Penn basketball legend Jerome Allen wrote a tell-all book ... about himself | Mike Jensen

In "When the Alphabet Comes," Allen tells his story not as a hero or a victim, but rather as a person asking and answering the tough questions about his life.

So Jerome Allen wrote a book.

It’s a remarkable book. Some accomplished filmmaker should give it a read, maybe try to film this tale. This is Allen’s story — he’s the protagonist of When the Alphabet Comes — but he does not go easy on the protagonist.

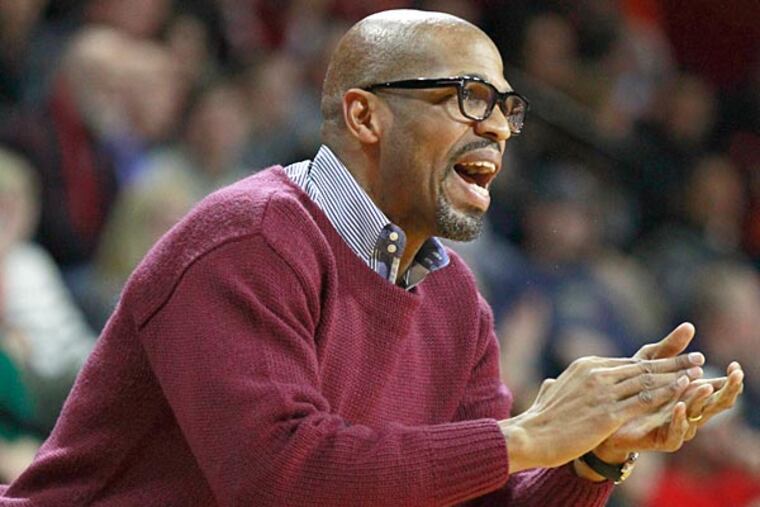

You may already know about Allen’s ultimately unsuccessful tenure as head coach of his alma mater, after he had been one of the most important Penn Quakers basketball players in history. You’ve since learned how Allen let his school down with actions that earned him the title of convicted felon, and resulted in what nearly amounts to a lifetime ban from NCAA coaching. His own cousin, he reveals, called him a rat.

If you also wondered how Allen didn’t lose his job as a Boston Celtics assistant, which he has today, there are clues to that, too. Why this man remains a respected figure in his sport, long revered by many of his peers.

Allen did not point out that part himself. He did not try to tip the scales too far in his own favor. He did mention seeing Kobe Bryant after Bryant’s last game as a Laker against the Celtics, how he was thrilled to still be recognized by Kobe. Allen took his children to see Kobe in the locker room. “He was telling them stories about me in my younger days. Can you imagine? Kobe … sitting there telling your own kids that he stole from their dad’s game? It blew my mind.”

From the outside, there was little surprise in that. Allen was that skilled, moving from Episcopal Academy to Penn. But his stories about growing up in “Norf Philly” and then Germantown, center the text in the reality of his life, why anytime he heard a reference to “25 percent,” it struck deep, since he had three close friends growing up. One was stabbed to death inside a car when he was 17 years old, one died of an overdose at age 23, one ended up a homeless crack addict. “And then there’s me.”

DeAndre, the friend who was stabbed to death, changed the arc of Allen’s life, he wrote, by taking him to the Gustine Lake Recreation Center. Allen got noticed in there, he wrote, not just on the court, but doing his homework in the director’s office. “I was only in that office doing homework that one time. All the other times I was in the Director’s office, I was trying to steal sodas, ping pong balls, anything I could get my hands on.” That one time was it, though. Bob Johnston and Tennis Young called James Flint (Bruiser’s father), and he called Dan Dougherty, the coach at Episcopal Academy.

“My exposure to access and privilege was a complete contrast to my home life,” Allen wrote. “At home we were appreciative for bare essentials — you know, milk for the cereal, and hot water for baths.”

Allen wrote about one time when the hot water bill wasn’t paid, so he was boiling some, keeping it from his sister, mistakenly stepping in the boiling pot of water. He’s not the hero of the scene.

The book explains how years later Allen “developed a disdain for the privileged,” when he was Penn’s head coach, how he recruited some privileged kids, but some were using this to get into the Ivy League school, eventually leaving basketball behind. “One of my college teammates came from an affluent family, and he was a beast,” Allen wrote, noting this teammate was an important part of three Ivy titles. He couldn’t completely set aside that demographic, he told himself. “Then it happened again.”

Allen said he was ultimately lucky that he was no longer Penn’s coach when the FBI came calling. He’s dead-on there. The scandal would have been exponentially bigger, after Allen ultimately testified last year in a federal fraud trial of a Florida health-care executive, how he had taken roughly $300,000 in bribes to get the man’s son into Penn using a basketball priority slot.

This all was a precursor to the unrelated Varsity Blues scandal, where all sorts of children of privilege got into prestigious colleges, from Stanford to Yale, using sports admissions slots. Some had never even played the sport in question.

Playing the role of victim, hero and villain isn’t easy. … ultimately led to me identifying the sins of my own heart.

“I wrote my story from three different vantage points,” Allen wrote toward the end. “Playing the role of victim, hero and villain isn’t easy. … ultimately led to me identifying the sins of my own heart.”

The hero part wasn’t as a basketball hero, despite Allen playing in the NBA and being a professional star overseas. For those close to him, Allen always was known as a caring individual. (“I gave sometimes so that others wouldn’t think I forgot where I came from.”) It made his fall all the harder to fathom. Yes, money was tight. His own children have been extraordinarily successful. That plays into his story in different ways, in his desire to provide, and the most profound pain of his fall.

“My jealous heart brought to the forefront that having the access and privilege associated with a relationship with God should be my ultimate priority,” Allen wrote, and a scene on a street in Memphis would be another scene in a film of his story, an encounter with a homeless man, the man ultimately saying, “Hey, you gotta have faith — pray and have faith.”

“How did he know I was angry, confused, sad, guilt-ridden, and depressed?” Allen wrote. “How did he know The Alphabet issued their indictment and I could face imprisonment of up to 40 years? How did he know I planned to shoot myself in the head when the team got back to Boston? How did he know?”

Allen isn’t looking for pity, wouldn’t accept it if offered. He betrayed his school and his basketball program and will pay a steep price for that forever. But if you want to see a person asking hard questions of himself while painting the landscape around his actions, this might be the book for you. There’s more to the story. A Philadelphia basketball story, but much more.