Steal money from the feds? First, meet Jeff Grant, an ex-con who committed loan fraud

Thinking of using your SBA loan money the wrong way? Jeff Grant has a cautionary tale.

Thinking about stealing the government loan money you received in pandemic help?

Before you do, listen to Jeff Grant’s story.

After his opioid addiction, his theft of U.S. loan funds, and a federal prison sentence, Grant’s life as a lawyer and business professional was over.

But according to him, his new life was just beginning. And for small business owners feeling desperate — enough to steal — he’s created a safe place to talk anonymously and seek guidance.

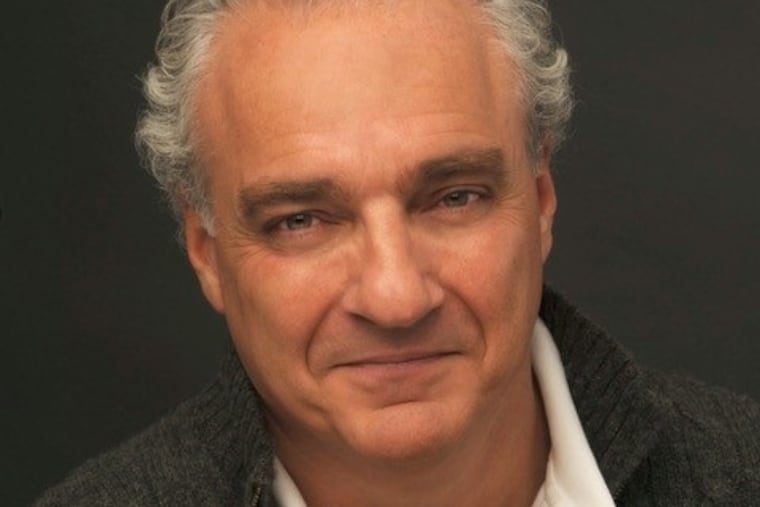

Now clean and sober, remarried and out of prison, Jeff Grant, 64, co-founded Progressive Prison Ministries, what could be America’s first support group serving the white collar community —- in particular, those who committed white collar crimes and may have served prison time.

Based online, the group attracts many business owners and white-collar workers from Philadelphia.

“Philadelphia has the second largest concentration of our support group members,” Grant said, including Seth Williams, former Philadelphia district attorney, who Grant says attends regularly. Williams was released from prison earlier this year after serving time for his 2017 bribery conviction.

Grant was convicted after fraudulently obtaining $247,000 in federal aid soon the Sept. 11, 2001 attacks, falsely claiming to have had a law office in lower Manhattan that had been shuttered by the disaster. He used the money to pay down personal credit cards. Meanwhile, his pain medication addiction ramped up, as did his marital problems.

“In 2002, I resigned my law license and started on the road to recovery. But it all caught up with me about two years later, when I was arrested” for misrepresenting information on his loan application. He served almost 14 months at a federal prison for wire fraud and money laundering.

“So much of my story is tied to my wife, Lynn Springer," he said. They met in drug addiction recovery in Greenwich, Conn., and have been married for 11 years.

"I was a very bad bet, but she stayed with me through prison and the rough years after,” said Grant, based in Woodbury, Conn. He celebrated 18 years clean and sober on Aug. 10.

Basing it on a 12-step program, Grant created his support group for white collar criminals and their families after earning a divinity degree from Union Theological Seminary in New York. He now hosts an online White Collar Support Group every Monday.

“Here’s what business owners should consider when they take out disaster loans. Certainly, the majority of people requesting these loans are honest and upstanding entrepreneurs who have immense need for the aid, and will use the funds properly," he said. “That said, history has shown us again and again that when people are in dire need, they’re more prone to make impulsive, ill-advised decisions."

"My hope is that sharing my experience will help others avoid the consequences I faced.”

Sometimes referred to in the business press as a "minister to hedge funders,” he uses his experience to guide families and professionals in their relationships, careers and businesses, and to help them to stop making the bad decisions that resulted in loss, suffering and shame.

Rampant SBA loan fraud today gives Grant’s story new relevance. Wells Fargo this week said it fired at least 100 bank employees for improperly receiving coronavirus relief funds, and JPMorgan Chase & Co. also found more than 500 employees tapped the SBA’s disaster-loan program.

“What’s happening now is almost indescribable,” he said. “Nineteen years after committing my crime of SBA loan fraud, I’m now sought out both because of my cautionary tale and as a SBA loan fraud expert. Believe me, nobody was interested in the nuances of how bad things could happen in taking out disaster loans until COVID presented us with another huge disaster.”

Most recently, he hosted a podcast and interview with New Jersey politician Bill Baroni, who was imprisoned after the “Bridgegate” scandal with New Jersey governor Chris Christie, and had his felony conviction for corruption overturned by the U.S. Supreme Court.

Grant’s white collar support group includes mostly executives, lawyers, and other professionals, and — yes, they are mostly white.

He has held over 200 online support group meetings and averages about 25 attendees at each meeting: https://prisonist.org/white-collar-support-group/.

Weekly meetings require registration ahead of time for privacy, and only first names are used. On Grant’s podcasts, all guests are post-sentencing or back from prison.

“How’d my life get there?” Baroni told Grant on a recent podcast. “I’d been a practicing lawyer, teaching constitutional law and voting rights, I ran for the legislature in 2003."

“People have to make those tough decisions," he said. "I wanted to get [his prison sentence] over with. When you go through this, all’s changed, changed utterly,” Baroni said.

When Christie was elected governor in 2009. Baroni ran the Port Authority overseeing all six airports in the New York-New Jersey area, the bridges and tunnels, the PATH train system, two bus terminals and the entire World Trade Center complex. Baroni served just under three months of an 18-month sentence, but was released after the Supreme Court agreed to hear his case.

Other guests aren’t as famous, but just as human.

For the episode “When Mom Goes to Prison,” Grant hosted a woman prosecuted for white-collar crimes.

Jacqueline Polverari, convicted in 2014 of mortgage fraud, and her two daughters Maria and Alexa contributed an intimate look inside how crime and prison ravage families, and the steps needed to heal and put families back together.

“I used mortgage funds to supplement my business,” Polverari told listeners. “My kids were in middle and high school. I knew I was being investigated by the FBI and I hadn’t told the kids. I was guilty, knew I was going to jail, so I sat the kids down and told them the truth."

Her children didn’t comprehend the extent of her crimes. Jacqueline wasn’t sentenced for several years and her temper flared regularly.

“It was a long, drawn-out process. It started when i was a freshman in high school and didn’t end until she came home from jail my senior year of college,” Alexa said on the podcast. “She didn’t keep us in the dark. She told us the honest truth. That made it a little bit easier.”