‘You can’t forget that it’s still hell inside,’ say the authors of a new visual book on mass incarceration

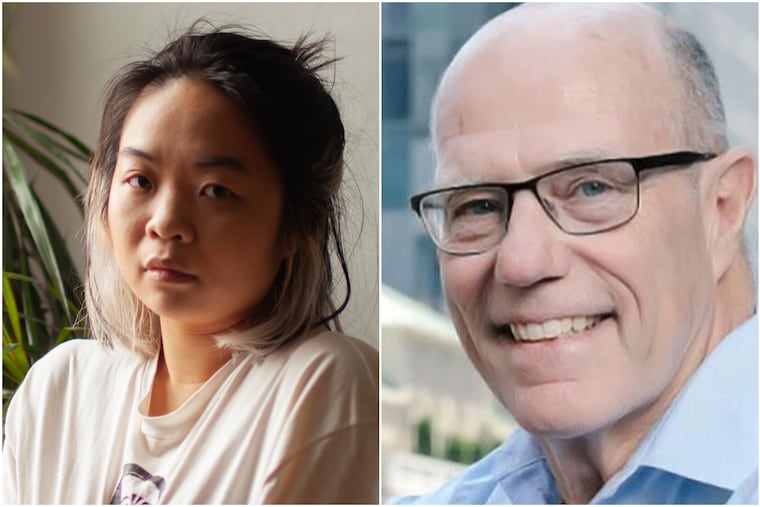

A Q&A with James Kilgore and Vic Liu, who are coming to Philly to discuss their book, “The Warehouse: A Visual Primer on Mass Incarceration,” on July 23.

Numbers can’t always capture the full story, especially with a subject holding as much deeply rooted history, conflict, and emotion as mass incarceration.

That’s why in May, formerly incarcerated activist and author James Kilgore and information artist and author Vic Liu published a book together on the subject, rich with art, graphics, and other pieces of visual storytelling. The Warehouse: A Visual Primer on Mass Incarceration gives an overview of how mass incarceration came to be, its scale, and what the experience is like for the people affected by it. The book features artwork not just by Liu, but also pieces commissioned from currently incarcerated artists.

While Kilgore and Liu’s book has a national focus, it also has a home at the Philadelphia Free Library for the next several months. At the Parkway Central branch, at 1901 Vine St., nine posters of Liu’s artwork from the book will hang until October.

Liu and Kilgore will visit the Free Library on July 23 at 6 p.m. for a discussion of their book.

Kilgore and Liu spoke with The Inquirer about The Warehouse, how they balanced showing the intimacy and the scale of mass incarceration, and why reform and abolition of prisons both have a place in solving the problem.

This conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

James, you already wrote a guide to mass incarceration in 2015. Why did you two believe that this topic needed to be updated and explained with a new visual emphasis?

Vic Liu: A lot of the written text on the carceral system tends to be slightly more academic, spanning from Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s Golden Gulags to Michelle Alexander’s The New Jim Crow. And a lot of them have an argument and it’s not so much — here, welcome to the horrible hell that is mass incarceration and how it came about.

So when I read James’ book, I immediately wanted to make it visual. Visuals and art and design provide so many more dimensions for you to access and communicate information. Text is so limited in its ability to talk about nonlinear narratives and complexity and emotion and it requires a high level of literacy that I don’t think matches what is available to most Americans right now.

“I wanted to make it out of materials that were available to create art in prison.”

James Kilgore: I was a fugitive for 27 years and spent a lot of that time in Southern Africa as an educator doing popular education for trade unions and community organizations. I wrote booklets on things like the World Trade Organization, free trade, etc. And when I got to prison in the U.S., I had the idea of applying that model for people who are incarcerated.

I realized that I really couldn’t share them with more than a handful of people, and sometimes nobody else in the prison, because they were just too difficult for people to read. The ideas were accessible, but the format was not. And then I felt like the work that [Vic] was doing and her ability to understand mass incarceration and the visual approach to it was rich enough to warrant putting this together.

This book and its artwork are intimate, while also providing plenty of data and academic framework. How did you achieve both of those ends, and how did you decide on which things to illustrate?

JK: The thing that was important and was challenging was to be able to strike a balance between giving a macro picture of mass incarceration, and giving also a flavor of the experience that individuals go through — whether they’re Black, whether they’re in men’s prisons, women’s prisons, LGBTQIA plus, immigrants, etc.

VL: I wanted it to feel like it belonged within the world of prisons. So I wanted to make it out of materials that were available to create art in prison. All of the paintings are hand painted, the cover is hand illustrated. There’s a visualization of the number of incarcerated people [in the U.S.], each silhouette is done by hand.

I think there is an ability to really just sit with the massiveness of the issue when you go through the trouble of doing it. I think there’s a lot of love in labor. That was important for me as a way to almost hold vigil over the issue.

JK: One of the things that gets missed in a lot of overviews of mass incarceration is what I call resistance. And that is the things that people do on a day-to-day basis to either recapture their humanity or improve their quality of life.

If you’re making prison wine, to me, that’s a form of resistance. If you’re using stuff that you find inside the prison to make makeup or eyeliner, that’s all about resistance. But I didn’t also want to just do a book that’s a collection of stories about the pretty pictures that people paint or the handbags that they make out of potato chip bags. But rather, to connect those things together.

VL: How do you depict the extent of dehumanization that the system imposes on people, and how do you balance that with platforming and highlighting the humanity of the people inside? Because there’s this tension there because when you highlight their humanity too much, you can’t forget that it’s still hell inside, right?

You end the book discussing the two main pathways for solving this problem, reform and abolition, by presenting them as equally valid. But often, people feel strongly about being in one camp or the other. Why structure it this way?

VL: There’s been a rise in purity culture, especially in the left lately. And I think that’s all well and good, except when you actually do need to help the very real lives and real individuals that are affected by the system. And we’re not going to get there if we’re all just trying to censor and break down and proofread everyone’s Instagram posts.

“I support abolition, but I want people to engage other points of view and figure out where they fit in.”

JK: I support abolition, but I want people to engage other points of view and figure out where they fit in, where abolition fits in. In some cases, you might be campaigning to have a prison closed, but in another situation where you don’t have the political power to do that, you might be fighting to get cheaper phone calls.

If all you ever read about prisons is abolition, you don’t understand prisons because you’re only looking at it through one lens. The minute somebody calls you on a flaw in your argument, you’re not able to respond because you haven’t really thought it through.

It’s not a set of dogmas to memorize. It’s a set of understandings to engage with.