Ebony’s archives have been sold. It’s just one more reason why we need to stop taking our beloved institutions for granted | Elizabeth Wellington

Ten years ago, I went down to my parent’s basement in search of an Ebony from the 1970s with my beloved Jackson 5 on the cover. But when I made it to the shelf where mom kept the 11x14 glossies from the late 1960s and early 1970s, they were gone.

Ten years ago, I went down to my parent’s basement in search of an Ebony from the 1970s with my beloved Jackson 5 on the cover. But when I made it to the shelf where mom kept the glossies from the late 1960s and early 1970s, they were gone.

Turned out my dad, during one of his chuck-everything-in-sight clean-a-thons, tossed them.

Perhaps he was over the clutter. Perhaps he wanted to open his freezer without the tattered periodicals crashing down on his head. He never explained. What I do know is the endless boxes of chipped china and broken blenders lived through the haphazard purge.

Yet those Ebony magazines, jam-packed with the history of my favorite black superstars, were trashed because ultimately my dad didn’t see the value in them.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the value we place on our precious people, places, and institutions as things I always thought would be with me — Soul Train on Saturday mornings, the Catholic Church, my idea of what it means to be American or my favorite shopping haunts — are simply ceasing to exist. With their disappearance comes what feels like violent endings to a precious eras. What used to define me is — poof — gone.

Late last month, after years of years of financial struggle, Johnson Publishing Co. sold its precious photo archives for $30 million to a consortium of foundations that collectively promised to donate them to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture and other institutions. That archive consists of four million pictures and countless photos of celebrities from Lena Horne to Duke Ellington, athletes from Muhammad Ali to Satchel Paige, and politicians from Jesse Jackson to President Barack Obama. Among the most iconic is a 1968 photo of Coretta Scott King, grieving at the funeral of her husband, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. That image earned Moneta Sleet Jr. the distinction of becoming the first black person to win a Pulitzer Prize for photography.

It’s not lost on me that in the same week of the Jet/Ebony archive sale, Philadelphia’s black community lost one of its most cherished photographers, Robert Mendelsohn, who was found dead in his Germantown rooming house on the evening of July 28.

Mendelsohn, who was white and Jewish, spent decades shooting photos of Philadelphia high society for black publications. He went to events that outfits like Getty, the Associated Press, or, for that matter, The Philadelphia Inquirer would not and did not send photographers to. He died alone during one of the hottest weeks of the year in a room without air conditioning.

Did we value him?

I’m still having a tough time wrapping my head around the fact that the former South Street home of the First African Baptist Church is now a boutique hotel called the Deacon. The more-than-100-year-old building is where black people worshiped and politically organized in the early part of the 20th century. Here Booker T. Washington and W.E.B Du Bois spoke to black congregations about the fight for equality. Now it’s a boutique hotel.

Sigh.

Trust me, I understand that the only constant is change. And that historically black institutions aren’t the only ones that are disappearing. Last week, the Archdiocese of Philadelphia put three more neighborhood churches on the chopping block because parishes can’t afford the upkeep.

We know that favorite retail institutions remain in crisis. The latest victim: 96-year-old Barneys New York, which on Tuesday announced it was filing for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, closing stores in Chicago, Las Vegas, and Seattle. While Philly was not on the list of affected stores, I’d be surprised if the lease on the Walnut Street Barneys was renewed.

But there is something about the demise of historically black institutions that makes these ends even sadder. These institutions that served black people were there for us when no one else was. If it wasn’t for the entrepreneurship and savvy of founder John H. Johnson, these photos would never have existed. So pardon me if it makes me sad that we are now relying on the benevolence of well-meaning foundations to save what we should have valued more in the first place.

Johnson, who was born in Arkansas in 1918, launched Ebony in 1945 as a sort of Life magazine for black people, to counterbalance the tales of poverty, crime, and woe that the then-mainstream media told and retold about the black community. Johnson wanted people ― especially other black folks — to understand that black people were human beings who held down jobs, owned businesses, and lived good lives. He launched sister publication Jet in 1951.

