Bentley brothers take their 4,000-person Exton software firm public. It’s worth $8.7 billion.

Greg Bentley talks about how he and his brothers built Bentley into the biggest homegrown software company in the Philadelphia area, and why after 30 years they're finally filing for an IPO.

In a warm welcome from investors hungry for new tech stocks, shares of newly public Bentley Systems Inc., an Exton maker of software for construction and engineering industries, opened at $22 a share Wednesday, then shot up 50% to $33.49 in its first day of trading. That gave the family-run company a total value of $8.7 billion.

Bentley, with sales of $737 million (more than half in Europe and Asia) and profits of more than $100 million last year, is not your typical Silicon Valley start-up IPO. It now has 4,000 employees worldwide and built its products over decades, along with its customer base of construction giants and public utilities.

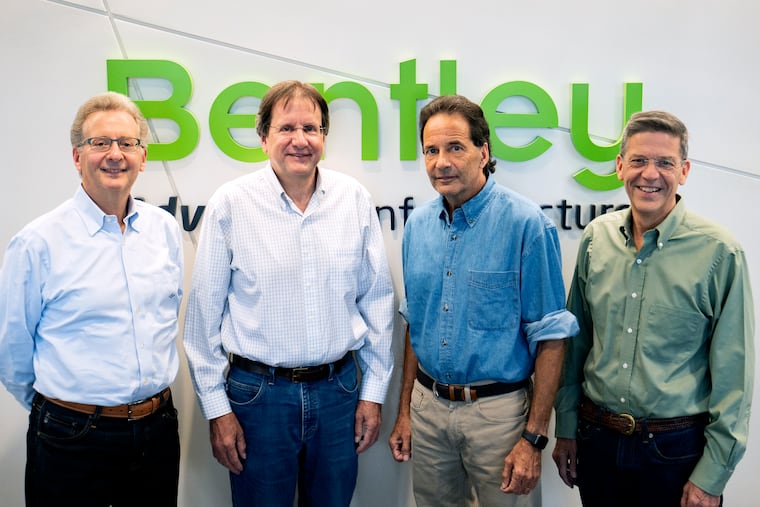

Founded in 1984, Bentley was built by a DuPont Co. engineer’s five sons, who shared Wilmington paper routes and jobs at Wassam’s Variety and attended the neighborhood public high school, John Dickinson.

They are chief executive Greg Bentley, the oldest brother, now 65; engineers and executive vice presidents Keith, Barry, and Raymond Bentley; and brother Scott. Scott left the company about a decade ago to head underwater-robot maker VideoRay LLC and beer-keg maker American Keg, both of Pottstown.

Scott Bentley and other former employees sold the shares that now trade on the Nasdaq market and kept the proceeds, minus a cut for Goldman Sachs and other investment bankers.

Those public shares are still just 4% of the company’s total, but that’s enough to establish a market price to value the shares given to Bentley employees to save for retirement, Greg Bentley said in an interview.

“That is the driver and the reason” for the IPO, he added. As a business, with voting control still firmly in Bentley’s hands, “we’re just going to keep doing what we are doing.”

Feeling similar pressures to reward veteran staff, other growing family-owned area companies such as W.L. Gore and Wawa have set up employee stock-ownership programs (ESOPs) to spread the wealth.

But Greg Bentley said he preferred the example of Pennsylvania software companies such as King of Prussia-based Vertex, which sold its shares to the public, rather than only to employees. That family-controlled firm, which makes business tax systems, held an IPO for a minority of its shares in July and is now worth more than $3 billion.

He added that Canonsburg, Pa., manufacturing-software maker Ansys, now worth $26 billion, also grew steadily while it was controlled by its founder, John Swanson, before later going public.

Bentley credited Amanda Westphal Radcliffe, the second-generation co-owner of Vertex, with giving “very good advice” on how to go public and allocate shares to staff while retaining voting control for the founding family.

Philadelphia was an early center of the computer industry — and Pennsylvania remains an attractive place to hire engineers and build computing businesses, Bentley says. But in contrast with hyped companies taken public even before they are profitable, the state’s family-owned tech firms tend to be “conservative, mature, cash-generating businesses” whose bosses are in a stronger position to name terms when they finally go public, he added.

Still, now that his firm has a multibillion market value, Bentley said he hopes the successful public offering gives positive exposure to the construction and utilities engineering and infrastructure firms that are his company’s markets.

“We’ve always been good at engineering,” he said. “We are doing better at marketing.”

Now that it is public, it is a first step toward Bentley becoming an acquisition target for rivals such as Autodesk, or multiproduct software giants such as Oracle, which in 2009 bought Primavera Systems, a Bala Cynwyd-based Bentley rival. Or will acquisitive SAP SE, which has its U.S. headquarters in Newtown Square, make a run?

Bentley has so far preferred to do the acquiring. For example, in 2011 the company bought New Orleans-based Engineering Dynamics Inc., an offshore-oil-platforms design company. And in 2015, it purchased Oregon-based E-on Software, which did animation work for the Minions and Hunger Games movies, to make Bentley software more user-friendly.

The next year, after Bentley called off an earlier plan for an IPO, the German medical equipment giant Siemens, whose U.S. unit has offices in Malvern, invested $130 million in the company, in part for a private ownership stake.

Some of the brothers’ children now work for the company. Will voting control eventually pass to them? “Nepotism is not a bad word here,” the CEO noted. But, he insisted, “we’re not engineering a dynasty” and “super-majority voting control will phase out over time.”

The company paid its owners a special $390 million dividend last month in advance of the sale, and also agreed to borrow up to $125 million from PNC and other banks.

“We face intense competition,” Bentley warned investors in its IPO filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.