New car, no perks: As chip shortage persists, more car dealers are selling vehicles without bells and whistles

As shortages persist, more auto dealers are selling vehicles without the bells and whistles.

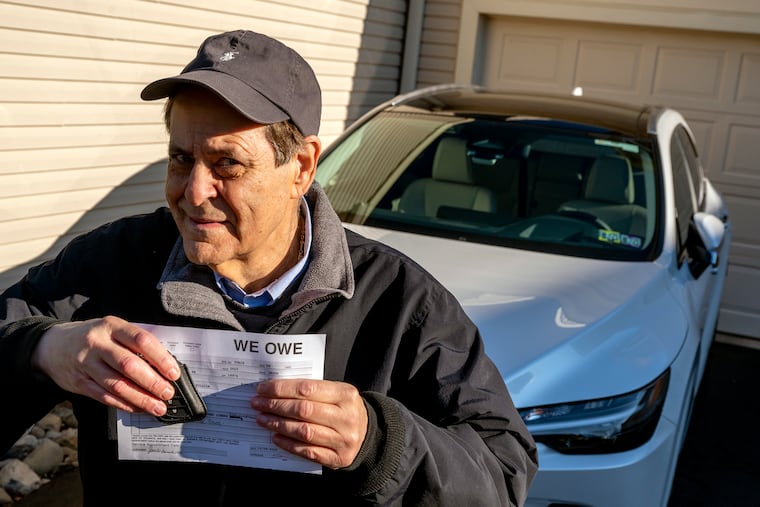

Joel Mickelberg of Warminster was coming to the end of the lease on his 2020 Lexus RX350, so he returned to the dealer where he leased his two previous Lexuses, Thompson Lexus of Doylestown.

He decided to go hybrid with a 2023 Lexus RX350h, but was surprised when he picked up his vehicle in December: The car came with only one key fob. That might seem to be a minor inconvenience, but so many automatic features are tied in to user profiles, which are loaded with the key.

“You would think that they would move heaven and earth to not deliver vehicles with only one key,” Mickelberg said.

Lexuses with just one key fob. A Chevrolet Silverado missing rear seat heaters, parking assist, and wheelhouse liners. A Mini Clubman without a heated steering wheel. A Buick Enclave without parking assistance technology. BMWs without lumbar support or touchscreen functions.

While the U.S. auto industry struggled to supply vehicles amid rising demand during the pandemic, one way automakers were able to fulfill orders was by leaving off some nonessential components.

Finding real information on how many vehicles were built like this is difficult. No independent firm tracks the data, and automakers don’t really advertise it, but it exists in showrooms and on window stickers everywhere. Delete: Heated seats. Delete: Electric tailgate.

Expectations vs. reality for chips

A chip in your vehicle has to be very reliable and proven because it’s called upon to work in weather extremes, explains auto analyst Sam Fiorani, vice president of global vehicle forecasting with Automotive Forecast Solutions in Chester Springs.

Chips first made their way into automobiles after the 1970s gasoline crisis, according to a Forbes essay by Willy Shih, a professor at Harvard Business School and co-author of the book Producing Prosperity: Why America Needs a Manufacturing Renaissance.

Also known as semiconductors, chips now make up such things as the body control module, controlling such systems as power windows, door locks, and side-view mirrors, superseding the mechanical components that commonly ran those systems. If those systems weren’t unreliable to begin with, they became so over time.

“The auto industry sees itself as the most important part of their suppliers’ business,” Fiorani said.

But the tried-and-true chips used in vehicles are less profitable than the newer versions that power cell phones, computers, and video games consoles, Fiorani said — things that consumers were actually snatching up in great numbers in pre-vaccine days, when everyone was stuck at home and no one was driving anywhere.

At the beginning of the pandemic, when the number of car sales plunged, the auto industry exited the queue for computer chips, assuming that they’d be top priority when they needed supplies.

But that’s not how it played out. Instead, when automakers were ready to resume building vehicles, they found themselves at the back of the line, which led to the chip shortage we’re still experiencing today.

