The greatest play in St. Joe’s history helped inspire the term ‘March Madness’ 40 years ago | Mike Jensen

Without John Smith's famous winning shot, maybe the term March Madness does not exist today; a phrase was born that 1981 day to describe a string of crazy NCAA Tournament upsets.

Thinking about roads not taken, doors in your life that won’t open if not for a specific instance of luck. Maybe a wife you never meet, children never born … it can be breathtaking. John Smith has a sports version of that. If one man doesn’t walk in off Market Street to watch a basketball game between a local two-year college and Drexel’s junior varsity, then the greatest play in St. Joseph’s University basketball history can’t happen.

No Fourth and Shunk layup?

“If Frank Blatcher doesn’t walk in that door, you and I are not having this conversation,” Smith said over the phone from his home at the Jersey Shore.

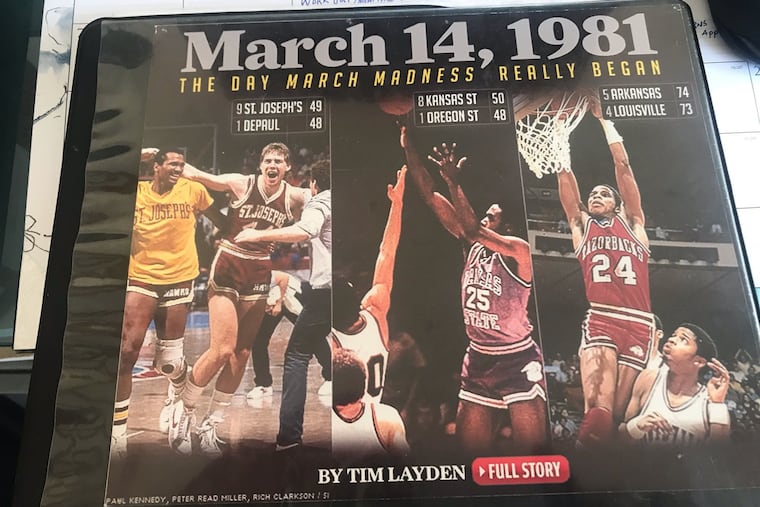

He wouldn’t have been in Dayton, 40 years ago, March 14, 1981, second round of the NCAA Tournament, when a pass showed up from Lonnie McFarlan. It was Smith who was wide open under the basket, nothing but the buzzer to beat … as the Hawks knocked off DePaul, the No. 1 team in the nation.

» READ MORE: Steve Donahue on Penn's basketball season that wasn't.

Without that play, maybe the term March Madness does not exist today, since the phrase was born that day in 1981 to describe a string of crazy NCAA Tournament upsets that was topped by St. Joe’s doing its thing, coached by Jim Lynam.

For Smith to be a part of it, it took Lynam, not yet the Hawks coach, walking in the door at Drexel, his American University team about to play Drexel. There was a preliminary game, Drexel JV against Penn State-Ogontz. Blatcher was there for that one, to see his guy John Smith.

Lynam spotting Blatcher in the gym was worth a conversation. If you go back far enough, you understand Blatcher was Philly hoops royalty.

From his obituary when Blatcher died in 2019 at age 90: “Behind star Tom Gola, the [1954] Explorers beat Bradley, 92-74, to win their only NCAA championship. Mr. Blatcher was a starter for the team but could not attend practice before the national semifinal and final because of the death of his father. Nevertheless, he led his team in scoring in both rounds while coming off the bench, totaling 42 points in the two games.”

“Frank is someone I would consider a casual friend,” Lynam said. “I knew Frank better than Frank thought I did.”

Meaning, Lynam knew Blatcher’s accomplishments at La Salle.

“I was ready to listen despite the fact that I didn’t have a clue who John Smith was,” Lynam said. “I was incredulous a bit. For Frank to describe him. He said, ‘You’re going to like this guy.’ "

This all comes up if you ask Smith if there was a story about how he got to St. Joe’s.

“It’s a long one,” Smith said.

Blatcher had been his summer league game coach after Smith had played at St. John Neumann.

“I wasn’t a star player, second-team all-Catholic,” Smith said. “I came into my own during that summer.”

The competition included all the top competition in Philly and he went from scoring 13 a game in high school to 30 a game in the summer.

“A powerful 60 days of me coming out of my shell,” Smith said.

His scholarship opportunities at that point? None. Frank Blatcher made a phone call, not to Lynam, but to another friend who made another phone call. Suddenly, an offer came from Fairleigh Dickinson.

“They gave me a scholarship without ever seeing me play,” Smith said.

How did that work out?

“I literally left three days in, the middle of the night, while my roommates were sleeping,” Smith said.

Smith had grown up on Second Street between Ritner and Porter … “born and raised Two Streeter,” Smith said.

He had developed a smell detector and none of what he found up in Teaneck smelled quite right. It wasn’t simple homesickness, Smith said, even though North Jersey “to me was like going to France or somewhere. The farthest we went was North Wildwood.”

What was the problem?

“It wasn’t right for the moment I showed up,” Smith said. “They didn’t know who I was. ‘We have no record of you.’ "

» READ MORE: Collin Gillespie's decision.

They told him to call the coach, who was out of town.

