Millions in assets have been found to pay back Par Funding investors as settlement inches closer

Investigators working for the court-appointed receiver say they have found most of the estimated $250 million needed to repay investors.

Three years after taking control of Philadelphia-based Par Funding, investigators working for its court-appointed receiver say they have found most of the estimated $250 million they would need to repay investors, who pumped money into the high-risk loan company before its owners were hit with federal civil and criminal fraud charges.

Attorneys and accountants for receiver Ryan Stumphauzer began searching for cash and physical assets the government said were wrongly acquired by Par’s owners at investors’ expense following a 2020 lawsuit filed by the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission and FBI raids on the company’s offices and owners’ homes that year.

Par was an important player tied to other firms in the loosely regulated, multibillion-dollar merchant cash advance industry. The SEC civil complaint and more recent criminal fraud complaints have focused less on Par’s small-business borrowers, who paid high rates of interest because they couldn’t qualify for mainstream bank loans, and more on what the government says was the fraudulent sale of unregistered securities to investors, which were used to finance Par’s loans.

At a hearing in Miami on June 29 before U.S. District Judge Rodolfo Ruiz Jr., lawyers for the receiver gave an update on the assets they have arranged to use to repay investors and said they hope to begin repayments later this year.

But first they have to settle with Dean Vagnozzi, a King of Prussia investment salesman who attracted hundreds of people to invest in Par but says he was himself a victim — of bad advice, from his longtime lawyer at a Philadelphia corporate law firm.

Assets identified by the receivers’ lawyers include:

$123 million in cash collected from Par owners Joseph LaForte and his wife, Lisa McElhone; from their accountant Joseph Cole Barleta; from owners of investment sales firms that sold investments for Par; and from Par’s own borrowers.

$45 million from a proposed settlement with Eckert Seamans Cherin & Mellott, LLC, a Philadelphia-based law firm that has been sued by Par investors for failing to stop former partner John Pauciulo from blessing the sale of unregistered Par securities while he was an Eckert partner in the 2010s and early 2020s and failing to warn investors about the risks.

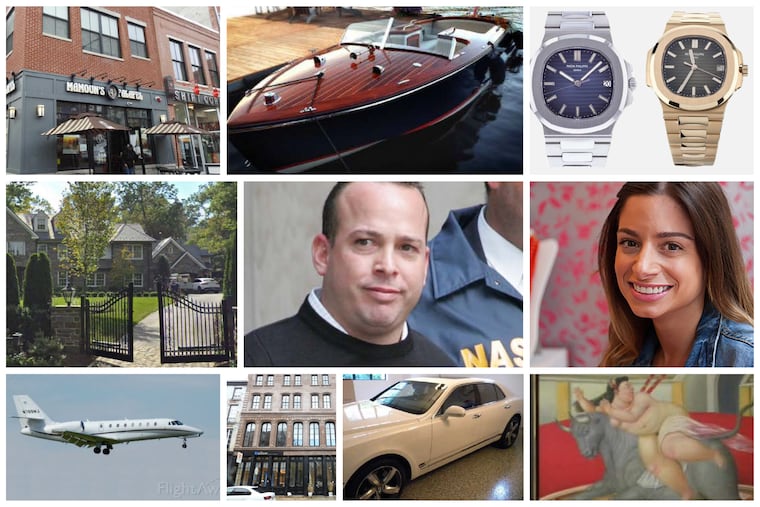

$15 million or more from the pending sales of two of the LaFortes’ former residences — in Jupiter, Fla., and at Paupack in the Poconos — both of which attracted offers above their asking prices. Their former primary residence, a Haverford mansion, sold for $3.4 million in May. The Jupiter property is expected to sell for about twice the $5.8 million the couple paid for it four years ago.

An estimated $44 million worth of Philadelphia real estate, including 22 properties that together house 11 store or office spaces and 110 apartments.

