Remembering Angel Anderson, the artist behind Philly’s iconic ‘King of Jeans’ sign

The airbrush artist most famous for the kitschy Passyunk Avenue men's clothing store found a second calling restoring and painting religious artwork.

When developers replaced the iconic King of Jeans sign with condos in 2015, they asked the sign’s designer, Angel Anderson, if she would like to have it back.

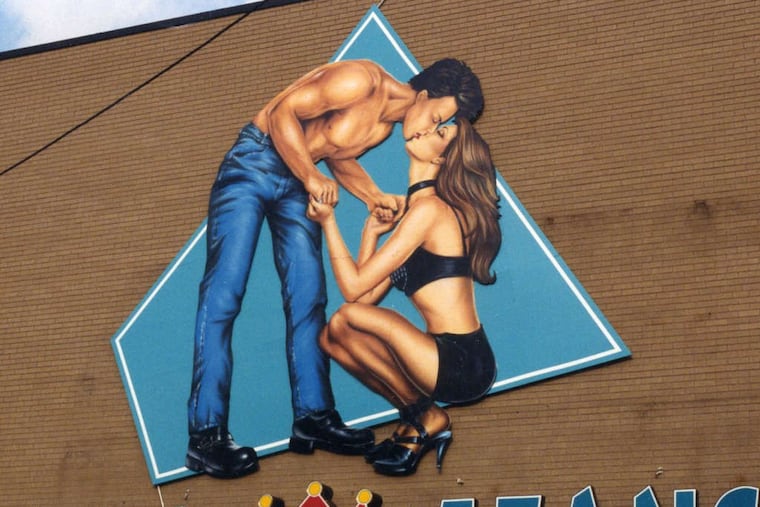

By then, the sign, which hung for two decades in all its garish, suggestive glory above Passyunk Avenue, had transformed into a celebrated piece of South Philly iconography. Anderson’s towering, shirtless jeans-wearing King and squatting Queen in hot pants and heels inspired album titles, short stories, and role-swapping T-shirts. Hailing it as a shrine to the avenue’s fading kitsch and unself-conscious weirdness, civic groups strove to keep it in the neighborhood. A museum dubbed it a “20th century landmark.”

Anderson, who designed the 16-foot-tall sign for a clothing shop across the street from her studio, had lived in the shadow of her famous sign long enough.

“It became iconic to everyone but her,” said Anderson’s brother, Joe Scorza.

Even before the sign came down, Anderson, who died in July at 58 after a long illness, had ascended into an entirely different realm of art — one that would take her far from the avenue and her sign. She painted soaring artwork for a mosaic installation in the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, the largest Catholic church building in North America.

She spent months restoring biblical murals and other artwork inside a crumbling 19th-century cathedral in the Caribbean. And she repaired irreplaceable religious statuary and art pieces, including a historic oil painting commissioned by St. John Neumann himself.

The artist who airbrushed stunningly lifelike portraits of Madonna, Scarface, and Kurt Cobain across a generation of South Philly T-shirts, jackets, and backpacks, and who was perhaps most famous for designing an almost-obscene men’s denim ad, had found her second calling — restoring the face of God.

‘A professor told her she would never make it’

“She was my sister, but I was in awe of her talent,” said Scorza, of Anderson, who was treated at a subacute care facility for nearly two and half years after suffering cardiac arrest in 2022.

The youngest daughter of a vending machine mechanic and a waitress, she grew up on Ritner Street and studied at the Art Institute before dropping out.

“Ironically, a professor told her she would never make it,” Scorza said.

Instead, she took a job airbrushing T-shirts in Wildwood. Soon, she opened her own studio on Passyunk Avenue. Her photo-like portraits of rock stars, pinup girls, and celebrities decorated the window. The shop quickly became a neighborhood staple.

“Growing up in South Philly in the 1990s, everyone had to have an Angel piece,” said Tony Trov, cofounder of the South Fellini T-shirt shop. “It was the hottest thing. You almost couldn’t get your hands on it. Her stuff was hyper real.”