“It took hours to get it turned around, to get a key, to get into the dorm,” Smith said.

The dorm, in his memory, was just for basketball players. They told him to get in a first floor room. He arranged all his stuff. Then, never mind, go up a floor. All right, do it all again. Meantime, he said, dorm life made Animal House seem a hundred times tamer. Still, no coach.

“You don’t feel wanted,” Smith said.

He remembers calling home in the middle of the night, talking to his dad. At the time, his mom worked a 4-to-12 shift. He told his dad, “Listen, this ain’t for me.’ My dad is trying to talk me out of it, saying, ‘Hey, it’s free. You just got there.’ "

Smith told his dad that if he didn’t hear their car horn beep that night, he’d find a bus the next day

“Two-thirty in the morning, I heard BEEP BEEP.”

He was 18, but knew what he was giving up. “You’re planning your next move,” he said.

That turned out to be another phone call, to a different friend, who called the coach at Penn State Ogontz, now Penn State Abington. “I’m back on the market,” Smith said.

Ogontz was a two-year program. Smith played one, scored 725 points. It’s not unusual for a coach to be in a gym early watching some preliminary game. It is unusual for the coach to care about what he’s watching. Lynam knew Blatcher and Blatcher talked up Smith and Smith clearly had some skills out there. Smith started hearing from American University.

Then Lynam switched schools, back to his own alma mater on Hawk Hill, and Smith remembers getting a call. St. Joe’s?

“I only had one offer,” Smith said. “It was either American, or go work on the waterfront with all my buddies.”

Lynam said he picked Smith up in a Volkswagen Beetle for his recruiting trip, his own son and a friend in the backseat, Smith wearing shorts and a sleeveless T-shirt for the big visit. He was back from campus 2½ hours later.

“John Smith was tough, period,” Lynam said. “You can say South Philly — fine. When you’re a tough guy and you’re from the coal region, they’ll say it’s because you’re from the coal region. From South Philly, it’s because you’re from South Philly. I don’t know about that. But John Smith, he was tough.”

Smith provided the Hawks more than just a layup. A 6-foot-5 forward, as a senior captain, he averaged 10.8 points, 6.4 rebounds and 2.5 assists. He’d scored 20 points in the NCAA first-round win over Creighton to help the Hawks get to DePaul.

Also, if you think this group was in awe … that’s not really a Fourth and Shunk deal either. (Fourth and Shunk, home of the Murphy rec center, where Smith spent his youth.) Mark Aguirre was a star for DePaul.

“I waited until the game got down to the real nitty-gritty,” Smith said right after the game. “Then I told him, ‘Hey, pal, it’s our ballgame.’ I knew the tide was turning. I could feel the momentum shift. Our enthusiasm was taking over.”

Lynam can still remember Smith stealing the tap on a crucial late-game jump ball from DePaul’s center who had more than a few inches on him.

“I call it the South Philly Quick Off the Floor,’ " Lynam said of that one.

The whole thing is part of the lore of the sport. Right afterward, Lynam hugging his daughter Dei. Aguirre walking right off the court with the ball, walking outside still in uniform, throwing the ball in the Miami River.

Smith hasn’t tried to live off the memories all these years, he said, but they’ve been along for the ride. Smith has always worked in financial sales. He doesn’t bring it up with clients, he said. But his boss once started a Power Point with it, and certainly plenty of people have done the, “Hey, you aren’t …”

That last play …

“It was absolutely one thousand percent a function of preparation,” Smith said. “There’s no other way to describe it.”

DePaul’s Skip Dillard missed at the foul line. Hawks down one. No timeout needed.

“If he missed, we were going to run our fastbreak offense,” Smith said. “We did it every day. It wasn’t just a one-off. It was repetitive.”

Meaning, everyone knew what lane to run in. Same as in practice. The heavy lifting was done by Bryan Warrick getting the ball up court, dribbling past human obstacles.

“Over a hundred years, there have been some pretty doggone good guards at St. Joe’s, too many to name,” Smith said. “But what Bryan Warrick did, shaking and baking — I’ll put that up there with any guard in St. Joe’s history.”

The ball to McFarlan in the corner. To a man, the Hawks love to joke that the only surprise was that McFarlan didn’t shoot.

“We kid, we all kid, that Lonnie never met a shot that he didn’t fall in love with,” Smith said. “But Lonnie was a high school all-American. He and Tony Costner, they could have gone anywhere. He was an all-around stud. He did a whole lot more than shoot.”

That time, he passed. Smith’s “Fourth and Shunk number,” as he immediately labeled it postgame, went up with three seconds left.

“It’s one of those things, one of those events, people will tell me where they were,” Smith said, remembering a friend from the neighborhood who became a Marine, watched that game in a tent in Okinawa, screaming “That’s my guy.”

The whole path to that layup — there’s no bus for that route. Lynam clearly remembers it was Blatcher who spoke up for Smith. He just didn’t remember where the conversation took place, at Drexel. Why would he? Lynam’s life didn’t change so dramatically that day, although if you think about all the roads taken later on, maybe it did. Without Smith, is there a DePaul game? Maybe Lynam stays at St. Joe’s and coaches for 20 years instead of moving on to the NBA?

These men just know one thing, the road chosen, nobody forgot it, even 40 years later.