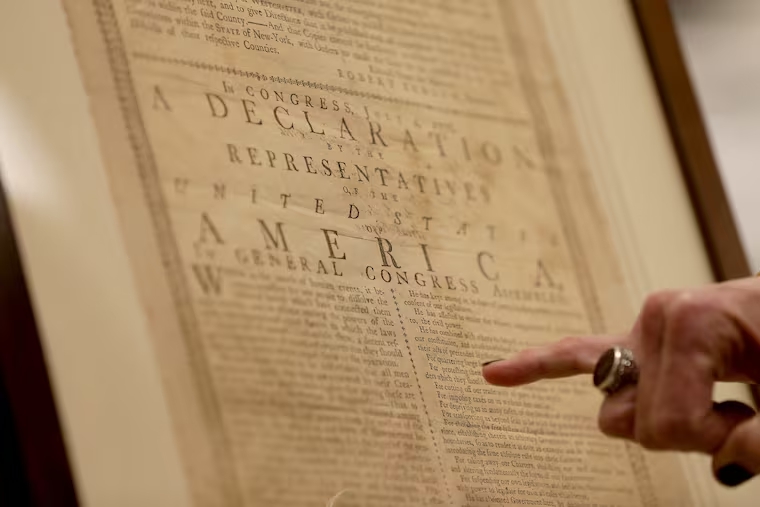

Museum of the American Revolution will show off a version of the Declaration of Independence that hasn’t been seen publicly for a century

On view from June 18th until the end of the year, the Museum of the American Revolution’s newest printing of the Declaration of Independence is unique in both condition and its historical timing.

For the first time in more than a century, one of the better preserved printings of the Declaration of Independence is on display and you can see it at the Museum of the American Revolution until the end of the year.

The nearly mint-condition printing is perfectly readable with only two barely noticeable blemishes on the linen-fiber paper. It also happens to be one of five known printings announcing the New York delegates support and adoption of the Declaration — a pivotal last step in the formation of a united front against the British king.

In the months leading up to the signing of the Declaration of Independence, thousands of these broadsides — unsigned printings that the recipient would often read aloud; think of it like 18th century breaking news — announcing freedom from British rule were printed and distributed across the colonies but few of these documents would survive 240 years among the elements: light damage, fires, flooding, human handling, and even burning ink. Most known surviving printings of the Declaration are fragile and degraded, displayed on a monthly rotation schedule by the few museums lucky enough to be able to. This printing is unique, even by the standards of its more popular National Archives counterpart, the famous and faded signed original that resides in Washington, D.C.

“When we have a chance to see an object like this that really was a witness, it’s incredible,” said Scott Stephenson, CEO of the Museum of the American Revolution. “The copy that is so famous at the National Archives — that stayed with Congress, so most people didn’t see that. That’s the power to me of looking at something like this. Real, regular people were looking at those exact words on that exact piece of paper, reading that we’re all created equal.”

The broadside on display was printed the same day George Washington read the Declaration of Independence to the Continental Army and a group of soldiers toppled the statue of King George III at Bowling Green, in Manhattan, and was among 500 made by New York publisher and printer John Holt. It’s addressed to Colonel David Mulford, an East Hampton regiment leader who received the document from his major, Uriah Rodgers. The major arrived on horseback with the news of New York’s support — a detail revealed by a handwritten note on the reverse side of the printing.

The Holt broadside printing remained within Mulford’s family for about 240 years following his death in 1778. It was last on display in the 1800s, hung by candlelight in the home of the colonel’s great-grandson. That was followed by 100 more years carefully preserved by generations of Mulford women, most recently within a dark, cool desk drawer wrapped, in part, in a towel.

The Declaration wouldn’t see the light of day again until a member of the Mulford family put it up for auction in 2016. Along with 82 documents chronicling the lives, oaths and property of the Mulford family, it sold for around $2 million total to Holly Metcalf Kinyon.

Kinyon, who was in Philadelphia on Monday, described the document as awe-inspiring during its private unveiling in the museum’s curatorial workroom. She isn’t a student of historical preservation or a collector. She didn’t even know the broadside existed until she read about the auction. She is, however, a descendant of John Witherspoon, one of the Declaration’s 56 signers. (Actress Reese Witherspoon has claimed she is among the New Jersey delegate’s other descendants.)

Now retired from the financial and public relations sectors, Kinyon says her decision to acquire and display the printing was as much a goodwill gesture to past and future Witherspoons as a way to preserve the public’s access for 200 more years. “I didn’t think the chance would come again in my lifetime to be able to connect our Witherspoon lineage with the Declaration,” she said.

While the signer’s descendant could have loaned it to any historical agency, she says the Museum of the American Revolution’s proximity to the Declaration’s official signing made it the perfect fit for display.

“When you get five feet away from where this Declaration will be displayed, there’s a wall titled ‘The Promise of Equality,'" said Stephenson. “It is such an important aspect of our interpretation — to remind people and ask that question, ‘Who does this apply to?’”