Joe Biden’s politics can be explained by Delaware’s shadowy past

Delaware is a lot more like the U.S. than early-voting Iowa or New Hampshire. Biden’s rise says a lot about how Democrats can win and lose.

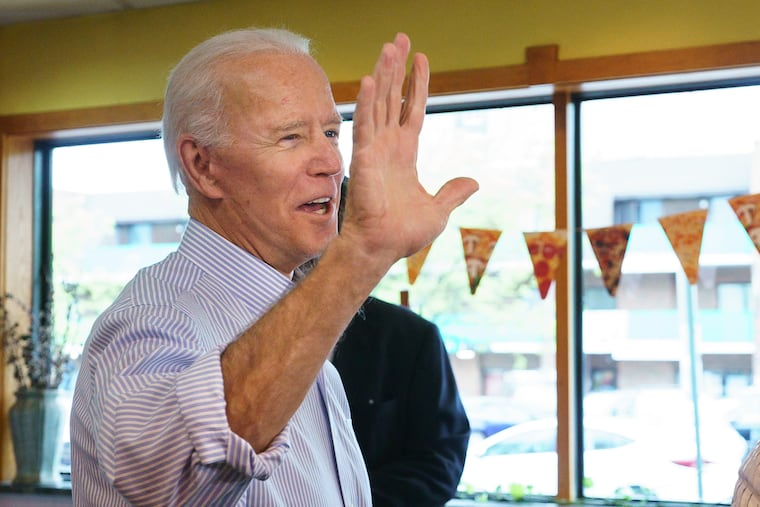

Whether he remains the front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination or fades back into retirement, former Vice President Joe Biden is the most successful politician to come out of Delaware.

With its mixed economy and populations, Delaware is a lot more like the U.S.A. in miniature than the early-voting states of Iowa or New Hampshire. How did Biden rise there, and what does it say about his national appeal, and its limits?

In the early 1970s, consumer advocate Ralph Nader called Delaware “the Company State” and sketched how its government, economy, politics, and even charities were dominated by the DuPont Co. and a Republican corporate-paternal tradition.

But as that company declined and fragmented, Biden’s generation of Delaware Democrats built a broad voting coalition and a multistate fund-raising machine that has placed Democrats in control of state government and every statewide office, including both U.S. senators and lone U.S. Rep. Lisa Blunt Rochester, one of the few African American women representing a majority-white district in Congress.

If all they cared about was winning, Delaware might offer Democrats a road map.

But Biden’s more liberal Democratic critics are using the planks in his long Senate record to whack him. What use is it electing D’s, they ask, if you end up with old guys such as Biden, who was friendly with segregationists in his long Senate career, questioned the wisdom of court-ordered school integration, and worked with Wall Street bankers to squeeze consumers?

There are dark shadows in Delaware’s long history: The state was the last to abolish public whipping, hanging, and slavery. How did Biden approach a state like that?

‘Forced busing': Into the 1960s, Delaware had unequal black and white public school systems. A parent lawsuit against that system was combined into the landmark Brown v. Board of Education case in which the Supreme Court ordered an end to school segregation.

A federal judge rejiggered school districts in the Wilmington area where most Delawareans live, so each stretched from the black city center to the white state line, and ordered that schools balance enrollments, white and black.

Sam Waltz, who headed the Wilmington News Journal’s state capital bureau and covered Biden in the mid-1970s, says the elementary school in his suburban neighborhood, North Star, was one of several shut under the court order so his three kids and their neighbors could be “bused nearly an hour into the city. Even as a lifelong Democrat involved in civil rights, I didn’t like it. It was a federally

imposed judicial solution.”

Was this a moment for a real leader to back the law even if it meant alienating some parents? “Many of us characterized Joe Biden as a 'Ted Kennedy liberal’ — but he was also a politician who could count, and he wasn’t going against a mass of his white supporters to endorse ‘forced busing,’” Waltz said.

‘Charm and b.s.:’ In Congress, Biden approached the segregationist senators who controlled key committees, made friends, and got ahead. In the Senate, “you’ve got to see things from the other guy’s point of view, and Joe mastered that," from the time he took his seat in 1973, aged 30, Waltz said. Like Bill Clinton, he pushed mandatory-sentencing prison legislation to show he was “hard on crime,” boosting support among white Democrats who otherwise backed Reagan, or Trump.

"Joe Biden is not a ‘blow-up-the-house politician,’” not like Trump, or even Obama, Waltz concludes. He’s “Irish charm and b.s.” The challenge for Biden was to keep his suburban white supporters without alienating the black voters who gave Democrats their statewide margins.

Where else could they go? By the time I worked at the News Journal in the early 1990s. black leaders in Wilmington wanted to reconstitute an urban school district where residents had more power. Instead of allowing that potentially divisive split, Democrats focused on boosting school funding, and diversity hiring, and making it easier to start charter schools, moves that helped keep their coalition dominant.

Payback: Biden was also among the Democrats who joined Republicans in giving credit card and student loan lenders what they wanted — laws limiting bankruptcy write-downs for people who borrowed more than they could pay and contributing, some economists say, to the late-2000s financial crisis. Those laws also fueled student debts that have made it tough for many young people to buy homes.

Biden became friendly with the late Charles M. Cawley, who built Maryland National Bank’s credit card arm into Delaware’s largest private employer, MBNA, now part of Bank of America. Biden bought his sprawling Greenville, Del., home from an MBNA executive at an attractive price. Bankers gave generously to Biden’s campaigns and hired his son.

Isn’t that selling a public office? Biden — like other Delaware Democrats, including current U.S. Sen. Tom Carper — could argue that he was boosting hometown employers and keeping University of Delaware grads in the state as DuPont and other old industries were cutting back.

Student lenders Sallie Mae and Navient followed the big card banks in moving to Wilmington and hiring thousands. (Biden’s son and political heir Beau Biden took a more aggressive anti-bank line when he was Delaware’s attorney general. The younger Biden died of cancer four years ago.)

None of this is new, including the outrage. “Progressive types” were critical of Biden back in the day, says Gary Hindes, the former Delaware Democratic chairman who has made his Delaware Bay Co. clients rich suing the government for botched corporate bailouts. "At the end of the day, most come to realize that in politics, you can’t allow the perfect to get in the way of the good.” A favorite Obama saying.

Hindes speaks for that kind of finance and business Democrat, accustomed to winning by checking the people’s pulse, and not running too far ahead: “Joe is our best shot at beating Trump."

He worries the U.S. senators and local politicians who are Biden’s early rivals “aren’t yet ready for prime time. We’d better ride our best horse lest we end up with another ‘fluke’ election. The country — at least the 60 percent who do not support Trump — simply cannot afford to take that chance.”