Vernon Hill’s control of Republic slipping away after boardroom rebels win in court

Federal Third Circuit judges overturn lower court decision that favored chairman Vernon Hill.

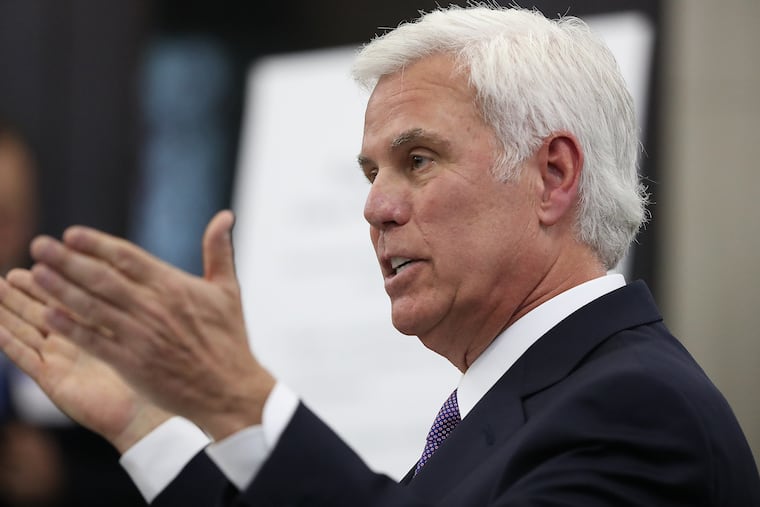

Vernon Hill appeared set to lose control of Republic Bank after an appeals court ruling Wednesday gave his rivals, including Hill’s predecessor Harry Madonna, control of the 33-branch, Philadelphia-based bank and its parent company, Republic First Bancorp.

The decision by a three-judge Third Circuit federal appeals court panel in Philadelphia overturned U.S. District Judge Paul Diamond’s actions, which had kept Hill in power as the CEO with the support of just two other directors on the seven-member board and called for an appointed custodian to set up elections that could settle a board fight between the two groups.

After the court ruling, anti-Hill directors moved to fill a vacancy on the board with an ally, investor Ben Duster. That would gave their group a 5-3 advantage over Hill and his remaining supporters, enabling them to act more freely.

In a statement, Hill and his two remaining board allies called the rush to add Duster “a shocking and unfortunate” move, adding that Duster has business ties to billionaire Wall Street investor Steven A. Cohen. Cohen invested in previous Hill companies, but in the Republic fight his longtime aide Andrew Cohen has allied to Madonna. A spokesman for the Madonna group had no immediate comment.

It was the latest step of a months-long fight that has so far enriched lawyers in Philadelphia, New York and elsewhere at shareholders’ expense.

After an investor-led call for spending cuts, higher profits and a possible sale of the Philadelphia-based bank, the board last spring was deadlocked, 4-4, between Hill and Madonna backers — until director Theodore Flocco, a Hill ally, died in May. Madonna and his three allies then used the one-vote majority that Flocco’s death gave them in an attempt to unseat Hill as the bank’s CEO, which Diamond blocked in favor of a custodian-managed process designed to let shareholders decide which faction should have a majority.

But the appeals court ruled that the Madonna group had acted rightly, and Diamond’s intervention went beyond what the law required. Appointing a custodian should be done “only in an extreme case,” according to the decision, written by Judge Kent Jordan, of the U.S. Court of Appeals. ”This is not such an extreme case,” he added, “though its facts are dramatic.”

Diamond’s action — “no doubt well-intended” — lacked “the required caution, circumspection, or justification for such a drastic step,” Jordan continued. In seizing control, Madonna’s group followed the bank’s own bylaws, he concluded: “They were and are entitled” to replace Flocco and grant themselves a clear board majority.

That would give the Madonna group the power to change leaders and direction, and to explore the sale of the bank.

Madonna supporters include Cooper Health chairman, insurance executive and Democratic Party leader George Norcross, a leader of a group that owns nearly 10% of the bank, along with Greg Braca, a former TD Bank executive and potential Hill replacement.

The Norcross and Braca group said in a statement that following the appeals court ruling that Hill should be placed on “administrative leave” as Republic auditors review contracts granted under his administration.

At his previous banks, Hill awarded work worth millions to his wife’s design firm and other family-related businesses as a means to expand rapidly and ensure quality control, even as those decisions attracted scrutiny from regulators and criticism from investors during periods when profits and share prices were down.

Hill’s innovations — including siting branches on highly visible corners, extending hours of operation, setting up rapid indoor and drive-up teller lines, and allowing pets in branches — were copied by larger banks in the 1990s after Hill’s Commerce Bank gained customers at their expense.

But critics say those features are of less value as customers shift to online banking. Indeed, Republic’s stock price languished, compared with other banks, under Hill’s management. Hill has lately proposed spending more on technology.

Hill, a Republican who backed successful politicians of both parties, and Norcross, with close connections in Trenton and Washington, were allies in the 1990s and early 2000s. Hill’s Commerce for a time handled Norcross’ municipal and corporate insurance business and Norcross served as Commerce’s vice chairman. They fell out over directors’ response to federal regulators’ probes of Hill’s banking practices in the mid-2000s.

Hill, of Moorestown, previously started and ran Commerce, which opened more than 400 branches in metro New York, Philadelphia and Washington from offices in Marlton, and MetroBank UK in England. He left both of those banks after coming under pressure from regulators. After Hill left, Commerce was sold to Braca’s former employer, Canada-based TD Bank, in 2007.