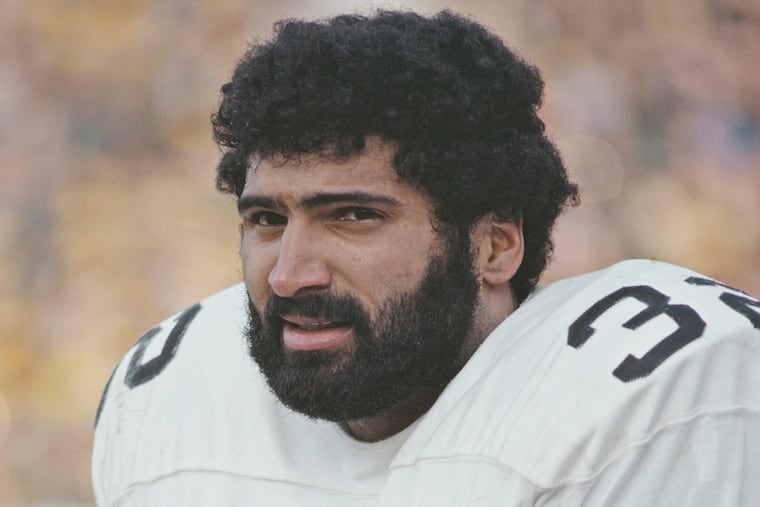

Franco Harris was more than a Steelers icon. He was a cultural touchstone.

He grew up in Mount Holly, went to Penn State, and became one of the most recognizable figures in one of the most memorable dynasties in sports history.

The March 28, 1968, edition of the Camden Courier-Post carried, on page 38, a seven-paragraph story of some local interest, though it didn’t promise much more than that. Franco Harris, who lived in Mount Holly and was the star fullback at Rancocas Valley Regional High School, had decided that he would attend Penn State and play football there for Joe Paterno.

“It offers a fine course in hotel management,” Harris said in the article, “and … I think Coach Paterno is a great guy.”

It was impossible to know then, of course, what was to come for Harris in the years after that news item was published: that, upon his death Wednesday at 72, he would have become one of the most recognizable figures of one of the greatest dynasties in sports history, the “Steel Curtain” Pittsburgh Steelers, who won 77% of their games from 1972 through 1979, including four Super Bowls in a six-year period. That he would be the first Black man to be selected as the most valuable player in any Super Bowl. That he would rush for 12,120 yards in his 14-year NFL career, which culminated in his induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame in 1990. That the son of Cadillac Harris and Gina Parenti — the former a supply sergeant who served in Italy during World War II, the latter a native of Pietrasanta who escaped the Nazis’ slaughter — would be immortalized in America’s collective memory for his central role in the most famous play in its most popular sport: “The Immaculate Reception,” his 60-yard touchdown catch on the final play of the Steelers’ 13-7 victory over the Oakland Raiders in the 1972 AFC playoffs.

“I was blessed with certain talents, and I tried to use those talents to the best of my abilities,” Harris said during his Hall of Fame acceptance speech. “How can I help my team? Can they count on me when it was needed?”

» READ MORE: Jalen Hurts’ injury has some Eagles followers freaking out. Is it really time to panic?

Before growing into a 6-foot-2, 230-pound running back with the Steelers, Harris earned money as a kid by learning how to spit-shine shoes at Fort Dix, where his father worked. His Mount Holly neighborhood was as racially mixed as his heritage, though his upbringing was not without its tension and discomforts. One day, Harris was walking along a Jersey boardwalk when an old man, seemingly homeless, his face twisted and craggy, asked him for a cup of coffee. Harris bought him one. The old man eyeballed him, then said: You’ve got a Roman nose. You’ve got Roman eyebrows. You’ve got a Roman face. But you’re Black. I don’t understand.

“Harris felt no need to explain and walked off,” author Gary Pomerantz wrote in his book Their Life’s Work: The Brotherhood of the 1970s Pittsburgh Steelers, “knowing the old man had simply said what others thought.”

At Penn State, Harris rushed for 2,002 yards over three seasons under Paterno. The Steelers made him their first-round draft pick in 1972, and he was named the NFL’s offensive rookie of the year for his 1,055 rushing yards and 10 touchdowns, earning the devotion of a particular subsection of the team’s fan base. The members of “Franco’s Italian Army” became fixtures at Three Rivers Stadium, donning World War II helmet liners and chowing down on chicken parmigiana, prosciutto, and other delicacies. Myron Cope, the Steelers’ radio play-by-play voice, even recruited Frank Sinatra to join the group.

The Immaculate Reception was Harris’ tour de force, however, combining headiness, instinct, and athleticism into a single miraculous sequence. Go ahead. Cue up the replay. When the Steelers’ John Fuqua and the Raiders’ Jack Tatum collide, the ball caroms off them in the same instant, and it rebounds with such distance that it disappears from the TV cameras’ wide-angle shot. The viewer loses sight of it until there, emerging from the right side of the screen, is Harris, sprinting past the stunned Oakland players toward the end zone, the ball tucked under his left arm. Did it touch the ground first? Did he really catch it? That lasting element of mystery, so rare in our modern age of ubiquitous technology, is what makes the play special.

“Right place, right time,” Harris told a TV reporter after the game, “with a little bit of luck.”

The Immaculate Reception was more than merely the starter’s pistol shot for the Steelers’ run of dominance. Like the 1958 NFL championship game before it, like “The Catch” by Dwight Clark in the January 1982 NFC championship game after it, the play helped to elevate professional football to the country’s true national pastime, vaulting the sport to a place of cultural relevance that it still occupies today and that few institutions, if any, approach.

A traveler who flies into Pittsburgh International Airport is greeted by two life-sized statues. One is of Harris in mid-Reception, reaching down to scoop up the ball. The other is of George Washington. My maternal grandmother, off-the-boat Irish, grew to love football, watching games every Sunday with my grandfather in their rowhouse in Olney, joined by their family and friends. Harris was her favorite player.

The thing was, part of the reason she adored him was that, for the longest time, she thought his name was Frank O’Harris. True story, and no matter: Her appreciation for him remained unbroken and unconditional. She wasn’t the only one.