After the bailout: Goldman Sachs wants to be America’s mass-market bank

“Just put one dollar in front of the other,”urges an ad, promoting the company’s Marcus deposit accounts, named for Marcus Goldman, who founded the firm in 1869.

Goldman Sachs, the famously lucrative financial adviser to governments and corporations, whose boss once described its investment strategy as “long-term greedy,” is now going after the middle class.

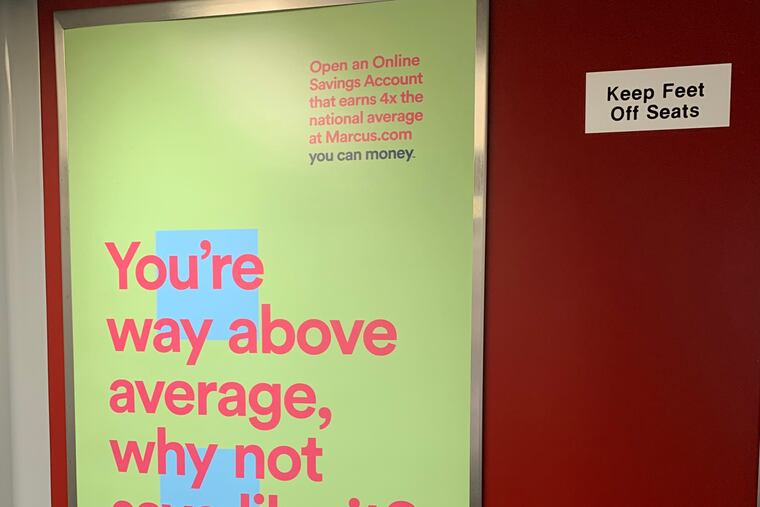

“You’re way above average, why not save like it?" urges a Goldman ad on Septa commuter trains. “Just put one dollar in front of the other,” urges another, all promoting the company’s Marcus deposit accounts, named for Marcus Goldman, who founded the firm in 1869.

The company is also reaching out to the working and saving masses through direct mail, print and video ads, and even billboards, reversing a long period in which, if you had to ask where Goldman Sachs was, you didn’t belong there.

Like Vanguard Group, the $5 trillion-asset Malvern money manager which has expanded faster than its rivals, Goldman is going mass market by relying on technology and attractive pricing -- without an expensive network of brick-and-mortar retail branch offices.

That’s in contrast with its New York rival, JPMorgan Chase & Co., which has pledged to build 50 branches in the Philadelphia area by 2024 and hundreds in other targeted cities in a bid to sell more stuff to its mortgage and credit-card borrowers. (New York-based Citigroup tried a similar effort in the late 2000s, then shut the branches down, writing off milllions in sunk costs.)

Of course, Vanguard has been burnishing its reputation for low-fee retirement savings since its founding in 1975. But for Goldman, whose longtime Philadelphia branch chief, the late George Ross, grew rich from government bond fees (and led the charity campaign to build the city’s National Museum of American Jewish History), seeking a rep as banker-to-the-people marks a big expansion, and even a reversal, of its image.

Indeed, at Goldman Sachs, traditionally “we don’t advertise,” says Ross’s successor, managing director Nicole Ross (no relation to George), who among other duties oversees the company’s century-old Philadelphia wealth-management office, now based in the BNY Mellon Center on Market Street.

For Goldman’s wealth-management and investment-banking businesses, no logos adorn its buildings, let alone billboards. “When we do a great job, they will tell their peers,” Ross added.

For Ross’ end of Goldman’s business, which helps millionaires and private-equity financiers buy into such investments as Facebook or Uber before they are publicly traded, and fields 3 a.m. calls from heirs with tax questions, “our average client has about $50 million with us," and knows how to put his or her own advisers in touch with the firm’s reps without having to copy the Web address on public transit.

Goldman’s mass-market move was made possible by its agreement 10 years ago, after a $10 billion government bailout amid the mortgage-finance crisis (which it repaid, with interest), to seek bank-funded, federally administered FDIC deposit insurance and a commercial banking charter. That made Goldman more like JPMorgan, Wells Fargo, and local banks that can raise money cheaply by paying low rates to depositors in need of safe places to stash cash.

However, the bank moved slowly to exploit that power: “It took the firm several years to come to the conclusion that we really are a [commercial] bank," said Dustin Cohn, newly promoted brand-marketing chief for Goldman Sachs’ Consumer and Investment Management Division.

(Marcus’ head of product, Michael Cerda, was recruited from Facebook in early 2017, among a wave of high-profile bank recruitments of Silicon Valley talent -- but departed in April for a job at Disney, closer to his California home, according to the Financial Times.)

Goldman started its populist move in 2016 by offering small personal loans, similar to credit card loans, from $3,500 to $40,000. Like Wilmington-based Best Egg (corrected) and other “fintech” companies that offer fast, low-hassle lending to people whose credit can be checked from their consumer data, Goldman sought to design a business that could be profitable even in its early stages, and which solved what Cohn called “consumer pain points,” such as deposit limits and withdrawal penalties, by not requiring any.

“We see ourselves as a technology company, and knew we could build it from scratch for a good user experience, without bricks and mortar,” said Cohn. Goldman’s deposits group is in Chicago (corrected), its tech group in California.

Marcus’ listed unsecured loan rates currently start at about 6 percent. That’s competitive with standard credit card rates, which average from 17 percent to 26 percent -- even for borrowers with “excellent” credit and top Fair Isaac & Co. (FICO) scores, according to Bank Rate Monitor. In three years, the company has built up a portfolio of $5 billion in small loans, Cohn said.

In the last two years, the company has also solicited deposits, paying 2.25 percent a year, with no minimum balance and no term -- with slightly higher rates for longer-term commitments, but no penalties for early withdrawal -- and attracted $45 billion in the U.S. and U.K.

The Marcus accounts also allow users to arrange automatic bill payment -- unlike Vanguard, which recently discontinued that service for most investors.

While banks and investment firms such as Vanguard have been upgrading their automated customer service, Marcus brags about human customer service, from call centers in Utah and Texas. “To be a digital business, people need to trust you, and that means having the opportunity to speak to a live person, not a machine,” said Cohn.

Goldman even tries to turn its lack of retail branches into a virtue: Cohn insists, in contrast with JPMorgan data showing that millennials actually visit bank branches almost as often as old people, that “most people hate bank branches.”

Goldman recently scored a coup over its mass-market rivals when it beat out JPMorgan Chase & Co., Citigroup and other lenders to issue MasterCards for Apple. Goldman said it could offer a simple card with attractive rates and limited fees.

The history of the credit card business is littered with retailer card programs that grew fast but proved unprofitable as borrowers stopped paying. Goldman Sachs now gets a chance to show whether it can transfer its high-end expertise at handling wealth, and its recent success at attracting deposits, to mass-market credit decisions -- and make enough money to please Apple as well as its own shareholders.