At least $3 million for nine cars, six Jet Skis, two boats, Rolex watches, paintings, and other items seized from the LaFortes and their associates by the receivership, which are to be sold to raise cash for investors. That doesn’t include the LaFortes’ former jet, worth an estimated $8 million when it was seized by the FBI three years ago and still in federal custody.

In May, Par Funding and its principals were criminally charged with committing fraud that fleeced investors out of as much as $550 million and making Mafia-style threats of violence to its business customers. Two Par Funding employees, former salesman Perry Abbonizio and debt collector Renato “Gino” Gioe, have pleaded guilty to criminal charges stemming from their work for the company.

Prosecutors hope to collect additional money using a separate property seizure, sale, and restitution process. “We are coordinating with the U.S. Attorney’s Office and the FBI [in] Pennsylvania to try to resolve” those demands, and “minimize costs and expense” while boosting payments to investors, Timothy A. Kolaya, the Florida lawyer who has been negotiating for the receivership, told Judge Ruiz during the hearing.

The receivers also hope to collect more money from Par borrowers. The largest Par debtor, Steven Odzer, whose prior bank fraud conviction was pardoned by President Donald Trump, had sued the receiver in a dispute over which side still owes the other how much.

Pauciulo was obliged to resign last year from Eckert, where he had headed the firm’s Financial Transactions Group, and was fined $125,000 by the federal Securities and Exchange Commission for his role in helping arrange the sale of “unregistered, fraudulent” Par-related securities from 2012 to 2020. He was also barred from practicing securities law in front of the SEC for at least five years.

Eckert is not the only big Philadelphia law firm drawn into the Par case. Brett Berman, a partner at Fox Rothschild, represented Par in its efforts to recover cash from hundreds of borrowers and sought to continue being paid for that service when the receivers took over in 2020; instead, the receivers fired the firm.

Berman has been identified by other lawyers in the case as “Attorney Number One” in the criminal fraud complaint by federal prosecutors earlier this year. According to prosecutors, the attorney was present as Par leaders plotted to lie to customers about their investments. Berman and Fox Rothschild were not named as defendants in that criminal case. Berman and Fox Rothschild have not responded to inquiries seeking comment.

The Eckert Seamans settlement depends in part on the receiver’s ability to win agreement from plaintiffs who have filed private lawsuits against the firm, citing damages from Par losses, that they blame on the law firm’s bad advice.

Resolving those complaints would “benefit the investors,” according to Judge Ruiz, adding that a settlement will “stop this bleeding” of litigation costs that will otherwise reduce the cash left for investors.

In particular, lawyers for the receiver told the judge they are hoping to settle with Vagnozzi. He agreed to pay $5 million to end the SEC’s civil complaint against him. He has since sued Eckert in Philadelphia Common Pleas Court, seeking $30 million. According to Vagnozzi, Pauciulo wrecked his business through bad advice by failing to warn Vagnozzi against the sale of unregistered securities, including Par, or to ensure his client warned investors of the risks, including LaForte’s criminal record.

According to George Bochetto, Vagnozzi’s lawyer, Pauciulo’s advice to Vagnozzi was “rogue, reckless, abominable,” and “completely unsupervised by anyone at Eckert. They allowed John Pauciulo to literally destroy hundreds and hundreds of lives. The Vagnozzis were chief among the victims.”

Bochetto called the $45 million settlement proposal between the receiver and Eckert “a very bad deal,” because it could leave tens of millions in “additional insurance coverage on the table,” and fails to review the “personal responsibility” of senior people at Eckert Seamans. Bochetto said the receivers were choosing the “expediency” of a faster settlement, instead of a longer fight that could enable Dean Vagnozzi to “put his life back together.”

Despite the threat of continued litigation, Kolaya said during the hearing that he hoped this summer to send each investor and anyone else with claims “an initial determination” about whether they have a valid claim and for how much. Claimants will be able to object to the finding if they disagree.

After that, “we can move forward to the claims distribution process,” Kolaya said. He declined to estimate the total number or value of claims, adding that the receiver is still trying to reconcile variances between Par’s own records and those provided by salespeople.