How thieves took $5,620 from my bank account with old-fashioned check washing

Check washing is the latest old-school crime to make an unexpected resurgence, partly due to digital anti-fraud technology. Blocked from committing fraud online, thieves are using old techniques.

“Jordan Critchlow,” the Feds are looking for you. And for you, “Karen Woodson.”

Are those even your names? They’re what you called yourselves when you fooled my bank and grabbed my money — $5,620.

Fraud scholars tell me the dark art used against me is called “check washing,” the latest old-school crime to make an unexpected resurgence, like carjacking or in-person identity theft, at least partly because of modern, digital anti-fraud technology.

It took a month to get that cash back from our duped bank, WSFS. It would have been a tough month if, like so many Americans, we were living paycheck to paycheck, in these times of high inflation.

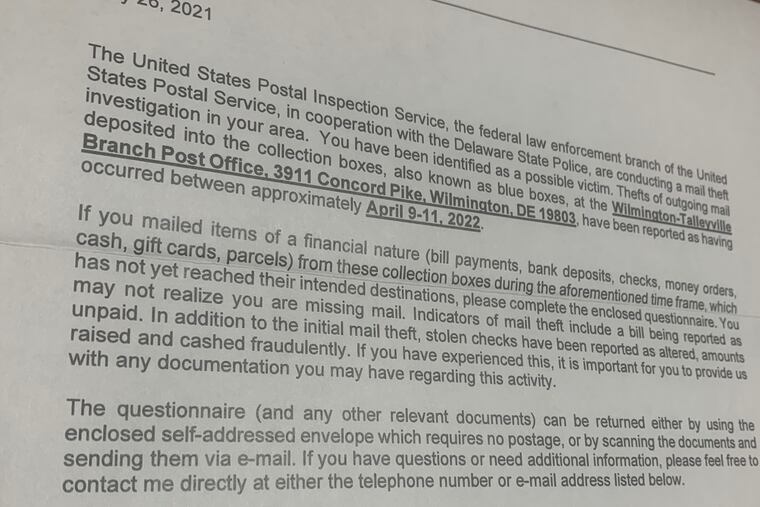

Federal agents suspect our monthly Delmarva Power check may have been among the items stolen right out of the blue mailboxes at the Talleyville, Del., post office, which faces busy U.S. Route 202. “You have been identified as a possible victim,” the head of a multifunctional team of Philadelphia-based postal inspectors wrote me in a letter that arrived June 13, detailing the brazen burglary.

» READ MORE: Checks are being stolen from Postal Service mailboxes, raising concerns about the blue boxes’ security

When protections are high-tech, criminals go old school

According to the U.S. Postal Inspection Service and industry groups, this sort of old-fashioned check fraud is becoming more common — a fact investigators blame, ironically, on digital anti-fraud technology — which is also a cause of our current epidemic of carjacking.

Does that sound backward? To be sure, the high-tech security adopted by big payment systems can disrupt thieves by making money harder to steal.

But it doesn’t reform the thieves — just pushes them to new methods. Or in this case, to precomputer ways of stealing — since the post office hasn’t made it harder to steal from mailboxes.

For example: “If key fobs [with security computer chips] make jacking a car more difficult, how you steal key fobs is, you stick a gun in someone’s face,” Postal Inspector George P. Clark said.

The same applies to bank check fraud. If chip cards make it harder to read account numbers from stolen credit cards, thieves will return to more primitive tactics of “stealing a check out of the mail-stream,” Clark added. Philadelphians reported a rash of check burglaries from post office boxes last winter.

I’m pleased to say “Jordan” and “Karen” didn’t do worse damage thanks to my vigilant wife, who has worked too hard as a long-ago banker, lately a preschool teacher, and careful mother of our six kids, to trust the banking system without checking our transactions every day. She spotted the phony withdrawals on May 12.

We called WSFS and had it close the account and open a new one. (For the second time in a year: Alert branch workers last fall caught a Pennsylvania man pretending to be me in a Chester County WSFS branch. Detained by East Whiteland police, he jumped bail, and has since been rearrested on criminal attempted ID theft and forgery charges.)

How did these latest thieves pull it off? They had a copy of my check, with the right account number.

They cribbed out my name and address and stuck on other personal information — called “check washing,” for the way thieves sometimes use a careful selection of ink solvents to blot off inconvenient data.

It’s an old technology, described in detail in convicted ID thief Frank Abagnale’s popular 1980 book, Catch Me If You Can, and turned into an amusing Leonardo DiCaprio movie in 2002.

Consumers last year reported $2.3 billion in impostor scams — people pretending to be them. That loss was nearly double the $1.2 billion lost a year earlier, according to the Federal Trade Commission. Overall consumer fraud losses rose 70% in 2021, to $5.8 billion. The typical check scam cost consumers nearly $2,000, more than other common scams. People in their 20s are more than twice as likely as other Americans to get hit.

Bank fraud is up

Total bank frauds hit a record 43,000 in the first quarter, while credit card frauds surged to a record 118,000, according to the FTC. Delaware, a banking center, and neighboring Maryland are two of the top three states for bank fraud per capita, with over 500 reports per million people in both states so far this year, according to the FTC.

“Fraud schemes have certainly trended upward,” says Christine Davis, chief risk officer at WSFS, the largest bank based in the Philadelphia area. “We’ve had, I’d say, a triple increase in check washing over the past few years.”

When we reported the thefts from our account — before we heard from the postal inspectors — Davis’ colleagues asked if we’d lost any checks in the weeks before the fraud. I recounted that our April payment to Delmarva Power wasn’t cashed. We figured it maybe went astray within their system; my wife had made a replacement payment electronically and thought no more about it.

When that happens, “tell the bank,” said Davis. It will alert them to be extra vigilant on your account.

I should hope they’d be careful anyway. “Jordan” and “Karen” were careful — they made their six checks for different sums, $375 to $1,800, and apparently deposited them at unmanned ATMs, where they were swiftly honored through the convenient electronic process that allows banks to move your money around without paying live branch staff.

Davis apologized for taking a month to return my money after the bank’s errors. Sometimes it takes longer. “We have to work with another institution,” she said.

Some ways to protect yourself

The bankers are careful not to tell people to stop using checks. But “my guess is that your utility check was intercepted and duplicated,” said Michael Lawson, the retired Wilmington city police detective turned Artisans’ Bank official who chairs the Delaware Association for Bank Security.

“The best option to not get victimized again with check fraud is to stop writing checks and to pay all bills electronically,” Lawson added.

More people are indeed paying electronically. But technology helps thieves, too. “There’s a lot more messaging on social media now, about how to do this stuff,” said Clark, the postal inspector. “They tell you how to get your hands on checks: go through your grandparents’ dressers looking for old checkbooks, or steal them through the mail. They show you what gets flagged and what [looks authentic]. They tell you what chemicals to use to change details.”

Do banks urge Facebook or TikTok to take down these handy how-to guides, as they do with child pornography or bomb-making?

“The flow of information feels unstoppable,” said Clark. “Put a pin in one, there’s a billion more.”

ATM deposits are a convenience for people forced to deal with cash and checks at odd hours. But by taking away human staff, the process invites more thieves: “It’s intimidating to go and commit a crime when you have to deal with a person in front of you,” Clark said. But by committing fraud remotely, via smartphone banking, “you don’t feel like you’re dealing with anyone.”

In short, digital technology “discourages some kinds of thefts. It makes other theft easier,” concluded Clark.

Alas, the digital age hasn’t made people any more honest.