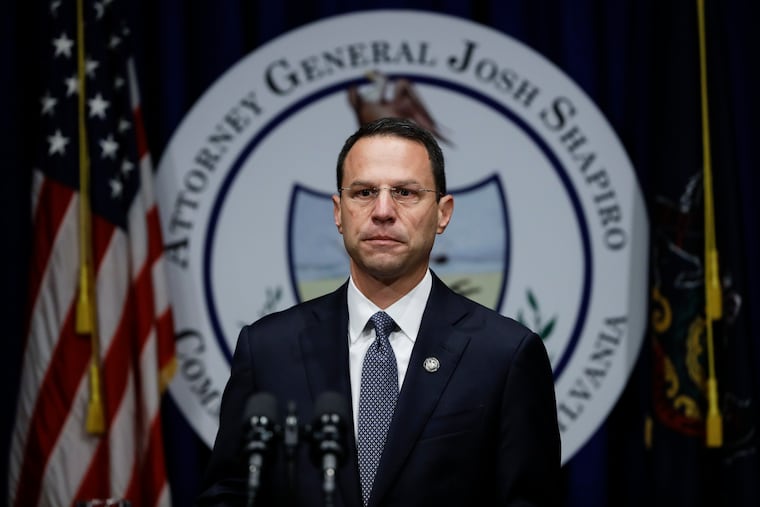

AG Josh Shapiro’s legal fight vs Navient, for-profit colleges heats up in Pa. | Debt Valley

Pa. is ground zero for student loan debt, and Attorney General Josh Shapiro is suing Navient Corp. one of the largest loan servicers, alleging that debtors were mislead and defrauded.

Under Trump appointee Mick Mulvaney, the nation’s federal consumer protection agency has backed off its regulatory role. In its place have stepped some state attorneys general, including Pennsylvania’s Josh Shapiro.

His lawsuit against Navient is one of about a half dozen around the country against the student-loan servicer. So why is he picking up the mantle of the defanged Consumer Financial Protection Bureau?

Because the state is ground zero for student-loan debt,

First, some context: In December, Shapiro notched what his office called a “big win” in the AG’s lawsuit against Navient, one of the nation’s biggest loan servicers, with offices in Wilkes-Barre and Delaware. U.S. District Judge Robert Mariani dismissed Navient’s motion to dismiss the case, in particular one argument that states can’t bring claims when there is already a pending lawsuit by a federal agency. Notably, Navient also faces similar suits from Illinois, Washington, California, Mississippi, and the CFPB itself, filed in the last days before President Donald Trump took office.

Shapiro’s lawsuit alleges that Navient offered predatory loans to college students with poor credit. These students attended colleges with a low graduation rate. Ultimately, many borrowers were not able to repay their loans, or were steered away from better repayment plans, the suit says. Navient allegedly pushed borrowers into short-term repayments instead of helping them enroll in plans that cap payments relative to income, as Congress has mandated to help prevent graduates from defaulting.

The judge ruled in December that Pennsylvania’s case against Navient could move forward. In his 70-page opinion, Mariani called Navient’s arguments “creative, [but] they do not convince the Court” that state enforcement actions can’t be filed alongside a federal suit.

So why focus on the suit and what happens now?

“We have the second-highest debt burden in Pennsylvania” in the nation, at about $36,000 per student, Shapiro said in an interview.

“That limits students and their families, and the choices they make," he said. "Young people come up to me and say, ‘I want to be doing x, but I have these loans, so I have to do y.’ That limits our economy as a commonwealth. It holds us back from someone innovating and taking risk.”

Second, “layer on top of that lenders who are unscrupulous, scamming loan-holders, and the federal government under Trump and [Department of Education secretary Betsy] DeVos rolling back protections for students and their families — you’ve created an environment that’s anticompetitive and tilted against students and their families.”

Navient Corp., one of the biggest servicers of U.S. student loans, is sharing student-loan information, known as “discovery,” with Shapiro’s office. Navient is the nation’s third-largest loan servicer, serving about 22 percent of federal and private loans. PHEAA and Nelnet-Great Lakes are the two largest.

What are the AG lawsuit’s main claims against Navient?

“They were doing two things: One, as relates to for-profit colleges, they were entering into these loans that were basically payday loans designed to curry favor with for-profit institutions," Shapiro said. “They charged students more than needed. They wanted to become the preferred lender for the for-profit colleges.”

Second, when students fell behind, “if they fell ill, or they lost a job, and called up Navient to say, ‘Under federal guidelines, I’m entitled to some relief. I can make a payment based on my income.’ Instead they were being steered into forbearance, and essentially told, don’t make a payment right now. Come back when you’re ready.' "

“The effect of that? It added a total of $4 billion worth of additional debt statewide on these students who otherwise would have qualified for lower repayments. They were never told about that or were steered elsewhere,” Shapiro contends.

Because Navient has a major facility in Wilkes-Barre, Shapiro says he’s arguing the case on behalf of Pennsylvania students as well as “anyone whose loan is serviced there, including anyone across the country.”

