Is FedLoan, America’s giant student loan servicer, running out of money?

America’s student debt crisis runs through Pennsylvania; new FedLoan CEO wants to start lending again

To understand why so many college graduates loathe the giant student loan servicer FedLoan, consider the experience of Megan Gammill.

The special-education teacher qualified for a $4,000 grant for tuition by teaching math in a poor public schools in Prince George’s County, Md., and Baltimore.

But when Gammill sent her grant recertification paperwork into FedLoan, as required, it was rejected. And as Gammill, 35, scrambled to fix it with calls and emails, the Harrisburg-based agency converted her TEACH grant into a $4,000 loan and told her the decision was irreversible.

Not willing to accept another $4,000 in debt, Gammill pleaded with the servicer, speaking to about 40 call-center employees and noting many of their company identification numbers over two years to get her grant recertified. Nothing worked. Gammill prevailed only after engaging a free attorney at the advocacy group Public Citizen.

“They are effectively stealing from teachers,” she said.

That’s been the experience of many borrowers dealing with FedLoan, part of the state-run monolith Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency (PHEAA) that services about 7.5 million federal student borrowers. The agency faces investigations from state attorneys general and a flood of complaints and lawsuits from disgruntled customers who believe that its customer service has cost them big bucks.

But now the giant loan collector is facing its own financial reckoning.

