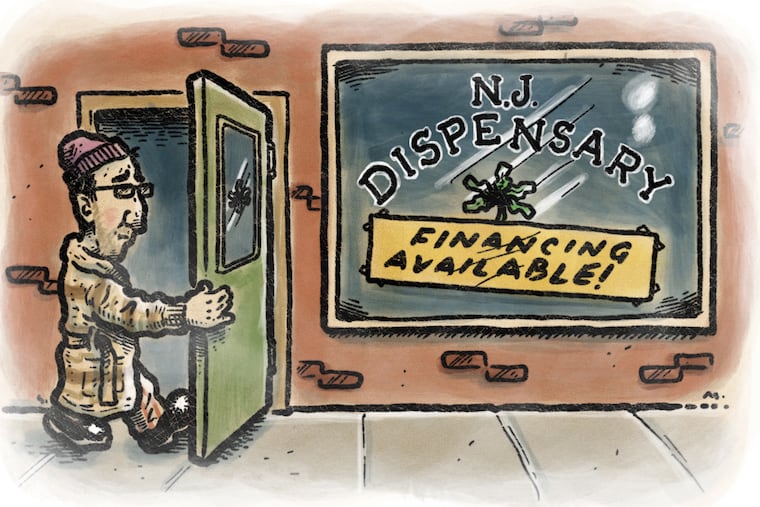

New Jersey has had legal weed for a year. It’s among the most expensive in the nation.

While prices typically drop as a market matures, for now, people in NJ are paying high prices for legal cannabis.

With one year of legalization under its belt, New Jersey has some of the most expensive recreational cannabis in the country. And it’s going to take time — years, likely — before that changes.

Prices vary, but many eighth-ounces — that’s 3.5 grams — of legally purchased pot in New Jersey go for about $60 before taxes. That’s about $17 a gram, with few discounts for purchasing larger amounts. An ounce runs about $455.

“That’s significantly higher than other recreational markets around the country,” Jeff Brown, executive director of the New Jersey Cannabis Regulatory Commission (CRC), said earlier this year. Prices typically drop as a market matures, and New Jersey’s fell by about 8% between August and February, cannabis market research firm BDSA said. But for now, Brown isn’t wrong.

Maine, by contrast, charged an average of $8.04 for one gram of legal marijuana in March, according to the state’s Office of Cannabis Policy. And in Oregon, a gram was selling for as little as $4, according to a February report from the state’s Liquor and Cannabis Commission.

So what gives in the Garden State?

High demand, low supply

In short, there’s not enough weed, or people who grow it, said Todd Johnson, executive director of the New Jersey Cannabis Trade Association (NJCTA). The association represents a majority of cultivators and dispensaries in New Jersey.

“Each state is essentially its own market impacted by its own supply-demand dynamics,” Johnson said.

And New Jersey is seriously lacking on the supply side. That’s not out of the ordinary for marijuana markets as young as New Jersey’s.

The state has 17 operating cultivators who grow marijuana, 11 of which grow recreational weed, according to the CRC, the fewest operational facilities among 15 states that the commission analyzed. In total, those cultivators have a “canopy” — the amount of space dedicated to flowering marijuana plants — of 418,000 square feet. That’s “far below the average of other states with legal cannabis,” CRC Commissioner Maria Del Cid-Kosso said in February.

» READ MORE: Everything you need to know about weed in Pennsylvania and New Jersey

Del Cid-Kosso added that the state has just one cultivation license for every 197,000 residents — far below the national average of one license for every 31,000 residents. Previously, the state capped the number of cultivation licenses at 37, a limitation it removed in February.

“Imagine if there was one lettuce producer for every 120,000 residents,” said DeVaughn Ward, senior legislative council for the Marijuana Policy Project (MPP). “It would make the price of lettuce pretty high.”

As of last month, an additional 25 cultivators with annual licenses were preparing to become operational. But it could take a year or two before enough cultivators are able to reduce prices because building a growing facility is expensive and time-consuming, Johnson said. After that, the price of some eighths of marijuana may drop to $40 or so.

But New Jersey will still be behind other legal states. According to the CRC, the average recreational-use state has 889 cultivator licenses, so New Jersey will need “nearly 850 more” to catch up. Chris Goldstein, regional organizer for the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, puts the number of growers needed much higher than that.

“New Jersey needs thousands of cannabis growers, literally,” he said. “That’s the difference. In other states, there are thousands. That’s what’s missing here.”

The ‘corporate cartel’

Goldstein takes issue with not only the number of cultivators the state has, but also who is doing the growing. New Jersey’s marijuana market is dominated by large, multistate operators such as Curaleaf that sell and grow around the country, with little participation coming from independents. That, Goldstein says, allows a “corporate cartel” to offer the same products it sells in other states at a higher price in New Jersey.

“It shouldn’t matter what state you’re in. Producing cannabis is a standard process,” Goldstein said.

To Ward, though, it’s more complicated, as each state has different tax structures, laws, canopy sizes, and numbers of producers . Plus, marijuana remains illegal at the federal level. So, unlike with alcohol, cultivators can’t grow their product in a state where it’s cheaper to produce, and then transport it to another state to sell, or just bring in more weed from outside the state to increase supply.

Even once New Jersey’s market can mass produce, there will still be $60 eighths. That’s true in almost every legal state, but the difference is quality, Johnson said.

‘Everyone wants to be champagne’

As more operators bring marijuana to market, we’ll see a “stratification” of brands, with high-quality marijuana remaining at a high price, and lower-quality cannabis going for a lower price. Sort of like Budweiser vs. champagne — an element that is currently missing from New Jersey’s market.

“In New Jersey, $60 is the only price point,” Goldstein said. “Everyone wants to be champagne, no one wants to be Budweiser.”

» READ MORE: It’s the one-year anniversary of recreational pot sales in N.J. Here’s how to find your closest pot shop.

The number of recreational dispensaries is also limited, with about two dozen in the state. The CRC has contended that additional locations and greater competition would help lower prices. But, the NJCTA’s Johnson said, having more retailers isn’t likely to make weed cheaper — just more convenient.

And, Johnson said, additional dispensaries would still be selling products they get from the state’s limited number of cultivators, which sell them to different retailers for similar prices. As a result, “prices will usually end up somewhere very close to each other.”

Ultimately, though, new markets such as New Jersey’s tend to see high prices early on. Massachusetts, for example, started sales in 2018 at $14.09 a gram, state records show. And Maine launched in 2020 at $15.83 a gram. Now, both states are far below their initial prices, which is a common trend for mature marijuana markets, Ward said.

Part of that, Johnson said, is that markets are able to balance their supply and demand over time. That’s difficult to do when a market such as New Jersey begins due to the sheer number of consumers who are “injected into the legal marketplace” at once. New Jersey, he estimates, has 650,000 to 670,000 of-age cannabis consumers — a group that dwarfs its medical marijuana program, which topped out at about 129,000 people in May, CRC records show.

“That is why the demand side of the supply-demand equation really shoots up,” Johnson said. “When you have low supply and high demand, you have high prices.”

How cheap is too cheap?

The issue, however, is that sometimes supply can far outweigh demand, and lead to a crash in the market, such as in Colorado, California, Oregon, and elsewhere, Johnson said. In those states, marijuana has become extremely cheap, which is great for consumers, but some operators are finding it difficult to stay in business.

“If you go too far with it, you have a complete oversupply, and some folks are going to lose their shirts,” MPP’s Ward said. “It really is trying to find that equilibrium.”

Goldstein doesn’t see it that way.

“I call that a correction,” he said. “That is what needs to happen in New Jersey — we would like a correction. We would like it to come back down to earth.”