Fed pivots toward tackling inflation, forecasting three rate hikes in 2022

The Federal Reserve made its strongest move yet signaling a pivot toward tackling inflation on Wednesday, moving up the timeline for what policymakers project could be three interest rate hikes next year.

The Federal Reserve made its strongest move yet signaling a pivot toward tackling inflation on Wednesday, moving up the timeline for what policymakers project could be three interest rate hikes next year.

The change in policy, including a faster timeline for when the Fed will end its vast asset purchase program, marks a significant shift in how the Fed is responding to rising costs during the COVID-19 pandemic, and could affect everything from car loans to business investments in an effort to bring expenses for everyday goods and services under control.

Still, the Fed said that it will keep rates near zero, where they have been since the pandemic began, until the labor market makes enough progress to fall in line with what policymakers consider to be "maximum employment."

"Progress on vaccinations and an easing of supply constraints are expected to support continued gains in economic activity and employment as well as a reduction in inflation," according to a statement released at the conclusion of the Fed's two-day policy meeting. "Risks to the economic outlook remain, including from new variants of the virus."

Throughout the pandemic, the Fed's economic policy has been aimed at helping the labor market grow after the pandemic shut down the economy and wiped away millions of jobs. Now the Fed faces a major test as it falls under economic and political pressure to keep inflation in check without triggering consequences for the rest of the economy.

The Fed also announced on Wednesday that it will speed up the process of pulling back economic support for the financial system.

The faster timeline puts the Fed on track to fully wind down its vast asset purchase program by March, as opposed to the initial goal of mid-2022. The end of the so-called "taper" would then tee the Fed up to raise rates from near zero for the first time since the pandemic began.

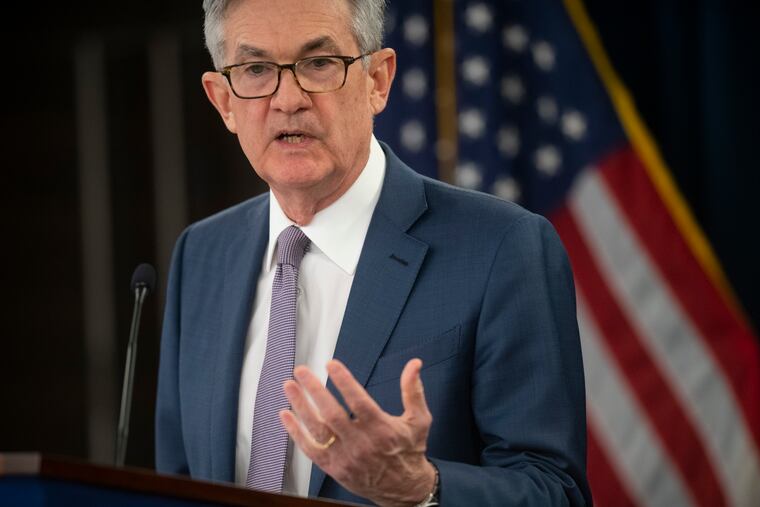

Fed Chair Jerome Powell said the U.S. economy is growing at a “robust pace” even as it faces risks from the pandemic, and he thinks spending by businesses and consumers will remain strong. But because inflation is likely to persist longer than the Fed had earlier expected, Powell said the central bank needs to address that threat to help the economy sustain its expansion.

“We will use our tools both to support the economy and a strong labor market and to prevent higher inflation from becoming entrenched,” Powell said at a news conference.

Fed officials on Wednesday released updated economic projections that offer a snapshot of the next few years. Policymakers expect inflation will drop off notably in 2022 but remain elevated at 2.6%. According to the projections, policymakers don’t see inflation falling all the way to the Fed’s 2% target by the end of 2023 or 2024.

At the same time, officials are forecasting continued growth in the labor market, where the jobless rate is currently 4.2%. Policymakers expect the unemployment rate will fall to a pre-pandemic level of 3.5% in 2022. That’s an improvement from the last round of projections, released in September, that put next year’s jobless rate at 3.8%.

The Fed's final meeting of the year comes as inflation rises to nearly 40-year highs and is increasingly spreading throughout the economy. For much of the year, Fed leaders said inflation would be temporary, or "transitory," and more limited to sectors hit hard by supply chain issues and other repercussions from the pandemic.

Over time, that message conflicted with the severity of inflation spreading further in the economy. Meanwhile, rising prices have become one of the most charged economic and political issues in a generation.

Prices have risen in just about every sector, from pork, poultry, and produce to housing and sporting goods, stretching the pocketbooks of households and businesses and eroding people’s optimism of how the economy overall is doing. Backtracking on earlier forecasts, Fed officials recently ditched their messages around temporary inflation and have worked to acknowledge that high prices are proving larger and more persistent than they expected.

The Fed's main lever for fighting inflation is through interest rates. Central bankers can raise of lower rates, depending on what they are seeing in the economy. Lower rates boost growth and help make the cost of business investment or loans cheaper. Higher rates limit that growth, in turn, have a cooling effect over the job market. Rates that are raised too sharply have the ability to spur a recession.

But that tool has its limits and operates with a lag. Rates affect the economy overall and cannot specifically bring down the sticker price for used cars or solve a broken supply chain.

Rising prices have also thrust the Fed into a heated political battle. Republicans blame Democrats' sprawling stimulus measures for overheating the economy and turbocharging consumer demand. GOP lawmakers and right-leaning economists also argue that Fed has been too slow to respond to widespread inflation and will ultimately be behind the curve once it decides to intervene.

Democrats say their stimulus measures were key to stabilizing the recovery, and they argue that their additional proposals to invest in jobs and infrastructure would bring down costs for working-class families over the long term. Much of President Biden's economic legacy could also rest on whether the Fed gets its policies right, and Biden's confidence in the Fed appears strong. In late November, Biden reappointed Powell to a second term as chair.

The Fed has two mandates — keeping prices stable and getting the economy to full employment. But combating inflation by raising interest rates can slow job market growth.

Throughout the pandemic, Powell has said the Fed won't pull back on its support for the economy until the labor market has healed. But it is unclear what the Fed considers to be "maximum employment," and what it has to see in the labor market to decide that threshold has been met.

By many measures, the job market has shown tremendous improvement. The unemployment rate fell to 4.2% in November, down from 4.6% in October. Since the Fed’s last policy meeting in November alone, two jobs reports showed the economy adding roughly 740,000 jobs.

However, some 4 million jobs are still missing from the labor market compared to pre-COVID days. Economists say they are hopeful that the coming months will continue to bring strong job gains, so long as the omicron variant or other unforeseen challenge don’t slow momentum.