A Native American adolescent’s skull at the Penn Museum moves closer home

The Museum has established the deceased's tribal heritage and is proceeding with the steps toward repatriating the remains.

The skull of an Indigenous adolescent from a Maine tribe that became part of the infamous cranial collection at the Penn Museum has moved a step to being restored to their people.

The remains of the person of unknown gender could be turned over to representatives of the Wabanaki confederation as soon as April 18, according to a recent notice published in the Federal Register. The notice, filed Wednesday, said the Penn Museum has determined that the remains have a cultural affiliation that its experts believe meet the criteria for repatriation under the Native American Grave Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA).

The notice sheds some light on the journey of the child’s remains.

According to Penn’s research, the skull belonged to an adolescent between 12 and 15 years old. Sometime before 1840, a doctor named Paul Swift obtained the remains under unknown circumstances, probably in Maine. Swift practiced medicine in Nantucket but moved to Philadelphia in 1841.

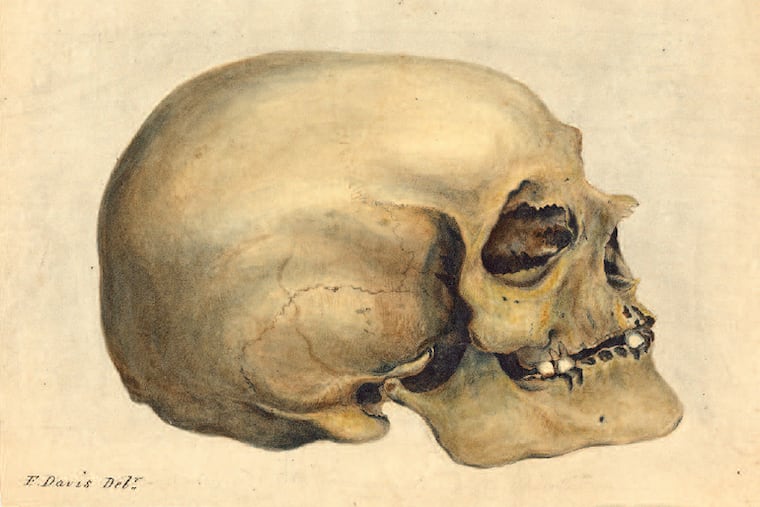

The notice states that in 1840, the remains “were transferred” to Samuel G. Morton, a white supremacist scientist. The skull was stored in Morton’s now-infamous collection. Morton died in 1851, after which the Academy of Natural Sciences bought his collection in 1853. In 1966, the collection was loaned to the Penn Museum and formally gifted to the museum in 1997. In 2020, Penn formed the Morton Collection Committee to look into issues such as repatriation.

Morton amassed a collection of over 1,300 craniums, including remains of Black Americans and Indigenous Americans, which he intended to use to advance his racist views. Some remains have been known to be obtained through nefarious means including grave digging from around the world.

Science.org reports that in 1840, José Rodriguez Cisneros, a Cuban doctor, dug up the graves of enslaved Black West Africans who worked in a plantation outside of Havana. He removed their heads and shipped their skulls to Morton in Philadelphia.

As Penn doctoral scholar Paul Wolff Mitchell writes in his 2021 paper, “Black Philadelphians in the Samuel George Morton Cranial Collection,” Morton would also steal skulls from “unmarked communal burial ground of the Philadelphia almshouse, a free public hospital at which many Penn Medicine faculty worked and trained medical students.”

On several occasions, Penn has come under strong criticism for its handling of the human remains in its custody, including the Morton skulls. A burial service Penn held last year for 19 skulls of Black Philadelphians from the Morton collection was condemned by critics who said sufficient efforts to identify the remains, and possibly find kin, were not undertaken.

In this past week’s Federal Record notice, it’s stated that, based on museum records, other sources, and after consultation with the Maine Wabanaki Intertribal Repatriation Committee, it had been determined the human remains of the adolescent are “culturally affiliated” with all four tribes represented by the Wabanaki committee.

“Based on the wishes of the Tribes, the Penn Museum supports the disposition of the human remains described in this notice to be made to the Houlton Band of Maliseet Indians, Mi’kmaq Nation, Passamaquoddy Tribe (Indian Township and Pleasant Point) and Penobscot Nation, as represented by the Maine Wabanaki Intertribal Repatriation Committee,” the notice reads.

Other steps in the process specified by the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act (NAGPRA) need to be followed. One of those processes involve making sure no tribe outside of the Wabanaki confederation claims ancestry with the deceased adolescent. The notice calls for a formal request for repatriation, and states that it can occur on or after April 18.

Since NAGPRA became law in 1990, the Penn Museum has sent over 4,500 letters to federally recognized tribes about their holdings, according to a Penn statement. As of 2024, 70 formal repatriation claims had been received and 50 repatriations under NAGPRA were completed, it said.

The results of those repatriations were the transfer of 334 sets of human remains, 830 associated funerary objects, 98 other funerary objects, 24 objects of cultural patrimony, eight sacred objects, and six objects claimed as both cultural patrimony and sacred, according to the statement. In addition to those, 21 sets of human remains had completed the NAGPRA process and were awaiting return to their affiliated tribes.

“In our 35-year history of working with NAGPRA, centering human dignity and the wishes of descendant communities govern the treatment of human remains in our care,” a Penn Museum spokesperson said.

The article has been updated with details on how Morton procured skulls for his collection.