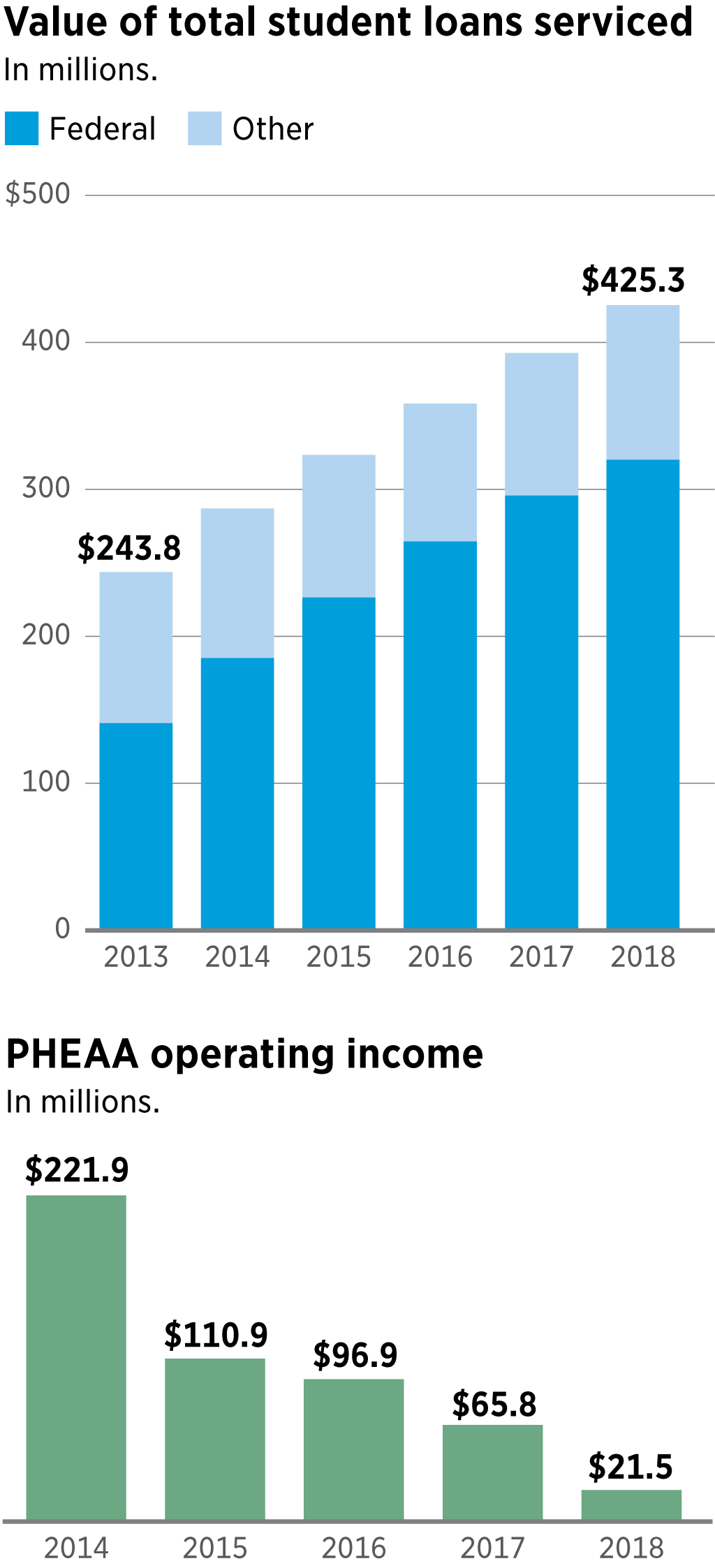

PHEAA’s profits have plummeted by 90 percent over the last four years. And the agency could soon start to lose money, in part because its servicing business has gotten so much harder, with new Congress-mandated loan options requiring more attention over the phone. The new CEO, James Steeley, who took over in January, has warned lawmakers that the river of cash that PHEAA has historically sent to Pennsylvania’s college grant program — about half a billion dollars over the last four years alone — is drying up and won’t be available in the future.

The tarnished agency now needs to reinvent itself, Steeley says, and the 41-year-old former bank comptroller has an audacious plan. He wants the loan servicing agency to become a loan originator, lending money directly to students as it did in the past. Steeley also has plans to reduce customer-service calls by using more smart-phone technology and upgrading IT systems.

State lawmakers — and PHEAA’s board, which is composed mostly of elected officials and governor appointees — are cautiously optimistic.

"We have to pivot and get it right,” said State Sen. Vincent J. Hughes, a Democrat who represents Philadelphia and Montgomery County and is a PHEAA board member. “I am hoping that over the next several months we really dive into this.”

But others predict more consumer angst and risk for taxpayers.

PHEAA will now borrow $50 million in 2019 to enter a crowded lending field with entrenched competitors. And its track record with such customers as Gammill makes it wholly unsuitable to be a lender, said Seth Frotman, the former student loan watchdog at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau who now runs the nonprofit Student Borrower Protection Center in Washington.

“Every family should be worried about taking a loan from a company that claims it is above the law," Frotman said, referring to PHEAA’s legal strategy that, as a state agency, it should be immune to lawsuits. “It’s not just that PHEAA is struggling to service federal student loans, like those in the Public Service Loan Program program. It also has a horrendous track record as a servicer for private student loans. A decade ago it got in bed with the biggest banks to create ‘the worst batch of student loans Wall Street ever bundled’ and, since then, as defaults have skyrocketed, it has routinely been accused of failing to produce basic documentation showing borrowers owe the debts being collected.”

Wayne Bremser, accounting professor at Villanova University, also expressed concerns after evaluating PHEAA’s finances at the Inquirer’s request.

“You look at how much risk the organization has, and it has increased a lot,” said Bremser, noting the declining income and the agency’s $50 million opening bet on lending. “They are facing some difficult challenges that will require resources for them to get [new loans to students] up and running. If you lose credibility with customers, they might stop coming back to you. Reputational risk makes people wary of you.”

Student debt cog

Americans owe about $1.5 trillion in college student loans. And as the Inquirer’s Debt Valley series has shown, the federal student loan system is rich in cash but poorly run, the default rate among students is growing, and the harm is especially apparent in Pennsylvania, where students graduate with some of the highest debt in the nation. State-supported colleges, such as Pennsylvania State University and Temple, charge tuition higher than those in other states, and the loan servicer PHEAA is a major cog in the nation’s byzantine college lending system.

Based out of a gray-stone, six-story mid-rise, a short walk from Harrisburg’s Capitol Building, PHEAA was created in 1963 to originate and service loans for the state’s students. It financed its own operations like a bank: borrowing money at prevailing interest rates and lending it to Pennsylvania students at higher ones.

But that changed drastically with the 2008 financial crisis.

