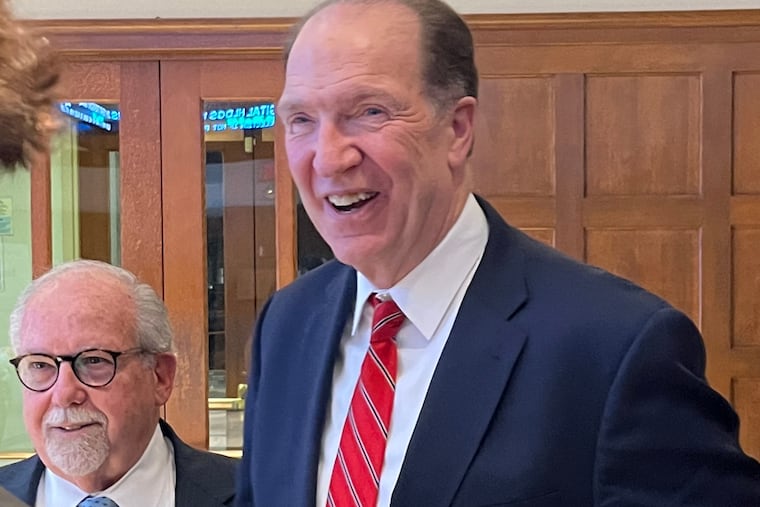

Ex-World Bank chief David Malpass warns global slowdown threatens unrest

Investment in poor countries will help stabilize world conflict, Malpass told the audience at St. Joseph's University during an event sponsored by the World Affairs Council of Philadelphia

David Malpass, who headed the World Bank from 2019 until June, knows his way around Philadelphia from his years as an investment salesman, long before he rose to top economist at the former Bear Stearns investment bank, or his service as a top aide to three Republican presidents.

He was back in town Tuesday, visiting at least one locally based billionaire investor (neither he nor the investor wanted to talk about it), and speaking to a full house at St. Joseph’s Haub School of Business for the World Affairs Council of Philadelphia. And he sat briefly with The Inquirer for questions.

The conversation has been edited for space and clarity.

China, Russia, and other countries are again ruled by strongmen. American leaders used to argue our way’s better, so we’ll win. But we aren’t hearing that lately. Have we lost confidence?

I really think the leaders in Washington have been taking the wrong approach, trying to scare people into fearing Russia and China because they threaten us. We should have attacked the Ukraine invasion as bad for the Russian people, and the same with [repressive Communist Party rule in] China, it threatens their progress. There are many people who would take encouragement from that approach.

The wars in Ukraine and Gaza dominate world news. Where else do you think people should pay attention?

My main theme is that growth is slowing worldwide, and it looks like that will persist. It’s worse in poorer countries because most investment gets faster returns in developed countries, so with slow growth, there is less available for infrastructure and industry in the rest of the world. There is only so much sweat equity that poor countries can produce by working hard for themselves.

The slowdown, the lack of investment, contributes to instability. Not just in places like Jordan, where I just visited, but also in China, where workers are again having to look abroad for opportunity.

We are like most of the countries in the world: We think mostly about conditions here, including the economy. We are in a period of historic expansion of U.S. government spending. I complain about the size of the budget deficit and the national debt and the Federal Reserve using financial assets to buy bonds, which takes capital from other uses around the globe. Markets should be able to allocate capital, not just governments.

Are other countries doing a better job than the U.S. at managing spending?

Historically Germany has had a sense of fiscal responsibility. But there are growing countries that take these concerns seriously. Brazil has really pulled down its deficit. Mexico has seen the positive impacts of its own fiscal improvement.

China now has some of the same problems we associate with Japan — deep debt and a population that is starting to decline. But China is so much larger than Japan that it probably has more staying power in its interactions in the rest of the world. They are still deeply and thoroughly engaged in global industrial supply chains.

Is China losing its industrial dominance?

We are seeing new [factory] investment in Mexico and Vietnam. But China is making some of those investments in resources and in manufacturing, as its economy continues to mature.

China is run by a one-party system based on a central plan that includes a very vigorous industrial policy. What is the best way for the U.S. to compete with that? Clearly we are still stronger with innovation. That shows up in everything from semiconductor design to financial services. Our leadership is still apparent. But we can never rest on our laurels.

China is competing directly with the U.S. They have the big lead in materials science, in refining [electric battery components]. And they still have economies of scale for products such as solar panels.

Most important, they are producing many more engineers. The U.S. has to play rapid catch-up in terms of education — in science, math, and engineering.

The U.S. birthrate is collapsing, too. Do we need more immigrants?

We have to find a way to allow skilled people to stay in the U.S. Our current system is not functioning well. The H-1B visa program faces a lot of difficulties. We need better ways to find talented people.

Why aren’t America’s major political parties stressing these issues?

The U.S. is very inward-focused. The media focus on crime and the border. And the political candidates themselves have gone into personalizing the issues in their attacks.

We have to recognize U.S. leadership is vital in the world. We need to project that and do more to refine our global institutions. They have deep flaws, and the U.S. needs to find them pathways that serve our national interest.

What are the people who come to your talks asking about?

Refugees and how to make aid [to nations] effective. Debt and the role of regulators like the Fed. And the importance of matching climate change spending to actual benefits consistent with development. Not just make ambitious promises. This is the core of our 2021-2025 World Bank Climate Action Plan.