Navient calls the AG’s filing “false” and a “copycat suit” of the CFPB case filed in late 2016, and laid out a point-by-point rebuttal at Navient.com, and in other statements and legal filings.

“Navient’s own discovery efforts have been largely focused on finding out what evidence the CFPB has to support the allegations that have been made against Navient, which have caused significant reputational and economic damage to the company, its shareholders, and its employees," Navient said in a statement.

Navient says it is a leader in enrolling eligible borrowers into income-driven repayment (IDR) programs, and also has no incentive to put borrowers into forbearance — time off from paying — because it gets paid less for that than for standard repayment plans.

The current rules are stacked against income-driven repayment, according to Navient, since many borrowers are required to pay in full before entering into such an arrangement; others make too much money. Graduates who miss payments must pay the total past-due balance. Second, borrowers may need forbearance to enroll in IDR to get payment relief during the time it takes to complete the government-mandated application without becoming further past due, Navient said last June.

As recently as Jan. 17, Navient filed a motion in the CFPB case, arguing that claims of Navient improperly “steering” students “fail because the calls with the identified borrowers demonstrate that Navient’s practice was to inform borrowers … over the phone. In fact, it is undisputed that all but one of the deposed borrowers discussed IDR with Navient representatives. Yet some still chose not to apply.”

Navient also pointed to testimony from Jason Delisle of the American Enterprise Institute, who said in 2018 that "the way the program is set up, the best option for borrowers is forbearance because it doesn’t require any paperwork and it immediately cures the loan, and doesn’t require the borrower to do anything. … Here we have all the advocacy groups and the press out there saying, ‘These terrible servicers!' But meanwhile, there’s no criticism of the design of these policies and the policymakers making them.”

Critics contend that Shapiro embraced the student-loan crisis as a political issue on which to run for higher office. Charlie Gerow, a Harrisburg-based Republican strategist, said Shapiro is “taking a playbook handed to him by the national Democrats.”

Shapiro said he first became interested in college affordability when he was representing Montgomery County as commissioner years ago.

“When I was county commissioner, I passed a dedicated [property] tax for our Montgomery County Community College to bring down tuition costs," he said. "Community colleges are critically important, because usually 90 percent of graduates stay in the state and 70 percent stay in the county. They have a massive economic impact.”

Before state cuts, the college received roughly one-third of its funds from the county, state, and tuition. By the time Shapiro became commissioner, that ratio was 20 percent county, 20 percent state, and 60 percent tuition, he said.

“It was upsetting. The state was ratcheting back. We needed to get the Montco share back up,” so the entire tax went to the college.

In addition, once he became AG, Shapiro created his own consumer financial protection unit, hiring a top executive from the CFPB, Nicholas Smyth, to run the unit. Its focus is for-profit colleges such as Brightwood, which shuttered suddenly and without warning in late 2018.

“We’ve opened up an investigation, and we’ve received complaints from Brightwood students” in Pennsylvania, where roughly 1,500 students attended, Shapiro said. Roughly 35 students have filed complaints.

Student borrowers who believe they have been subject to unfair or deceptive practices can file a complaint with the Office of Attorney General at www.attorneygeneral.gov. They can also call 800-441-2555 or email scams@attorneygeneral.gov.

Also, students should contact the Pennsylvania Department of Education if they have a federal loan for a school that’s closed, said Joe Grace, Shapiro’s spokesperson. The website is: www.education.pa.gov.

Meanwhile, Navient is facing similar lawsuits brought by the attorneys general of Illinois, Washington, California, and Mississippi.

What might a settlement look like? In 2016, Navient was prepared to pay $1 billion to settle a three-year investigation by the CFPB over claims that the company misled borrowers and made other mistakes servicing federal loans, according to the New York Times. But the settlement broke down after Trump was elected president in late 2016 and the agency signaled it would loosen the industry’s regulations, the New York Times reported.

Shapiro wouldn’t be drawn in on any potential settlement details.

“In a typical consumer case, we might enter into an agreement with a financial penalty," he said. “We agree the company owes money and takes steps to change corporate behavior. The company might also say, ‘OK, we’re prepared to settle, we want all the other states to be a part of it too.’ That’s how this could happen. It could also happen through the courts. A judge metes out a ruling saying, ‘You owe X and stop doing A, B, and C,' ” Shapiro said.

Another model might be the nationwide settlement just agreed to with the for-profit Career Education Corp. CEC wiped out $493.7 million in debts owed by 179,529 students nationally in a settlement with 49 attorneys general in January. Shapiro’s office said the settlement meant 12,600 Pennsylvania students who attended schools affiliated with CEC will have $38.6 million in student-loan debts relieved.

CEC operated three now-closed schools in Pennsylvania — one each in Philadelphia, Pittsburgh, and Wilkins, just outside Pittsburgh. The schools operated under the name Sanford-Brown College.

Meanwhile, Pennsylvania student debt continues to grow: According to data compiled by LendEDU, average debt per student rose from $35,185 in 2017 to $36,193 in 2018. And roughly two-thirds of Pennsylvania graduates leave school with college debt.