Like most commercial borrowers, PHEAA found itself frozen out of debt markets. The U.S. government helped bail out banks by taking over responsibility for lending to college students through the U.S. Department of Education. But the federal government lacked a key function as the key student lender: how to service loans for millions of American borrowers with loan statements, calculating interest charges, principal reductions, tracking documentation, and many other tasks.

PHEAA presented itself as an answer. It services its loans for Pennsylvania students and those in other states.

It offered to do the same on a massive and more complex scale for the Department of Education. PHEAA bid and won the first of its federal contracts in 2009, branding its service as FedLoan.

PHEAA’s payrolls swelled to 3,000 employees as it opened call centers around the state — Chester and Pittsburgh, joining Harrisburg, Mechanicsburg, and State College — while creating an outsourced call center in Florida last year.

PHEAA today services $320 billion in student loans, or $1 in $5 of the nation’s student debt, and graduates know the servicer as FedLoan.

But the contracts came with strings. As Congress and the Department of Education responded to concerns over student delinquencies and defaults, they devised an expansive menu of repayment options through FedLoan, which added to servicing costs without raising the per-borrower fee paid to PHEAA.

More Loans Serviced, But Dwindling Profits

The Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency (PHEAA) services 20 percent of the nation's student debt. While the value of the loans it services has grown steadily, PHEAA’s profits have dropped sharply, due in part to federal regulations that added to servicing costs without raising per-borrower fees.

Value of total student loans serviced

In billions.

$425.3

$392.8

Federal

$358.4

$105.2

Other

$323.4

$97.0

PHEAA operating income

$287.0

$93.8

In millions.

$97.0

$243.8

$221.9

$101.8

$102.9

$320.1

$295.8

$264.6

$110.9

$226.4

$96.9

$185.2

$65.8

$140.9

$21.5

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Value of total student loans serviced

In billions.

Federal

Other

$500

$425.3

400

300

$243.8

200

100

0

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

PHEAA operating income

In millions.

$221.9

$110.9

$96.9

$65.8

$21.5

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

Lawsuits also exposed PHEAA to scrutiny, raising questions about the management of its loan-servicing operations. According to a 2013 suit filed in federal court in Richmond, Va., PHEAA had no formal procedures to investigate, report, or deal with identity theft.

Plaintiff and victim Lee Pele first learned that his identity had been stolen for two student loans amounting to $137,000 after a debt collector called him. In a deposition, Pele’s lawyer, A. Hugo Blankenship, elicited that the PHEAA employee who wrote the agency’s manual for “default collections” wasn’t an expert in debt collection, but was instead a high school graduate who had gone to trade school for massage therapy.

Asked why she was chosen to write the manual on default collections, she responded: “I have no idea.”

PHEAA settled the case, Blankenship said. Terms weren’t disclosed.

Last year, five federal lawsuits against PHEAA and FedLoan alleging a host of servicing problems were consolidated in federal court before U.S. District Judge C. Darnell Jones II in Philadelphia. The suits claim that PHEAA has posted misleading information on its website, fails to respond to complaints and process forgiveness applications, puts borrowers into repayment plans without consent, or improperly places them in deferment, letting students temporarily stop or temporarily reduce federal loan payments.

‘Jaw-dropping’

In August 2017, Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey filed suit in state court, alleging that PHEAA’s had failed to service the Public Service Loan Forgiveness and TEACH grant programs, in violation of Massachusetts and federal law. PHEAA has the nation’s exclusive contracts to service these two loan-forgiveness programs.

PHEAA’s failures “have harmed Massachusetts student borrowers, depriving them of months that should have counted toward their loan forgiveness, causing them to lose financial grants, and saddling them with debt,” the Massachusetts suit says. The case is still in litigation.

In Kentucky, PHEAA fought the production of documents for that state’s attorney general investigation, claiming it has sovereign immunity as an arm of the Pennsylvania government.

“It’s a jaw-dropping claim if they are right about that,” said Ben Carter, an attorney with the Kentucky Equal Justice Center, an advocacy group that has intervened in the case. “Every state could start a bank and immunize it and open a branch in another state and then claim it can’t be investigated.”

