Eric Zillmer, contender for Most Interesting Man in the World, leaving Drexel AD post | Mike Jensen

Zillmer was not commuting in from some distant planet. He just seemed to notice all the planets and the stars past them while he was working at his day job.

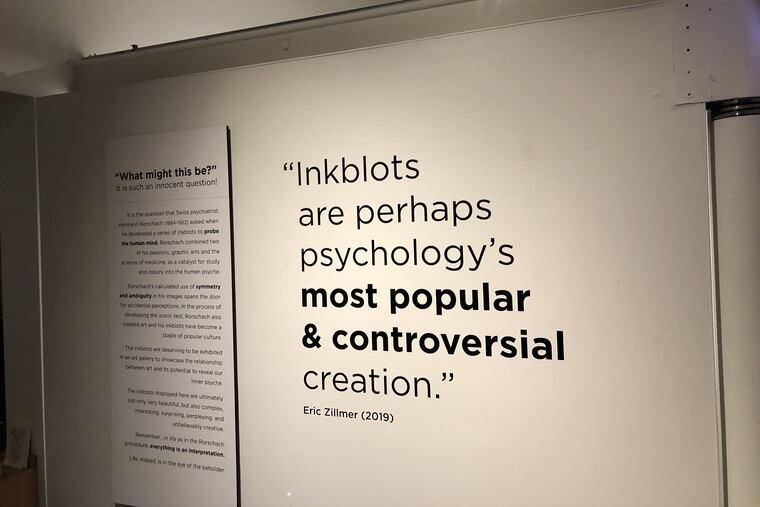

This was December of 2019, on Drexel’s campus, a block from Market Street. A talk with Drexel athletic director Eric Zillmer, just not in his office — walking around a gallery where Zillmer, also a tenured Drexel neuropsychology professor, had curated with his own daughter an exhibit on the art and science of Rorschach inkblots.

The Most Interesting Man in the World, they’d call him around the office — athletic director division, anyway.

The interesting part won’t change when Zillmer stops being Drexel’s athletic director at the end of the academic year, after a 22-year run. A typical Zillmer conversation included some search for higher ground. It didn’t take much goading.

» READ MORE: Drexel athletic director Eric Zillmer stepping down after 22 years

“What makes sports drive?” Zillmer said that day walking around the gallery. “You talk to a sports administrator, they go, it’s a business. You slice it, you dice it, you sell it. … Every organized civilization has invested in organized sports. There’s something much deeper.”

It’s hard to get to that, Zillmer added. “Otherwise you would live there.”

Yep, always enjoyed talking to Zillmer. Drexel fans might have been driven batty by this stuff, and by Zillmer’s devoting to Drexel being a national squash hotbed. Plenty of Dragons fans were more than ready for this news … Fine. That’s sports, too. Zillmer was not commuting in from some distant planet. He just seemed to notice all the planets and the stars past them while he was working at his day job.

“Then this idea of a flawed hero ...” Zillmer said, stopping by some inkblots.

Zillmer was as competitive as the next AD. When the Big 5, always boxing Drexel out, wanted to give the Dragons some kind of “nice job, guys” award at their annual banquet, Zillmer finally told his coaches to stay away. Sure, he worked to provide a home to squash’s governing body and saw real gender equity in providing the same number of rowing scholarships, men and women. But he knew hoops was Drexel’s bread-and-butter, what he’s to be judged on, pro and con, seats full or not.

This one paragraph of Zillmer’s athletic department biography covers a lot of terrain: “Born in Tokyo, Japan, and raised in Europe, Dr. Zillmer is bilingual in English and German. He has a passion for art and has exhibited work as part of Manifesta7 in Trento, Italy and with Yoko Ono in Philadelphia. He studies the classical guitar and is a frequent producer and participant of Guitar Salons. He enjoys golf, tennis, court tennis, and squash and riding his Harley and Vespa. Dr. Zillmer comes from a sports-oriented family; his father played baseball for Army ’44, and his mother coached his sister on the Olympic team in figure skating (Grenoble, France 1968).”

No, he couldn’t have been an AD in the Power 5. Zillmer saw all along that was a different game. He’d call them out on their hypocrisy, straddling the line between being part of a system that he didn’t quite trust.

Some Zillmer work had little or nothing to do with sports. He wrote a book on murderers. He wrote one on the personality of Nazis, looking at genocide. He coauthored another on the art and science of those inkblots. He has studied terrorism. Most of his work trying to understand sexual predators was in the 1980s.

Back to the gallery, looking at the inkblots …

“Somebody who makes mistakes, rises from the ashes, succeeds,” Zillmer said of why sports is a vehicle for cheering flawed heroes. “Why is that important? Because we’re looking at ourselves. Sports is really a reflection of us. … It’s so beautiful because you can lose or win, which means nothing, but actually we trick ourselves that it means everything.”

Hence, the dramatic symbolism, Zillmer said, “sudden death” and such.

“Even a fan, technically, is a religious worshiper," Zillmer said that day. “That’s how you have to think of them, because they’re not objective observers. It’s truly spiritual.”

Zillmer brought up the Palestra — “it’s a cathedral of basketball, it’s not an arena. It looks like a Quaker Meetinghouse.”

What is different in sports from art — “the moment matters,” Zillmer said. “In music, too. … This minute-by-minute, second-by-second way of living is so beautiful, you can live in that moment. In fact, we manage the moment now. You can stop the clock. Delay it. Let’s review it, put more time on it. That’s the best, if only I could put more time on my life.”

Being No. 6 when Philadelphia college basketball is identified by the Big 5 …

“You’re an outsider, you’re not a member of the community — it hurts,” Zillmer said. “But I respect the Big 5. I understand that it meant something, especially in the ’50s and ’60s, and ’70s. Doubleheaders. The streamers. So it created a meaningful cult of basketball. It made Philadelphia the best basketball city in the country.”

He respects it but knows he’s not part of it, Zillmer said. “So you have to be different, OK? I’m an Army brat so I don’t actually have a home. … I think we’ve made a place at Drexel, we are part of the city.”

Everything doesn’t have to lead to some deep meaning, Zillmer added. A dunk or pick-and-roll doesn’t have to explain the birth of your child. But this talk does seem to explain Zillmer’s next sports venture at Drexel. If he thinks new eyes will be healthy for the athletic department, who’s to argue? After a one-year sabbatical, Zillmer plans to develop a Drexel Global Sports Leadership Lab.

A think tank run by a man who doesn’t need a tank to start thinking. Your view of Zillmer? Kind of an inkblot test.