokaw

Random House. 240 pp. $27

The Impeachment Diary: Eyewitness to the Removal of a President

By James Reston Jr.

Arcade. 168 pp. $19.99

Reviewed by David Greenberg

In March 1974, as Richard Nixon’s presidency was foundering, he spoke to the National Association of Broadcasters in Houston. The first question after his talk came from Dan Rather of CBS, who introduced himself (perhaps superfluously), to both cheers and boos from the largely conservative audience. “Are you running for something, Mr. Rather?” Nixon needled the correspondent. “No sir, Mr. President,” Rather replied. “Are you?” That tussle made news, but what tripped Nixon up was the follow-up from Rather’s NBC counterpart, Tom Brokaw, which the broadcaster recounts in his new book, The Fall of Richard Nixon: A Reporter Remembers Watergate. Because President Andrew Johnson had cooperated with Congress during his 1868 impeachment, Brokaw asked, wasn’t Nixon on shaky ground in claiming “executive privilege” as a reason to withhold material now? Brokaw had identified a key flaw in Nixon’s defense.

It’s impossible to read Brokaw’s account without thinking about the impeachment struggle underway between Congress and the Trump White House. What Brokaw tried to tell Nixon back in 1974 (and was ultimately affirmed that July by a unanimous Supreme Court in United States v. Nixon remains true today: “I knew from our research and from conversations with legal scholars, such as Alexander Bickel … that impeachment proceedings were exempt from claims of executive privilege.”

In timely fashion, Brokaw and his fellow journalist James Reston Jr. have published accounts of their experiences witnessing the Watergate endgame up close — the better, ostensibly, to help us interpret what’s happening now. Both are slight, breezy books with lots of brief chapters (sometimes just two pages), lots of pictures, lots of anecdotes, and little use for footnotes, bibliographies, or other scholarly apparatus that might deter the casual reader. Both provide a flavor of what it was like to live through those heady, fearful, historic days.

Though Reston’s The Impeachment Diary is a transcript of his actual diary (perhaps edited a bit) and Brokaw’s a nostalgic reminiscence, both books seek to convey the sights and sensations of Nixon’s final days. Brokaw, then 34 and a rising star in big-time network news, describes the mood of elite Washington, recalling the dinner parties of socialite Pamela Harriman to which he found himself invited: “Two tables of eight with finger bowls, rows of silver, excellent wines, and entrées served by the graceful house staff.” He meets Garry Trudeau, Carla Hills, Joe Biden, Ethel Kennedy, Pat Buchanan, Lee Marvin and many others. As a reader, you sometimes feel like the parent of a toddler chasing after him, given how many names he drops.

Reston, though just one year younger than Brokaw and not unaccomplished himself (he aided Democratic operative Frank Mankiewicz on his 1973 Watergate book, Perfectly Clear, and was teaching at the University of North Carolina), details more pedestrian surroundings: the “old-fashioned drugstore on East Capitol Street with a counter, great ice cream, and even egg creams for my Bronx-born wife. … Down the street a few doors is the legendary Trover’s Book Shop, perfect for browsing and for its stationery supplies in the basement.” Where Brokaw looks back confidently on his first appearance as a questioner on Meet the Press, Reston leaps with excitement when he learns that the Washington Post has accepted his op-ed piece about impeachment. He considers himself lucky when he scores one of the last seats in the press section for the high court’s announcement of United States v. Nixon.

Neither book purports to revise our understanding of who Nixon was or why Watergate happened. They don’t pretend to supplant such classics as Stanley Kutler’s The Wars of Watergate, Anthony Lukas’ Nightmare, or Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein’s The Final Days. As day-by-day accounts go, they cannot outdo the original Watergate ticktock, Elizabeth Drew’s Washington Journal, which was reissued a few years ago.

But each narrator is a companionable guide, and each book has juicy tidbits. Brokaw memorably relates the time White House Chief of Staff Bob Haldeman tried to hire him as White House press secretary. Reston, whom we typically see shuttling among the ongoing dramas on Capitol Hill, the Supreme Court, and the federal trial of Nixon apparatchik John Ehrlichman, is insightful in raising an issue that has become controversial again as the Democrats investigate President Trump: the problem of secrecy in the hearings. “Keeping their deliberations secret at first was wise,” Reston informs us about members of the Nixon-era House Judiciary Committee. “Secrecy sped up the inquiry, protected the rights of the accused, and educated the members at a deliberate pace beyond the glare of the television cameras.”

One thing both books capture well — Reston's in particular — is the fraught sense of not knowing how it would all turn out. It can be hard for a historian to convey to readers, who know the outcome of historical events, the unpredictability and disquiet that attended them in real time. Brokaw reminds us that even after the Supreme Court ruled against Nixon, "the pervasive uncertainty that had hovered over Washington for a year did not disappear entirely" — and the White House continued to speak and act as if Nixon would refuse to abdicate.

Reston also re-creates the feverish speculation about various possible scenarios. He tells of hearing one story, unverified, that Julie Nixon was urging her father, "Bring down everybody with you, Pa." Charles Wiggins — a California congressman who had loyally stood by the president until the White House was forced to release the tape that incontestably proved Nixon's role in the cover-up — assured Reston that "the protestations not to resign are an elaborate charade to show the world that someone is still president, while behind the scenes they work out the transition of power." Still, no one really knew what would happen until Nixon stepped into the helicopter departing the White House lawn.

David Greenberg is a professor of history and of journalism and media studies at Rutgers University and the author, most recently, of “Republic of Spin: An Inside History of the American Presidency.” He wrote this review for the Washington Post.