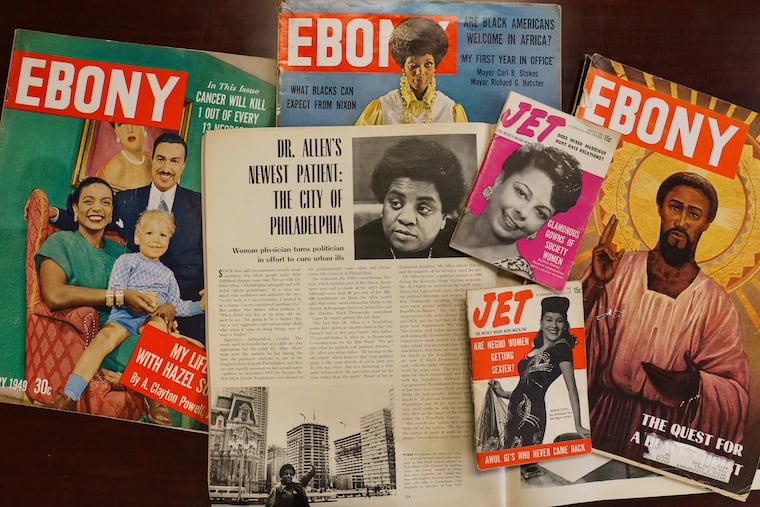

Both became a staple in black homes, black beauty salons, black barbershops. Anywhere black people congregated — especially my grandmother’s house — there was an Ebony or Jet magazine.

“What Johnson did was an Amazing Grace,” said Charles L. Blockson, who collected nearly every edition of Ebony and Jet magazines the publications’ nearly 70-year runs. They’re now part of his eponymous collection, housed at Temple University’s Sullivan Hall. “We are talking about the history of our race. [Johnson’s] eye was always on the positive. It was the pride of so many black families.”

Ebony and Jet still live on online, but they do little more than act as landing pages for celebrity tea. Gone are the stories about people like the late South Philadelphian Richard Robert Wright Sr., a former slave who enrolled in the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School when he was in his 60s and founded Citizens and Southern Bank and Trust Company in 1921.

His story was featured in the first Ebony magazine back in November 1945. I spent the better part of Monday afternoon thumbing through these treasures. I read articles about Adam Clayton Powell, who, legend has it, baptized my grandfather in Harlem’s Abyssinian Baptist Church, and his wife, jazz singer Hazel Scott. And I read a story about a Philadelphia doctor-turned-Republican city councilwoman, Ethel D. Allen. The article was printed in the 1970s, as she was just gaining steam.

While I was taking this black-and-white stroll through great moments in black history, it came to me: Not only did my dad not value Ebony, I didn’t, either. Did I ever have a subscription? No. Did I buy it off the newsstands? Rarely.

It’s well-documented that after Johnson died in 2005, Johnson Publications had money problems. Industry insiders questioned the leadership of Johnson’s daughter, Linda Johnson Rice, and many writers who freelanced for Ebony (myself included, although I only wrote a couple of pieces) were not paid on time for their work. But there’s blame to share.

“The only reason it would be there is if it was supported by you, not your mama, not your daddy, but you," said Bryan Monroe, an associate professor of journalism at Temple and former vice president and editorial director for Johnson Publishing for Ebony and Jet. Monroe’s office was once outside the photo archive and he fondly remembered browsing through photographs of B.B. King or Sammy Davis Jr. “When you stopped buying the magazine or stopped subscribing to Ebony and Jet to your home, you effectively killed it. If two million people would have kept subscribing, those archives would be flourishing today.”

And so I sat there leafing through these magazines, because I didn’t know when I’d ever get a chance to come back. And I wasn’t tempted to scroll through my Instagram even once.

.