A Penn professor designed lab-grown ‘human steaks’ as satire

"Ouroboros Steak," which Orkan Telhan helped create for an exhibit last year at the Philadelphia Museum of Art, is now the subject of global debate.

Orkan Telhan, associate professor of fine arts at Penn’s Weitzman School of Design, is not actually promoting cannibalism.

But then again, neither was Jonathan Swift, author of A Modest Proposal, which suggested the cooking of babies would alleviate problems of both hunger and poverty in 18th century Ireland.

Nevertheless, a diminutive art installation that Telhan created for an exhibit last year at the Philadelphia Museum of Art is being interpreted that way in a global debate that echoes some of the caustic moments from the late ’80s and early ’90s culture wars.

“So real life Soylent Green,” wrote one Fox News website reader who comments as BobPies.

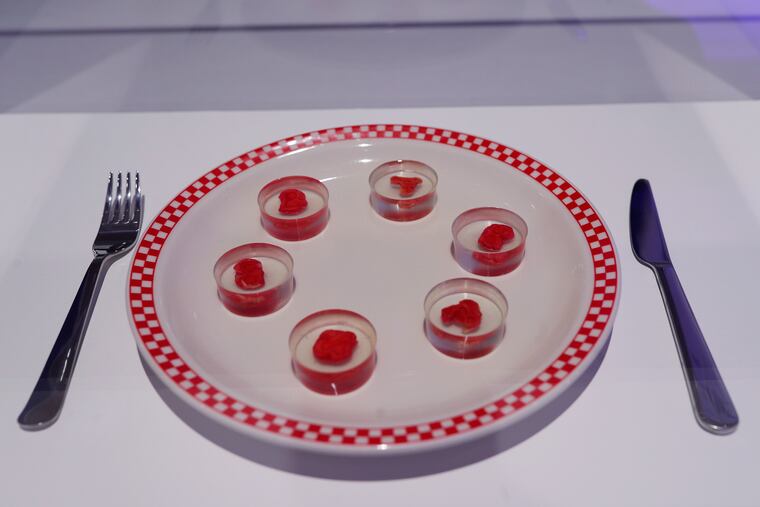

Telhan’s work, dubbed Ouroboros Steak, was commissioned by the Art Museum and created in collaboration with Andrew Pelling and Grace Knight. It appeared at the museum in 2019-20 as part of a sprawling exhibition, “Designs for Different Futures.” Ouroboros consists of an elegant dinner setting with small pieces of meat-protein grown from human cells.

The bright red silver-dollar-size steaks are arrayed on a plate and silverware rests nearby, ready for use in an elegant dining experience.

Ouroboros Steak was created from human cells harvested from the mouth, via cotton swab, and expired blood about to be discarded by a blood bank. It sparked no controversy during its appearance in Philadelphia. But now the exhibition is at London’s Design Museum and is up for a big award. Fox News published a piece on its website late last month, “Grow-your-own human steaks meal kit is not ‘technically’ cannibalism, makers say,” and the internet has been howling ever since.

“What happens when humans develop a taste for this and want to expand to different cuts i.e. Shoulder roast, Leg of Sam … Baby Baby back ribs Boneless Tender Groin,“ BobPies said in his comment on the Fox News article. “Who knows?”

And it was off to the races.

“Thinking of eating steaks made from human cells is repulsive,” said another Fox commenter. “Sounds like a prelude to an apocalyptic future dystopia where democrats, (you know those people that say bad is good and good is bad) would rule and convince the populace that deviant behavior is the norm …”

From Fox News, commentary spread to Reddit message boards and Twitter, where much of the conversation has been more reflective:

Sofia Carpio, @Sofl77, wrote: “This triggered so many feelings inside of me (disgust, worry for the future of cultivated meat, of #climatechange, attempts to reason out this reaction) that I think it is a great piece of art.”

Stories have sprouted across the internet — from The Spoon’s “Human Steak: the Next Lab-Grown Meat?” to Science Times’ “Is This Lab-Made Ouroboros Steak Ethical To Eat? Experts Say Yes.” The New York Times first reported on the controversy.

Food-tech as satire

Clearly a serious work of satire, Ouroboros (named after the mythical snake eating its own tail) contains a DIY meal kit, and the whole is presented in promotional language. Ouroboros Steak also has its own website.

“Growing yourself ensures that you and your loved ones always know the origin of your food, how it has been raised and that its cells were acquired ethically and consensually,” the website states. (The kit is not for sale, and it is unknown if anyone has eaten the meat.)

Telhan says the piece is a “critique of the current food technologies, especially the lab-grown meat industry, which promises a lot of hope about the future of making meat or protein sources without killing any animals.”

But, he says, there is considerable animal exploitation in such production, despite the claims otherwise.

“We just wanted to provoke the conversation a little bit by saying that actually growing human cells from waste, human blood, is actually more sustainable” than current lab-grown meat production.

“That’s obviously triggered the controversy because it’s such a taboo concept to think about humans being consumed by themselves,” he said. For Telhan, Ouroboros is “a critique of human behavior as opposed to saying that here’s another solution for your protein sources.”

At the center of the storm

The breadth of media commentary is a surprise, Telhan said, but understandable given the political climate and the story play on Fox. And it’s not all necessarily negative.

“I think that it’s desirable,” he said. “And I always see these comments as feedback. Obviously some of them cross the line and they really are very offensive. But that is part of the game. Design holds a mirror to the society. This piece basically holds a mirror to the current climate, and [people] needed to talk about these issues, and this just created a new context where people attack each other.

“But obviously from our perspective, a lot of people think that design always serves consumers and design always has to find solutions to problems. But design is always also a very critical tool, much like art.”

Michelle Millar Fisher, who was assistant curator for European decorative arts at the PMA and was instrumental in commissioning Telhan’s work for the exhibition, says Ouroboros asks viewers to think about where food comes from, how it is processed, and what ethical questions the process raises. Few people, she says, ever confront the violence of meat production. Similarly, few ponder environmental degradation resulting from growth of plant-based food.

Telhan, she says, takes “the notion of taking protein from a source that is the human body” and considers “the many different issues from the taboo and the ethics, to the ways in which we might present it for consumption.”

Fisher is now curator of contemporary decorative arts at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

“It is a speculative project,” she says. “But it’s based very much on science that exists and the need for us to think more sustainably about how we come by our food sources. It’s not meant to be an empty provocation. It’s meant to very seriously offer an alternative, in many ways. As a curator I wasn’t interested in bringing it into the museum because it was flippant or funny or in any way unserious.”

That said, “I don’t mean, by unserious, that it doesn’t have humor, I mean, the wonderful thing about it is that they thought about this project so completely. They have a social media account for it, they have, you know, copy for it that reads like the type of copy you might get on a Blue Apron or another kind of meal service program. So they thought about it wholly.”