The former federal regulator Frotman calls PHEAA’s immunity claims “outlandish.”

“It’s imperative for residents of Pennsylvania to say they’ll no longer tolerate this massive financial services entity behavior in their name,” he added.

More than 7,000 complaints have been filed against PHEAA at the Consumer Financial Protection Board since 2012, when the database was launched. But the CFPB itself has been defanged under the Trump administration and his secretary of education, Betsy DeVos.

An additional 1,000 people complained to PHEAA itself over the last three years, according to data obtained by an Inquirer Right to Know Request.

The only student loan servicer with more complaints is Wilmington-based Navient Corp., which has 17,000 complaints and runs a big call center in Wilkes-Barre. Navient is now fighting off a proxy battle by an activist hedge fund.

‘Not sustainable’

PHEAA spokesperson Keith New rebuts sharp criticism of the agency’s customer servicing, saying 99 percent of its borrowers are happy and haven’t complained to its hotline or the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau.

CEO Steeley said FedLoan’s customer complaint metrics are distorted by the two programs for which FedLoan has exclusive contracts.

These contracts — the TEACH program (the one for which Gammill was eligible) and the Public Student Loan Forgiveness program — can have complex issues. The latter program offers forgiveness for public defenders, nurses, first responders, and others working for qualifying nonprofits, after 120 consecutive payments.

Mistakes can reset the clock on earning loan forgiveness, which can add months or years of payments.

“Especially with Public Loan Forgiveness, often borrowers are coming to us after they have been with other servicers that don’t really know the rules of the program," Steeley said.

“So then suddenly we’re the ones telling them that, ‘oh, your prior servicers didn’t have you on the right repayment plan for the last seven years.’”

The basic problem with the servicing business, Steeley said, is that the Department of Education doesn’t pay enough for what it now requires of servicers, a concern echoed by the publicly traded Navient.

Based on public data, the education department pays the equivalent of about $70 to service every $10,000 in federal student loans. By comparison, commercial banks earn about $250 in servicing fees for every $10,000 in mortgages, industry sources say. And home mortgages are simpler to service because they lack the complex repayment options for student debt.

Steeley said the agency views itself as engaged in a public-service mission to help college students and it doesn’t have the same Wall Street pressures as the publicly traded firms, such as loan-servicer NelNet or Navient, which answer to shareholders.

PHEAA contributed 27 percent of the funds in Pennsylvania’s tuition grant program this fiscal year, or $101 million of the $374 million program. More than 100,000 Pennsylvania students got grants up to $4,123.

This is money that PHEAA can no longer afford to pay, Steeley said.

In his budget, Wolf has proposed increasing the state contribution to the state grant but not enough to offset the loss from PHEAA. Lawmakers will have to decide if they will cut the size of the grants.

Steeley’s plan to lend again needs a stake. So PHEAA has gotten state approval to issue $50 million in tax-free agency bonds in 2019, and can request more, if needed.

Outside experts are skeptical of PHEAA’s reinvention plan.

“I would be cautious of anyone’s plans to make big inroads into the private student lending market,” said Moshe Orenbuch, analyst with Credit Suisse Securities who covers PHEAA competitor Navient Corp. Lending for college “is not a simple business.” Competitors such as Sallie Mae, Discover, Wells Fargo, and start-ups such as like College Ave are striving for the same borrowers, marketing themselves on social media and the internet.

“You have to get the parent to pick you,” and then the lender has to fairly consider the borrower’s credit risk and likelihood of repayment, Orenbuch said.

Steeley says he is undaunted, and that the time for action is now.

PHEAA has already dipped as far into its reserves as he is financially comfortable, Steeley said.

“At the end of the day, the state owns us. It’s their prerogative, but there’s the potential and I think this is understood that [the current model] is not sustainable,” Steeley said. “We’ve given close to a half-billion dollars away out of our earnings and reserves over the four most recent budget cycles” to the state’s loan grant program, he said.

“We’re basically at a point that our own internal metrics are saying that at the end of the current fiscal year, our reserves are going to be at what we’ve established as our floor.”