Some guy had my bank account and driver’s license numbers. Would he get my money?

Identity theft has risen sharply during the pandemic. I experienced this because an imposter had scooped up a lot of my personal information and was now trying to breach my bank account.

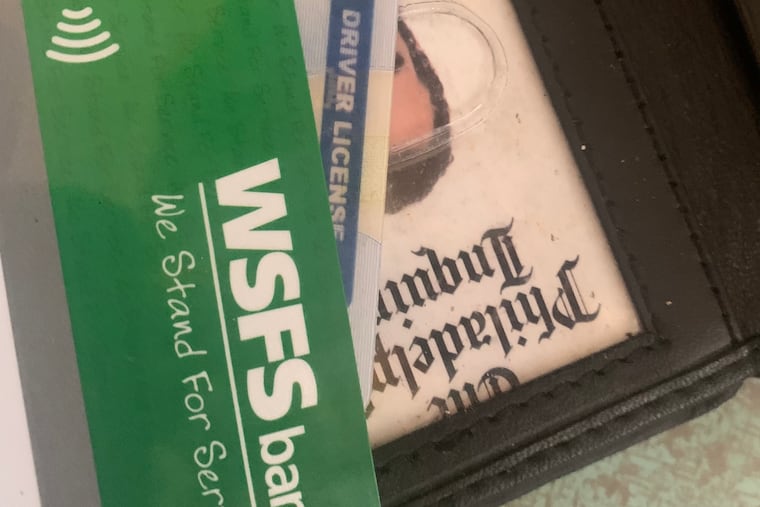

A couple of Thursdays ago this guy — call him Al — walks into a bank — a branch of my bank, WSFS, but out in Chester County, where I don’t live — and tells them to cash a fat check. From a real estate company. With my name on it.

Let’s see some ID, says the teller.

Al shows a driver’s license. In my name. With my date of birth. My address. Someone else’s license number. And a face that, well, you’d have to squint ... .

She asks his birthday. He gets the month right. But he’s off by eight days. From the license he just handed her.

The teller keeps that to herself. Can’t cash this, she says. Third-party check, not from our bank.

Ok, says Al. Deposit it, and I’ll just withdraw some cash. (From my account.)

He has the account number. And a credit card from another bank, with my name on it. Which turns out not to be active.

This will take a few minutes, she says.

Al leaves the line and shuffles back toward the lobby, to wait for my money, or for his nerves to give out. They usually wait a little, then head out the door, and aren’t seen again at that location, the teller tells me later.

She steps over to her coworker, the one born with an extra dose of personality. She speaks to him, quick and quiet.

The coworker steps to the door, turns, and stops to talk to Al, friendly-like. Soon it’s a conversation. They talk, and Al stays, a little longer than guys like him usually hang around, waiting for someone else’s money.

Meanwhile, the real me is hammering on my computer, yelling at my boss, on deadline, 30 miles away.

My other phone rings.

“Are you in the bank right now?” the teller asks.

What bank?

“Do you have a mustache?” she asks.

Not since, well, my last driver’s license photo.

“We’re calling security.”

I message my brothers, who live out that way. One, who has this history of confronting knuckleheads, writes right back: “Would you like me to drive over there and have a nice little chat? I can be there in 5.”

I leave the welcome-party for the East Whiteland Township Police, who get there soon enough. Like the bank staff, the officers quiz Al. He’d been “down on his luck,” he says. He’s had to sleep in a car. Someone approached him about visiting banks to cash checks, with corresponding ID, for a cut of the proceeds.

That’s criminal, sadly for Al. “He attempted to cash a check with your name listed as the payee,” as Officer Chris Stymiest told me. “When that was declined, he attempted to deposit it and withdraw the cash.”

It’s been happening a lot, the bankers told me, especially since the pandemic, and especially this year. Sometimes they hire addicts, one of them said.

Identity theft was up sharply during the pandemic. The Federal Trade Commission says bank fraud identity theft reports zoomed from about 5,000 a month in 2019, to more than 7,000 a month last year, and 10,000 a month this year, though they dropped a bit after peaking in March. The FBI cited the pandemic — with more of us working from home, from under-protected computers, along with whatever stimulus the shutdowns gave theft ring leaders. (Credit card ID fraud, which is about three times as common, showed similar trends.)

Delaware, where I live, and a banking center, was among the harder-hit states for ID fraud overall; Pennsylvania and New Jersey were also above average.

The scammers buy or steal IDs and account numbers. If there’s a picture, they try to find a person who maybe looks like it. A little.

With all this year’s stock-market-driven bank mergers and cost-cutting system upgrades, they figure the bankers are distracted. Especially right before closing time, which is when this happened.

Often they are right, and they get the cash, and the bank has to make it good. Especially, I guess, when the scammers happen to know, and remember, their purported birthdays.

Al, down on his luck and fuzzy about numbers, spent the night in jail. The judge set the bail low — $500. Someone came and posted it.

The police offered no insight on where Al, or his manager, got my financial information: it’s an active investigation. The bank froze our account. We got new cards and checks. We had to make new direct-payment arrangements with our employers, utilities, insurers and charities.

Officer Stymiest suggested we tell the credit bureaus our personal information was compromised so they can send us a special alert the next time someone says they’re me. And check our credit reports. The usual digital reset, when other people pretend they are you.

The officer said he didn’t expect Al would show for his hearing in the district courtroom last Friday. He didn’t. The judge signed a warrant. Which means things might go worse for Al, when he’s stopped again.

“We are proud of our team,” said Shari Kruzinski, the bank’s chief customer officer. She urged customers to check their accounts, a lot, and call fast when you see money vanish. Call TransUnion and the other credit bureaus, and the Social Security Administration if they got your number. File a police report. Maybe they’ll find a pattern and disrupt the thieves before they hit you again.

My bank is fortunate to have had these plucky staffers at that outpost, that day. They protected me better than all the digital codes and remote controls, the way this worked out. I hope they are paying them enough.

I can testify that East Whiteland Township is well-protected, as prosperous suburbs are, by a responsive police department. Even if the courts aren’t set up to hammer small-time scammers, or, more important, the larger thieves behind them.

Wherever he is out there, I pray that Al’s luck improves, to where he no longer feels his best chance of a payday is to pretend he’s me. Or you.