The dance world remembers Philadanco’s Debora Chase-Hicks, who also dazzled with Alvin Ailey

Choreographer Rennie Harris, who knew her as a friend and mentor, echoed many when he called Chase-Hicks, who died early this month, a pillar of Philadelphia's dance community.

Dance Theatre of Harlem’s resident choreographer, Robert Garland, clearly remembers his first time meeting Debora Chase-Hicks. “She was in Philadanco with my cousin, Deborah Manning, and they were doing 32 fouéttes to the disco song “Ring My Bell.” They were just having fun at dance rehearsal, but I was just amazed.”

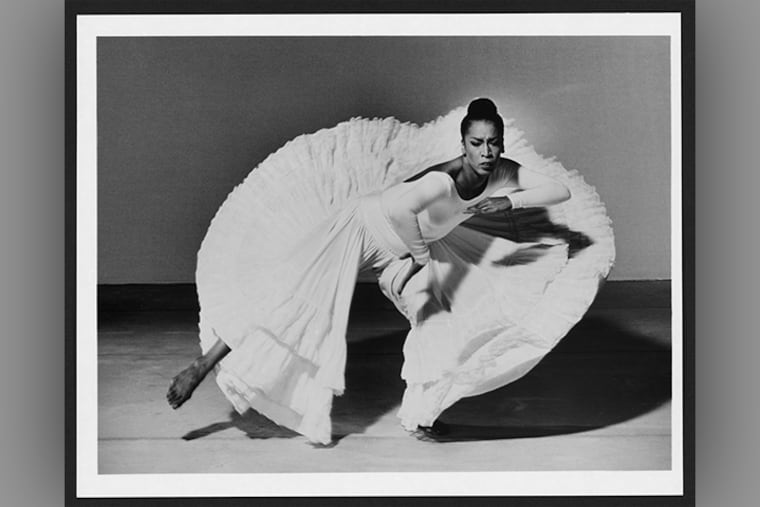

It’s a sentiment you hear — again and again — when distinguished names in dance remember Chase-Hicks, a pioneer with both Philadanco and Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater who died May 6 at age 63 after a brief illness. People saw her dance, and they were electrified by the possibilities of what dance could be.

Chase-Hicks “made me want to dance like her,” says Cheryl L. Burr, who also danced for both Philadanco and Alvin Ailey, and was a student at Ailey when Chase-Hicks was a dancer with the company. “She had the most beautiful arabesque, and technique to die for. When Chase danced, you felt the spirit, the ‘essence’ of whatever choreography she was in!”

Kim Bears-Bailey, a celebrated Philadanco dancer who is now the company’s artistic director, says that when she first joined the company and saw Chase-Hicks on stage, she said, “I want to do that, like her. I wanted to affect people the way she did.”

“She had a gift,” recalls Philadanco alumna Karen Pendergrass, who danced alongside Chase-Hicks in Philadelphia. “Debbie danced from her spirit. She had a gift. Lots of dancers go through the motions, but everything with Debbie, you always felt it.”

“We were on stage a lot together, so I felt her power,” says Raquelle Chavis, a fellow Ailey dancer who is now artistic director at Geechie Anne Productions in Asheville, N.C., “She could make you laugh one minute, make you cry the next. She could even make you feel frightened, like when we did Masekela Langage. It was wonderful to watch her transformation.”

Born in 1957, Chase-Hicks was a part of the generation of Black dancers, many trained in classical ballet as children, who were instrumental in bringing top-flight modern dance to international audiences. They underscored that Black choreographers and dancers had the talent and ability to tell stories, both particular to Black life and those that were universal.

She moved to Philadelphia from Denver as a child, and began training at age 10 with Philadanco founder Joan Myers Brown at the Philadelphia School of Dance Arts.

Brown says it was her privilege to watch Chase-Hicks metamorphose from student to dancer, joining the company as a teenager in 1974. And then, Brown says, “I watched her change from just a dancer into an artist when she did Autumn Wylde. … She was 18 and she had blossomed.”

Like Chase-Hicks, Garland joined the Philadanco company when he was a teenager, and he says it wasn’t just her stage presence that stood out. “She had a brilliant mind.”

Once, after choreographer Talley Beatty had abruptly departed, he says, Chase-Hicks made the wise decision to preserve his movements. “Her presence of mind turned out to have historic implications,” Garland says. “The ballet that they preserved became Philadanco’s first hit, Pretty is Skin Deep, Ugly is to the Bone, and it was a turning point for the company.”

Brown offered Chase-Hicks a position at Philadanco after she left Alvin Ailey in 1992. She remained with the Philly company, as coach and rehearsal director, for the rest of her life. “She maintained the level of excellence that I expected,” Brown says. ”I no longer had to rehearse or coach because I knew I had someone I could count on.”

Pioneering house and hip-hop dance choreographer Rennie Harris says he often rehearses with his company, Rennie Harris Puremovement-American Street Dance Theater, in the Philadanco building and came to know Chase-Hicks as a mentor and friend after she’d retired from the stage.

He and his dancers knew her “as a dance pillar in Philadelphia, a major part of Philadelphia history,” he says. “She was a force and everybody respected her, including street dancers. She was always looking out for us.”

Harris also admired Chase-Hicks’ enthusiastic, consistent promotion of Philadelphia. “A lot of people who become successful leave Philadelphia and don’t really push the banner for Philly. She was one of those who would fly the Philly flag.”

Harris called her passing “a sad day for Philadelphia.”

The loss was especially acute at Philadanco, where Bears-Baily expressed gratitude for having worked “beside my idol.”

“Sometimes you meet people who aren’t reachable. They aren’t attainable, because they’re so big. But she was attainable,” Bears-Bailey says. “She wanted to give the lessons, and receive the lessons.

“I know there are going to be some days when I turn to my left, because she always sat to my left, and I’m gonna say ‘Hey Chase,’ and I know she’s gonna be listening.”

Nadine Matthews is a freelancer writer based in New York who has written for Dance Magazine, Dance International, Shadow and Act, and many newspapers throughout the country about arts, culture, and society.