Penn library will return 9th-century documents found to have been stolen from Italian archive

The university received the documents in 2011 as part of a large gift of books and manuscripts from collector Lawrence Schoenberg, who had purchased them from a venerable London bookseller.

The University of Pennsylvania has voluntarily agreed to return two ancient parchment documents to an Italian archive from which they had been stolen, apparently in the 1990s, according to a formal stipulation filed in federal court in Philadelphia last month.

The heist was the work of an unknown thief and happened years before the papers surfaced at Penn.

The documents, which record land transactions in the 820s in southern Italy, were acquired in the late 1990s by the late collector Lawrence J. Schoenberg, who bestowed his collection of manuscripts and books on the university in 2011.

The Schoenberg Collection at the University of Pennsylvania Libraries, consisting of about 300 separate items, is particularly rich in medieval and Renaissance books and manuscripts.

According to the filing in federal court, which Penn signed off on in mid-November, the two documents were stolen from the archives of La Trinità della Cava, a Benedictine abbey near Salerno widely known as the Badia di Cava.

It is not known what the monetary value of the documents might be, but their antiquity makes them unusual.

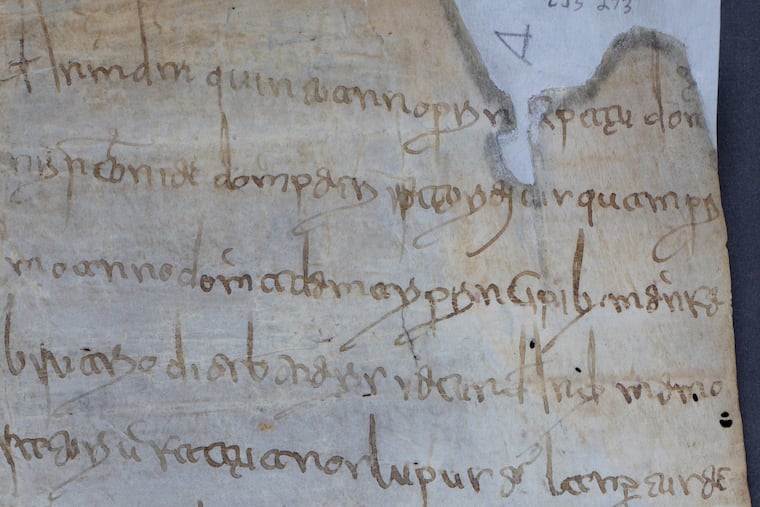

The first, known as the Waldipertus Land Grant Document, was recorded in 821 in Benevento, Italy. It details “a grant of level land in Murtula by Waldipertus (Gualdipertus), son of Aldelpertus, to Lupus, Lampertus, Amipertus, and Walpertus (Gualpertus), sons of Bonepertus, Dadeprandus, son of Radulus, and Adelprandus, son of Ragimpertus,” according to the court document.

The second document, known as the Martinus Land Sale Document, was recorded in Benevento in 823 and describes the sale of land “including a vineyard and orchards in A lo Tuoro, by Martinus, son of Forte, and his son, Maius, to Bonepaertus, son of Alfanus, for 4 Beneventan gold soldi and 2 tremisses."

Both ninth-century documents are written in Latin on parchment and measure about 17 inches in length and six inches in width.

Penn officials said they had little information about the history of the documents.

University spokesman Ron Ozio, emphasizing the university’s innocence in the matter, gave the following account in an email:

“In late 2017, a French scholar recognized these documents as having come from the collection of the Badia di Cava archives. The archives enlisted the help of Italian officials, who in turn requested assistance from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security to repatriate the documents to Italy. The U.S. Attorney’s Office contacted the [Penn] Library in May 2018 and provided documentation.”

Ozio said the university met with the U.S. Attorney’s Office and two investigators from the Department of Homeland Security to review the documentary history.

“The library quickly concluded that the documents had come from the Badia di Cava archives and should be returned,” Ozio reported. “The university received the documents innocently, acted promptly when presented with the facts, and signed the [federal court] stipulation and order.”

According to the court filings, the documents, which remain at Penn for the moment, were reported missing from Badia di Cava in 1996. They were photographed in the archives at some point not long before 1996, but when they might have been stolen remains unknown.

In 1998, Schoenberg, who died in 2014, paid a visit to Maggs Bros., a venerable London bookseller, where he bought both documents. A representative of Maggs said the bookseller, in business for about 170 years, knew nothing of the theft, which he described as distressing.

Maggs said it planned to contact the university but had no further comment at the moment.

The university website for the Schoenberg Collection indicates no known provenance for the documents prior to Maggs.

Local authorities on old books, who spoke anonymously because they did not want to be seen as commenting on the Penn situation, said it would be virtually impossible to completely double-check the provenance — the ownership trail — of every acquisition coming into a large collection. The Penn Rare Book and Manuscript collection numbers more than 400,000 rare books and about 15,000 linear feet of manuscripts.

“The important thing is that Penn did the right thing — they returned the documents,” said one observer.

Ozio noted that “Penn Libraries is deeply invested in provenance research; indeed, it is the home of the Schoenberg Database of Manuscripts, the largest database in the world on the provenance of medieval manuscripts. We are also dedicated to making our manuscripts available to the world through high-quality digital images. In fact, the two documents in question were only identified by Italian scholars/authorities thanks to the fact that both were fully described and digitized on the Penn Libraries website.”