“When it came to semiconductors, they found they are not the most important out there — the industry is just not used to that,” Fiorani said.

Retrofitting frustration

Whether the shortage of options affects sales has been hard to say, as automakers still could not keep up with demand. New car sales are down to about 13.7 million for 2022 vs. just under 15 million in 2021, mainly on production snags.

But surely many buyers seeing luxury cars such as Mercedes with cranks and manual pulls for their seats or Audis that needed a key put into the ignition instead of push-button starters were unimpressed.

And though he’s not shopping luxury brands, count Michael Abrams among them.

The 44-year-old from Ambler has a lease on a 2020 Mazda CX-5 and his wife, Jenna, has one on a 2021 Volkswagen Atlas. They visited dealers recently to see about replacing their vehicles but they’ve decided to extend their leases, and they’ll probably just buy the vehicles outright when the extension is up.

“None of the Mazdas on the lot have electronic tailgates because they have no chips,” Abrams said. “The VW dealership had zero SELs on the lot that had power tailgates.”

Sure, a later retrofit is promised, or a credit is offered. But it’s a frustrating situation for everyone.

Still, many consumers have just forged ahead and bought new vehicles anyway.

Among those buyers is Jeanine Amann of Honey Brook. She’s the owner of a 2022 Toyota Highlander SUV that lacks many of the features she wished it had: no memory seats, heated seats, or even leather seats. But the 2012 Mazda CX-9 she owned with her husband had blown its engine early last year, and the couple were stuck, so they bought the only Highlander on the lot, in black.

“Having fabric seats with two kids and three dogs is not ideal,” said Amann, who with her husband, Jonathan, owns Amani’s BYOB in Downingtown. “Of course we do have stains and smells and stuff like that.”

Buyers such as Amann are probably more common than experts and auto industry leaders had expected, said Joseph Yoon, consumer insights analyst for the everything-automotive site Edmunds.com. Many people thought buyers wouldn’t settle for cars without a lot of the extras.

“I think the opposite was true, and people didn’t care,” Yoon said. “They were, like, hey, I need the car right now.”

And yet consumers who are holding out for the right options have their own issues to face.

Joe Velten of Warminster put his money down in November on a 2023 Honda HR-V. And now, in April, he’s still driving his 2015 GMC Terrain with 90,000 miles on the odometer.

The 79-year-old retiree wants the HR-V EX-L, top of the line, with heated seats, in his color choice, Nordic Forest Pearl. (After teaching English at Archbishop Wood for 52 years, and still volunteering there now, he’s earned it.)

“The frustrating thing to me is, obviously, the dealers want to sell what they have, but there’s no actual way to order a car,” Velten said. “I can go to a furniture store and order a specific piece of furniture, in terms of the color and the style that I want.”

Relief ahead?

Automakers are looking to the second quarter of 2023 for some relief.

“In terms of overall supply chain shortages, our plants continue to face intermittent production delays due to many supply chain disruptions, and we anticipate challenges into Q1 of 2023,” Leigh Anne Sessions, senior manager for Lexus Communications, said in an email before earnings were released earlier this month.

Fitting into Sessions’ expectations, Mickelberg confirms the second key fob for his Lexus is expected to come in the second quarter. He already received his all-weather floor mats in January, another item that was left off the RX350h.

And the outlook remains challenging for brands across the spectrum. Among the most affected vehicles, according to Auto Forecast Solutions data, is the Honda Civic, estimated to have lost more than 40,000 units in 2022. That means the company built 40,000 fewer Civics than it had planned because of chip shortages.

The Chevrolet Equinox, Sierra, and Silverado are expected to be hit hard in 2023, with more than 100,000 vehicles planned that likely won’t be built. The Ford Edge and the F-Series, as well, although the numbers could change if semiconductor production comes back in time, Fiorani said.

But Fiorani thinks the real solution lies further in the future — when the Chips and Science Act signed into law in August begins to boost onshore microprocessor manufacturing. He said it’s the key to getting chips up to the speed of vehicle production.

But it won’t be an overnight solution, as factories must be built and workers trained.

“These things take time, and a lot of money,” Fiorani said.