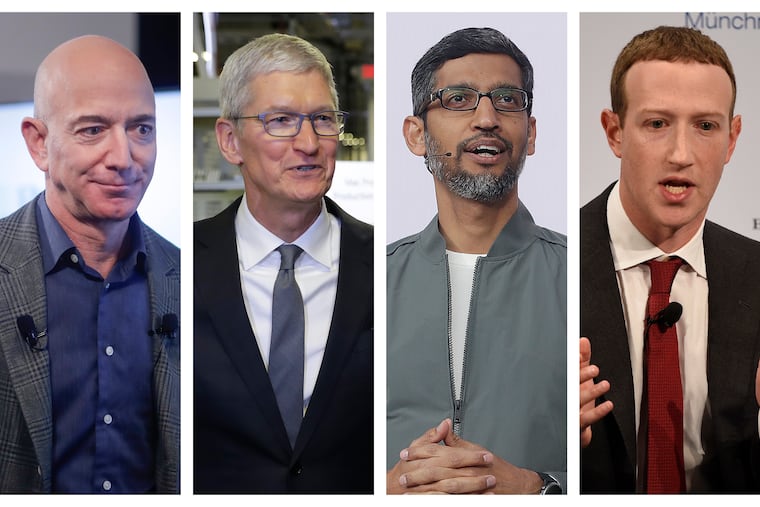

Four Big Tech CEOs take heat from Congress on competition

CEOs from Aamzon, Facebook Google and Apple provided bursts of data showing how competitive their markets are, and the value of their innovation and essential services to consumers.

WASHINGTON — Fending off accusations of stifling competition, four Big Tech CEOs — Facebook’s Mark Zuckerberg, Amazon’s Jeff Bezos, Sundar Pichai of Google and Tim Cook of Apple — are answering for their companies’ practices before Congress as a House panel caps its yearlong investigation of market dominance in the industry.

The powerful CEOs sought to defend their companies amid intense grilling by lawmakers on Wednesday.

The executives provided bursts of data showing how competitive their markets are, and the value of their innovation and essential services to consumers. But they sometimes struggled to answer pointed questions about their business practices. They also confronted a range of other concerns about alleged political bias, their effect on U.S. democracy and their role in China.

The four CEOs were testifying remotely to lawmakers, most of whom were sitting, in masks, inside the hearing room in Washington.

Among the toughest questions for Google and Amazon involved accusations that they used their dominant platforms to scoop up data about competitors in a way that gave them an unfair advantage.

Bezos said in his first testimony to Congress that he couldn’t guarantee that the company had not accessed seller data to make competing products, an allegation that the company and its executives have previously denied.

Regulators in the U.S. and Europe have scrutinized Amazon’s relationship with the businesses that sell on its site and whether the online shopping giant has been using data from the sellers to create its own private-label products.

“We have a policy against using seller-specific data to aid our private label business,” Bezos said in a response to a question from U.S. Rep. Pramila Jayapal, a Washington Democrat. “But I can’t guarantee to you that that policy hasn’t been violated.”

Pichai’s opening remarks touted Google’s value to mom-and-pop businesses in Bristol, R.I., and Pewaukee, Wisc., in the home districts of the antitrust panel’s Democratic chairman, Rhode Island Rep. David Cicilline, and its ranking Republican, Rep. James Sensenbrenner of Wisconsin.

But the Google executive struggled as Cicilline accused the company of leveraging its dominant search engine to steal ideas and information from other websites and manipulating its results to drive people to its own digital services to boost its profits.

Pichai repeatedly deflected Cicilline’s attacks by asserting that Google tries to provide the most helpful and relevant information to the hundreds of millions of people who use its search engine each day in an effort to keep them coming back instead of defecting to a rival service, such as Microsoft’s Bing.

As Democrats largely focused on market competition, several Republicans aired longstanding grievances that the tech companies are censoring conservative voices and questioned their business activities in China. “Big Tech is out to get conservatives,” said Rep. Jim Jordan of Ohio.

In a tweet before the hearing, President Donald Trump challenged Congress to crack down on the companies, which he has accused, without evidence, of bias against him and conservatives in general.

“If Congress doesn’t bring fairness to Big Tech, which they should have done years ago, I will do it myself with Executive Orders,” Trump tweeted.

Executive orders are more limited in scope than laws passed by Congress, though they too have the force of law. But presidents can't use executive orders to alter federal statutes. That takes congressional action.

Trump's Justice Department has urged Congress to roll back long-held legal protections for online platforms such as Facebook, Google and Twitter. The proposed changes would strip some of the bedrock protections that have generally shielded the companies from legal responsibility for what people post on their platforms.

The four tech CEOs command corporations with gold-plated brands, millions or even billions of customers, and a combined value greater than the entire German economy. One of them, Bezos, is the world’s richest individual; Zuckerberg is the fourth-ranked billionaire.

Critics have questioned whether the companies stifle competition and innovation, raise prices for consumers and pose a danger to society.

In its bipartisan investigation, the Judiciary subcommittee collected testimony from mid-level executives of the four firms, competitors and legal experts, and pored over more than a million internal documents from the companies. A key question: whether existing competition policies and century-old antitrust laws are adequate for overseeing the tech giants, or if new legislation and enforcement funding are needed.

Cicilline has called the four companies monopolies, although he says breaking them up should be a last resort. While forced breakups may appear unlikely, the wide scrutiny of Big Tech points toward possible new restrictions on its power.

Cicilline also said that in the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, “these giants stand to profit” and become even more powerful as millions shift more of their work and commerce online.

The companies face legal and political offensives on multiplying fronts, from Congress, the Trump administration, federal and state regulators and European watchdogs. The Justice Department and the Federal Trade Commission have been investigating the four companies’ practices.

Associated Press reporters Michael Liedtke in San Ramon, California, Joseph Pisani in New York and Matt O’Brien in Providence, Rhode Island, contributed to this report.