Eighty years ago, the Philadelphia Orchestra cut some superhit records. No one knew that until recently.

America was emerging from the Great Depression, German musicians fleeing Hitler were raising musical standards, and Philadelphia Orchestra musicians were recording anonymous albums

Long at the forefront of recording technology, the Philadelphia Orchestra once landed in a less-exalted but hugely successful marketing endeavor — possibly unprecedented — that is only now being explained, heard, and appreciated 80 years after the fact.

Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms were the selling points in a series of budget-label recordings — 1938-1940 — marketed and distributed through a publishing arm of the New York Post. Performers such as the Philadelphia Orchestra were nowhere to be listed, but now they are. A double-disc set titled Ormandy and The Philadelphia Orchestra, The Early Years ∙ Volume 5 is being released on Pristine Classical, a France-based label that specializes in refurbishing pre-1960s recordings. It’s the latest in the series of long-out-of-circulation Ormandy recordings, and is available to order through mail or digital download on pristineclassical.com/products/pasc726 for about $20.

Titled “World’s Greatest Music,” this series eventually stretched into 38 discs (78 rpm), and was based on the idea that an aspirational brand plus low overhead costs could appeal to a wide public that had only heard the name Toscanini. And it worked.

By 1940, the series had reportedly sold more than 1 million discs. Why the performing orchestras were kept anonymous hasn’t been fully explained. Perhaps to keep these recordings from undercutting other Philadelphia Orchestra titles on the market? Later, Reader’s Digest took up the idea with a series of now-acclaimed, British-made records with all artists receiving credit. In our time, BBC Music Magazine came with a free recording from the BBC vaults.

With the long-forgotten “World’s Greatest Music” series now being rediscovered, the identities of the performers have been revealed over the decades in dribs and drabs. Opera excerpts had major stars such as Rose Bampton — along with other now-iconic names such as conductors Fritz Reiner and William Steinberg and orchestras including the New York Philharmonic and NBC Symphony. Together, the recordings were an underground documentation of East Coast classical music activities when America was emerging from the Great Depression, great German musicians fleeing Hitler were raising musical standards in the U.S., and Walt Disney was animating The Rite of Spring in the film Fantasia.

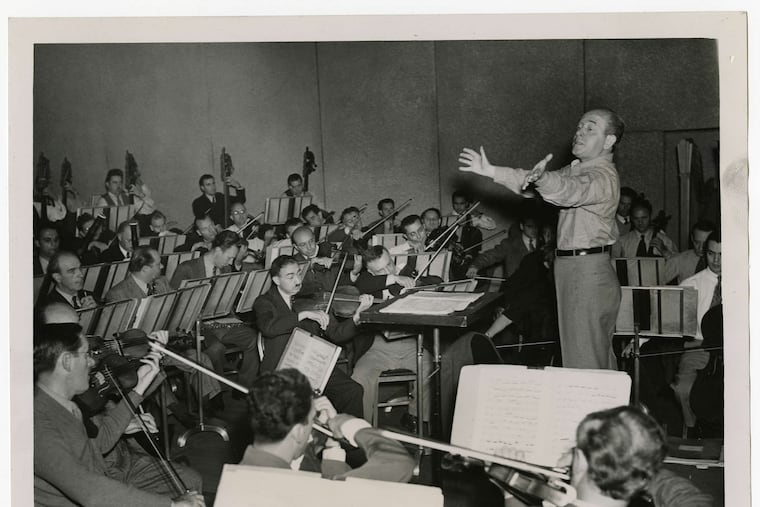

Amid all of this, the Philadelphia Orchestra was working at peak efficiency under its then-new leader Eugene Ormandy.

“Since the works were all standard repertoire, it was assumed that the musicians knew them well; and to keep costs down, little if any rehearsal was probably done at the sessions,” said Mark Obert-Thorn, a sound restoration expert, former Philadelphian, and producer for Pristine Classical, who has spearheaded the discovery of old Ormandy recordings. “Only a handful of sides required more than one take; but then, that was not unusual for Ormandy and the Philadelphians.”

According to the recording logs researched by sound archivist Michael H. Gray, the Nov. 11, 1938, session had the orchestra knocking out Bach’s Brandenburg Concerto Nos. 2 and 3, plus Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 in a mere three hours. Though the size of the orchestra was cut down to save money — 74 players for Brahms’ Symphony No. 2, about two-thirds of the usual contingent — the musicians did include two names who leave longtime orchestra followers misty eyed: flutist William Kincaid and oboist Marcel Tabuteau.

No wonder the Bach performances hold up so well, though Kincaid and Tabuteau aren’t the only reasons.

The lumbering tempos and clueless phrasing characteristic of Bach performances in this period aren’t heard here. The Brandenburg Concerto No. 2, in a highly comprehending reading that also captures a version of the Philadelphia sound, remains beguiling 80-plus years later. The Mozart symphony and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 are both good middle-of-the-road performances that catch fire in the spirit of live performances — not surprising given the lack of retakes.

In the Schubert Symphony No. 8 ( “Unfinished”) and Brahms’ Symphony No. 2 one particularly feels the influence of Leopold Stokowski, the main architect of the lush Philadelphia sound, but also a proponent of free bowing among the strings that gave the sound a distinctive shimmer. And that’s still there. Especially in the Brahms, one hears graceful portamento, a manner of phrasing that connects the notes into a longer melodic line — a practice that died out after World War II.

One wonders why such distinguished musicians would be involved in such a “down-market” situation. Many reasons. The “World’s Greatest Music” line was produced by RCA Victor, then the orchestra’s home label. Maybe some corporate pressure there? Ormandy himself wasn’t yet a drawing card. He was still coming out of the shadow of Stokowski, who was still visiting the orchestra, shaking hands with Mickey Mouse in Fantasia, and off romancing Greta Garbo.

Also, a full-time Philadelphia Orchestra position was not then what it is now. For many classical musicians, freelancing in New York was more lucrative. And these “World’s Greatest Music” sessions — no doubt less expensive to run in Philadelphia’s Academy of Music than New York — were quick money for the musicians, especially when they didn’t have to schlep to the RCA studios across the river in Camden.

But there’s never a sense that the orchestra was on autopilot. Though perhaps humble in origin, these recordings — heard in a newly restored sound that is far better than one could hope for from this era — are a significant chapter in the orchestra’s history, as well as a thoroughly enjoyable one.