Before long, her airbrush artistry was recognized nationally, with three of her works, including an early religious piece, a reproduction of Botticelli’s “The Madonna of the Magnificat,” published in a 1994 airbrush anthology. Soon, her designs dotted neighborhood businesses, like Lorenzo & Sons Pizza on South Street.

“It was amazing how she could work the details with that airbrush,” said Steve Calabrese, owner of Uneeda Sign, who often worked with Anderson. “She could get that airbrush and pull an eyelash. She could paint something so fine.”

Then, the King of Jeans called.

‘It spoke to the moment’

It was just another commission.

Anderson and Calabrese did it together. She worked over the design of the lip-locked couple, while Calabrese built out and partially painted the sign.

Later, Anderson would sit in Calabrese’s studio and laugh over the iconic status of the sign, an homage to the popular Patrick Nagel-inspired style of the 1980s.

“We’d say, ‘What’s the fascination?’” he said.

Some saw it as art. Some saw it as kitsch. Many saw it as a depiction of the prelude to oral sex. More simply, it caused anybody who ever saw it to look up and say, “Oh, my god.”

It became part of East Passyunk.

“It spoke to the moment in the neighborhood,” said David Goldfarb, of the Passyunk Square Civic Association, who tried finding the sign a new home in the neighborhood in 2015. A possible deal with a South Philly business who wanted to display the sign at the time was scuttled by a neighboring business, he said. It’s now stored at a Northern Liberties salvage company under the agreement it not be sold.

“Some people loved it, some didn’t,” Goldfarb said. “I don’t think you could ask for much more in a piece of commercial signage. I love it and miss it.”

After all those years, Anderson was just tired of looking at it.

Anderson’s legacy

“Angel’s talent was like that of a highly trained classical artist,” said Louis DiCocco, president and director of the St. Jude Liturgical Arts Studio, which restores church artwork. “She may not have considered herself that, but she was right up there.”

DiCocco initially hired Anderson around 2005 for her airbrushing skills, a common medium for art restoration, he said. But she quickly moved from murals to hand-painting, gold-leafing, modeling, and statue work. Anderson seemed to bring the religious artifacts to life, DiCocco said.

“She was able to convey such a sense of depth and shadowing detail that she really made the statues almost seem to talk,” he said

Her Passyunk Avenue studio became filled with sacred artwork, her family said.

“She’d text me, and say, ‘Look, here’s Jesus’ new hand,” said Anderson’s sister, Marie Silvestro, with a laugh. “She loved that work.”

Anderson thrilled in the details and challenge of the restorations, taking a class in oil painting before delicately repairing a fragile portrait of St. Anthony that now hangs in St. Peter the Apostle, the church located above the National Shrine of St. John Neumann. She climbed on rickety scaffolding to hand paint artwork inside a nearly 200-year-old cathedral in the U.S. Virgin Islands.

Around 2015, in by far her most prestigious job, she painted the original art used for the final mosaic installation in the striking Trinity Dome of the Basilica of the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington. Her artwork completed the ornamentation of the Shrine’s great upper church, a project that began in 1959.

For months, she sketched and painted images of the four evangelists in her fine art studio, Bach playing on the radio, her cat stalking her feet, and her door open to South 13th Street, and the nearby avenue, where her famous sign once hung.

“That is her legacy,” DiCocco said of the mosaic installation. “The Basilica is one of the most beautiful churches in the world. To be able to say that you’ve done artwork there is quite a feather.”

In the days after her sister’s death, friends flooded the family with photos of T-shirts and sweaters that Anderson had long ago airbrushed, but that they had never worn or washed, said Marie Silvestro.

“They didn’t want to ruin it,” she said.

And when she lay dying, her friends and family hung images of her work around her bedside, everything from pinup portraits from the King of Jeans days to her grand religious works, so she could be surrounded by all the beautiful things she created.